What does it mean to control interest rates?

Let’s start with an easier question. In what sense does OPEC control oil prices?

Imagine that OPEC produces 40% of the world’s oil. The cartel also has substantial excess capacity. Now let’s think about its control of global oil prices.

Because both the demand for oil and the supply of non-OPEC oil are relatively inelastic in the short run, OPEC has the ability to double global oil prices, or cut them in half, almost overnight. That’s a lot of control. So let’s assume that OPEC targets global oil prices at $100/barrel, and adjusts output to make the price stick.

There is one problem with this policy; oil supply and demand become far more elastic in the long run. So now let’s assume that the $100 oil price causes a fracking revolution, and non-OPEC supply rises sharply. To keep the price at $100/barrel, OPEC must reduce output to 35% of global production, then to 30%, then to 25%, etc., etc. They can do this for a while, but it’s painful.

OPEC also worries about the long run viability of the oil market, so eventually it decides that it’s no longer wise to keep the price at $100, even though in a technical sense it could continue doing so up until the point where its output fell to zero. OPEC decides that it is in their long run interest to face reality, and allow the fracking boom to reduce oil prices. There are two ways of making this happen

1. OPEC could stop controlling oil prices. They could instruct their members to produce a total of 40 million barrels per day, and let the market set the price.

2. They could keep controlling the price, but gradually reduce the price as needed to keep output at close to 40 million barrels per day (as fracking output rises). Thus they might reduce the price to $95 for a couple months, and then later to $90, and after another 3 months down to $85, etc. Prices would fall in a sort of step function, eventually hitting $45 after a few years. At each step of the way, price would be set at a level expected to keep OPEC output pretty stable, but once at that new price, output would be tweaked each day as needed to keep the price stable. Then after a few more months, another $5 price cut.

So in case #1 OPEC is not controlling global oil prices and in case #2 OPEC is controlling oil prices. But the two cases are actually pretty similar, and as you make the price adjustments smaller, the two cases get even more similar. Thus you could imagine the price being adjusted by $1 at a time, not $5, and the adjustments occurring much more frequently.

At what point do you move from a scenario where OPEC is controlling the global oil price to one where the market is controlling the global oil price?

Now let’s go back and think about the fracking boom, described earlier. Suppose OPEC actually responded to the fracking boom with the step function approach to lowering prices, described in case #2. So for periods of several months at a time, the price would be fixed by OPEC, then a sudden drop of $5/barrel. How would you think about this multi-year price decline, from $100 to $45? Does it make more sense to talk about the fracking boom causing a huge plunge in oil prices? Or should we say that OPEC caused a huge plunge in oil prices?

1. On the one hand, you could argue that OPEC controlled oil prices all through this period, and hence they caused the decline. They made the periodic adjustments in the official price, and all the time they had the ability to set world prices in a different position.

2. On the other hand, the fracking boom was the big disruptive force in the global marketplace. As fracked oil output soared, it caused global prices to fall. OPEC could have offset that, at least for a while, but they chose not to, keeping OPEC output close to 40 million barrels per day. OPEC did not take concrete steps to prop up oil prices.

Because terms like ‘cause’ are not well defined, there is no right answer. But in this case I think I’d prefer to say that the fracking boom caused the oil price plunge. And I don’t think it’s just me; many economic pundits would view that as a plausible way of describing what caused the big plunge in oil prices.

It turns out that this example is uncannily similar to the plunge in interest rates from July 2007 to May 2008. Before going over that example, recall an important aspect of the previous example. I said that while in the short run OPEC could have continued holding oil prices up at $100 for an even longer period, they also had long term objectives to think about, which made them conclude that it was wise to allow some price decline, so that their long term hold on the oil market would not be completely lost.

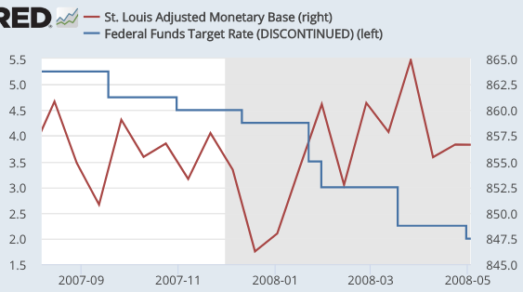

Now think about the Fed during 2007-08. Real estate is declining sharply, and there are many fewer mortgages being issued. The lower demand for credit puts downward pressure on interest rates. For the Fed to prevent interest rates from falling, they’d have to continually reduce the monetary base. That sort of tight money would keep rates from falling below 5.25% (via the liquidity effect).

But the Fed realizes that if it did what it took to prevent rates from falling, then this policy would disrupt its long run goals for the economy. Big time! So instead of reducing the monetary base it decides to allow interest rates to fall, while holding the base fairly stable. There are two ways it could do that:

1. It could hold the base roughly stable at $855 billion (plus or minus 1%), and completely stop targeting interest rates. Let the market set interest rates.

2. It could instruct the New York Fed to reduce rates by ¼% or ½% every few months, as needed to keep the base fairly stable. On days when the official fed funds target was not being adjusted, the New York Fed would hold rates stable with small adjustments in the base, up and down.

You could also envision intermediate cases, like the official fed funds rate target being adjusted in 5 basis point steps, instead of 25 basis point steps. The smaller the adjustments, the more it would look like the market was setting the rate at a level that resulted in a stable monetary base.

I would argue that case #1 and case #2 are actually pretty similar. But in case one it looks like the market is setting interest rates, and in case two it looks like the Fed is controlling interest rates.

Now let’s return to the weak credit markets, caused by the housing depression. Does it make more sense to talk about weak credit markets depressing interest rates? Or should we say the Fed caused interest rates to fall during 2007-08? And if the latter, exactly how did the Fed cause interest rates to fall? After all, they did not increase the monetary base, which is their usual way of causing interest rates to fall. (This is pre-IOR).

Opinions will differ, but I think it’s more useful to talk about weak credit markets causing a decline in interest rates, and the Fed just sort of getting out in front of the parade by adjusting its official target as the “natural rate of interest” fell during 2007-08. But since the Fed always has the technical ability to move the actual interest rate away from the natural rate, at least for a period of time, others will prefer to say that the Fed caused interest rates to decline. I would not strongly object to that claim. Still, it is interesting that while other pundits would agree with me on the fracking boom example, they’d probably disagree here, insisting it was the Fed that cut rates.

What I would strongly object to is the claim that the Fed caused interest rates to fall during 2007-08 with an easy money policy. I defy anyone to come up with a coherent definition of easy money, which would imply that money was easy during 2007-08 (when nominal rates fell), and also easy during the second half of 2008 (when real rates soared), and was also tight during the Argentine hyperinflation of the 1980s (when the base soared).

I recently gave a talk at Kenyon College, and this post (along with another at Econlog) was motivated by a discussion with Will Luther. He directed me to an earlier post of his:

I was pleased to see David Henderson call out Bill Poole for claiming the Fed sets the federal funds rate. It doesn’t, of course. Welcome to the Wicksell Club, David! We don’t have ties or t-shirts. But our common cause is worthwhile.

Many of my economist friends get annoyed when I insist they refer to setting the federal funds rate target (as opposed to setting the federal funds rate). They know that the Fed is not literally setting the federal funds rate; that the rate is determined by suppliers and demanders in the overnight market; and that the Fed, as Bernanke has made clear, has a limited influence on even short term rates. But, they maintain, it is a convenient shorthand of little consequence.

I disagree. Perhaps I have spent too much time in a liberal arts environment, but I believe the language we use matters. In this case, the dominant Fed-sets-rate language makes it easy to assume that the federal funds rate is low because the Fed’s target is low. It makes it difficult to even consider the possibility that the Fed’s target is low because the market-clearing federal funds rate is low. Moreover, it suggests the Fed is in a direct and dominant position when, in fact, the Fed plays an indirect role and, at least by my assessment, is subservient to routine market forces. It also seems to perpetuate the all-too-common error of associating low rates with expansionary monetary policy and high rates with contractionary monetary policy. (Scott Sumner is right: Interest rates are not a reliable indicator of monetary policy.)

The Mercatus Center is a good resource for papers that discuss this issue. Check out Jeffrey Hummel’s paper. A somewhat related paper by Thomas Raffinot is also useful.

Tags:

25. March 2018 at 18:02

I think in terms of the yield curve. The focus should always be on new money creation, not interest rates. That said, a competent monetary response in’08 would’ve had short nominal rates going lower, faster, and longer rates rising, until it was safe to start raising short rates too, by selling T-bills, for example.

The Fed did too little, too late, and muddied the waters for many non-market monetarism’s, by buying things like MBS assets and longer-term treasuries. Operation twist, for example, created much confusion as people then argued whether a healthy response entailed long rates moving up or down.

25. March 2018 at 18:08

I guess I should expand by saying that it seems to many that the Fed uses interest rates as a signal while targeting inflation and unemployment. The Fed not only caused more confusion than necessary in their rate signaling, but also with regard to their inflation and unemployment targets. The fact that there is a dual mandate causes inflation. The whole structure of how they attempt to stabilize prices is messy, with large occasional errors seemingly inevitable, in addition to all the problems you’ve pointed out over the years.

25. March 2018 at 18:11

That should have read, the fact that there is a dual mandate causes confusion.

Couple all the above with pretty consistent failures to hit the inflation target, controversy over the ZLB, and arguments over the NAIRU, and you have the mess we witnessed over the past 10 years.

25. March 2018 at 23:34

Excellent blogging.

And a reminder that the Fed never does nothing. Rather, the Fed is always like a baseball manager watching his struggling starting pitcher.

The manager can do nothing—leave the pitcher in—but that is not doing nothing.

26. March 2018 at 05:38

Excellent post. I fear most people won’t understand.

26. March 2018 at 10:20

‘Control’ is a very slippery term. I suggest that “A is controlling B,” where A is a purposive agent and B is some magnitude or other, means that A is accurately noting B’s current value (the time-lag, if any, being very slight); that A is capable of acting so that B will take on whatever (or almost whatever: see below) value A might wish (the time lag being specified, perhaps only contextually); that A knows how his different possible actions will affect the value of B; that the value of B is an overriding concern of A’s, in the sense that A’s actions determine B’s value not as a side-effect, where A is aiming at some other objective that overrides his concern about B’s value, but rather as an end in itself or as a means to A’s ultimate end; and that if there are some possible values of B that A could not produce–if A’s different possible actions would not cover setting B’s value over its full range–those values inaccessible to A form a relatively small or unimportant subset of the possible value–that most of the possible values, or most of the important possible values, are within the range determinable by A.

I doubt that Fed influence over any interest rate covers a wide enough range to count as “control” simpliciter. For example, I think today’s 3-month T-bill rate is about 1.7%. How high or how low could the Fed drive that rate in the next five seconds? In the next five minutes? In the next 24 hours? The answers, whatever they are, will (I suspect) show a rather narrow range (the shorter time-frames being the narrower), amidst the full range of possibilities, which is something like minus 2% to plus infinity. Even if I’m wrong about this, the claim that the Fed controls “interest rates” is objectionably vague: vague as to maturity, vague as to the time-frame (interest rates five seconds from now, interest rates a year from now, etc.), etc. Probably the actions that would set one of these rates would leave the Fed no freedom to adjust the others, which would instead be determined by market forces. If the Fed is focused on, say, the Fed Funds rate (overnight), then it is not controlling, but merely influencing, all other interest rates (so it does not after all control interest rates [plural]).

It might also seem plausible to reject the claim of Fed “control” of (say) tonight’s Fed Funds rate on the grounds that the Fed has objectives which might override any concern it had about this rate, in which case its actions–which did in fact determine this rate–would be aimed at some other objective that the Fed considered overwhelmingly important. (Then by my definition it would not be “controlling” the Fed Funds rate.) But I disagree, because it seems that the Fed regards its control of the Fed Funds rate as causally efficacious in producing whatever results it is aiming at. Now, in the typical case in which A controls B, A exercises this control in the service of some other objective, regarding the value of B as of merely instrumental importance for achieving that other inherent end. And that seems to be what is happening with the Fed: it sets the Fed Funds rate where it does because it thinks this will produce some combination of “stable prices” and “full employment” and, perhaps, some further objective that it has not articulated. Even if the Fed is mistaken about the efficacy of setting the Fed Funds rate, we have here no grounds for denying Fed “control.”

26. March 2018 at 10:21

By the way, great post!

26. March 2018 at 12:37

Early in his presser last week Powell sated that the FFR defines the stance of mon pol!

26. March 2018 at 15:24

Forgive me if I’m asking a stupid question, but isn’t this just a case of the Fed setting the ceiling and floor via the discount rate and interest on reserves? If you set both these things that’s de facto control, is it not? Similar to an accounting concept of displaying assets on the balance sheet in the case of direct control, despite no legal ownership of an asset.

26. March 2018 at 15:48

Philo, Just to be clear, I am not claiming that the Fed is unable to move rates by a lot in the very short run.

Jeff, No, I’m looking at the period before IOR. But even if IOR had existed, it would not change my argument about 2007-08. As far as the rest of your comment, I think you missed the point. Take another look at the oil example, and see what you think about that case.

26. March 2018 at 15:57

Marcus, I’d say he claimed that it influenced the stance of monetary policy, if I read it correctly. Not sure he thinks it defines the stance.

27. March 2018 at 02:51

Scott,

The way I look at is.

1. I don’t distinguish between the Fed and the rest of the banking system….although the Fed exercises control over the other parts of the banking system.

2. What happens entirely within the banking system (e.g. exchanges between the Fed and commercial banks) doesn’t matter.

2. What does matter is the action of the banking system exchanging (buying or selling) financial assets (or money if you want to look at it that way) with the non-banking sector (private sector and the government.)

3. Everything else is a result of that action or the expectation of that action.

27. March 2018 at 05:33

When economists finally figure out what to look at, and where to look for, then they can discuss tight and easy money.

27. March 2018 at 05:38

The last half of 2008 was exactly the same as the first half of early 1980. It’s all about my monetary fulcrum.

–Michel de Nostredame

27. March 2018 at 08:40

dtoh, I find it most helpful to completely ignore the banking system when thinking about monetary policy in 2007. Back in those days, 95% of the new money created went out into the economy, only about 5% was held by banks. They were not a major factor in the transmission mechanism.

27. March 2018 at 10:51

Scott,

Yes, but hasn’t that changed now with the advent of IOR and the massive increase in ER. I think you have to net that out to see the actual impact on the real economy.

28. March 2018 at 07:27

The range of the Fed’s influence on interest rates varies across the various interest rates, as well as on the specified time lag. How much, up or down, do you think the Fed could move, say, the 3-month T-bill rate in the next five minutes? How much *in the next day*? Etc.

Note also that the Fed’s power is limited by the fact that everyone knows that if the Fed did what was widely perceived to be a terrible job *it would be abolished*.

28. March 2018 at 19:26

dtoh, I still don’t see the credit channel as being important. But obviously banks now demand a much bigger share of base money. I wish they’d end the IOR program.

Philo, I agree.

28. March 2018 at 21:36

Scott,

Let’s forget about the “credit channel” and just talk about the action of the banking sector (Fed plus commercial banks) exchanging financial assets for base money with the non-banking sector.

We might argue about causality, but I think we’d agree that we are talking about the same action (i.e. this exchange) as being the transmission mechanism for monetary policy (along with expectations regarding that action.)

Further, I think we would both agree that exchanges wholly within the banking sector (such as Chase exchanging Treasures for ER with the NY Fed) is not effective as a transmission mechanism (except possibly through expectations as to what the market thinks the Fed may or may not do with the IOR rate in the future.)

29. March 2018 at 01:45

OT but Japan running big national budget deficits…still.

Japan govt lays groundwork for more stimulus spending to offset tax hike

Reuters Staff

2 MIN READ

TOKYO, March 29 (Reuters) – Japan’s government began laying the groundwork on Thursday for big spending next year to offset the impact of a planned nationwide sales tax hike.

The government should manage fiscal policy to prevent growth from collapsing and should keep the impact of past sales tax hikes in mind when it compiles the fiscal 2019 budget, a mid-term report presented at the government’s top advisory panel showed.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s cabinet is likely to adopt the report’s advice on fiscal policy, setting the stage for another year of big spending that many policymakers say is needed to prevent growth from slowing.

29. March 2018 at 08:46

Scott,

the 30-year Treasury currently yields about 3% exactly, pretty much the same as it was in December of 2005 when the Fed started its tightening cycle. The yield curve is pretty damn flat right now. I fear further short-term rate hikes could create an “own goal” here. Thoughts?

29. March 2018 at 08:56

dtoh, In my view the transmission mechanism is the hot potato effect for base money. It’s not about what base money is exchanged for, it’s about the supply and demand for base money.

Ben, That article says nothing about boosting the deficit.

Brian, No, the yield was 5% back then.

29. March 2018 at 09:49

Scott,

My bad- I meant December of 2015 when the Fed started its tightening cycle…

29. March 2018 at 13:47

OPEC is not a price-setter. It is a revenue maximizer.

If demand is growing faster than non-OPEC supply can respond, then OPEC has an incentive to allow the price to rise and add modest volumes, but not enough to materially reduce prices.

If non-OPEC supply is capable of growing faster than global demand, then in the short term, OPEC has an incentive to add supply in the scramble for immediate revenues, which has the effect of further depressing prices and revenues.

When OPEC is able to bring government spending in line with reduced oil revenues, OPEC will then refrain from further depressing prices and will allow non-OPEC supply to set marginal cost and OPEC will add marginal volumes around that level.

That’s pretty much the story since 2005, leaving out the crisis period of late 2008 to mid-2010.

29. March 2018 at 14:39

Brian, I’m not too concerned about rate hikes here, although I’d probably hike them more slowly than the Fed intends to.

Steven, You said:

“OPEC is not a price-setter.”

That’s fine, but that has no bearing on this post, which deals with hypotheticals.

29. March 2018 at 15:18

Scott,

If you ignore increases in ER, there is no increase in base money without the purchase of assets from the non-banking sector. It’s like ying and yang….. one can not happen without the other happening.

I think where we differ is that you believe the injection of money is an independent phenomena, which then causes people to spend more. My view is that the exchange of assets for money happens as a result of people having been induced to spend more because of lower rates or expectations of higher NGDP, and that they therefore sell assets (e.g. borrow more) in order to obtain the money needed for that higher spending. Without this desire to spend more all the base money created through OMP would simply end up as ER.

30. March 2018 at 00:27

Why interfere with interest rates at all? The GDP maximising rate of interest is presumably the free market rate, so leave it alone.

Trying to adjust demand by fiddling with the price of money makes as much sense as adjusting demand by fiddling with the price of steel – which would, no question, be an effective way of adjusting demand.

That of course leaves the question as to how to impart stimulus. Well that can be done by having the state print money and spend it (and/or cut taxes) as suggested by Bernanke.

30. March 2018 at 09:10

Excellent post. I think there’s an important difference between the Fed and OPEC. The Fed has total control over the supply of US dollars, whereas OPEC does not have control over the oil supply.

Given this total control, the Fed has 100% control over any one price. That could be gold, silver, 3 month US bonds, one year CPI futures, 5 year NGDP futures, or whatever. It could temporarily control two prices, but not permanently.

This is exactly what happened with bimetallism. The government could control the price of gold and the price of silver for a while, but not permanently. It could control the price of one or the other, but not both. So it dropped silver in 1873. And it could control the price of gold, but not both gold and NGDP. That’s why we had the Great Depression (stable gold and falling NGDP).

“But the Fed realizes that if it did what it took to prevent rates from falling, then this policy would disrupt its long run goals for the economy.”

That’s the way I think of it. It could control 3 month US bonds forever, but then wouldn’t be able to control NGDP permanently. Or, it could just forget about interest rates and control NDGP.

30. March 2018 at 21:04

Scott,

OT, but did you happen to see this one..

http://davidsplinter.com/AutenSplinter-Tax_Data_and_Inequality.pdf

31. March 2018 at 00:34

dtoh, Yes, I find that sort of critique of Piketty to be plausible. I haven’t read the paper, but I certainly agree that there are lots of problems with the way Piketty interprets the income distribution data.

This year my reported income was very high, putting me in the top 1%. But my actual income was barely 1/3 of my reported income. I am even more convinced than before that the income distribution data is meaningless.

31. March 2018 at 13:09

I also thought their conclusions on effective tax rates were interesting. For the top 1%, effective federal tax rates were

1960 – 16%

2004 – 23%

1. April 2018 at 18:24

Yes, Federal taxes are quite progressive.

2. May 2018 at 07:59

“I believe the language we use matters. In this case, the dominant Fed-sets-rate language makes it easy to assume that the federal funds rate is low because the Fed’s target is low. It makes it difficult to even consider the possibility that the Fed’s target is low because the market-clearing federal funds rate is low.”

Great point Will.