The Keynesian blind spot

I’ve seen recent signs that the gap between Keynesians and market monetarists is narrowing. David Beckworth reached out to fiscal advocates in a recent post, and Ryan Avent also tried to bridge the gap. As you’d expect, Martin Wolf’s new piece in the NYR of Books ends up in a suitably ecumenical fashion:

The right approach to a crisis of this kind is to use everything: policies that strengthen the banking system; policies that increase private sector incentives to invest; expansionary monetary policies; and, last but not least, the government’s capacity to borrow and spend.

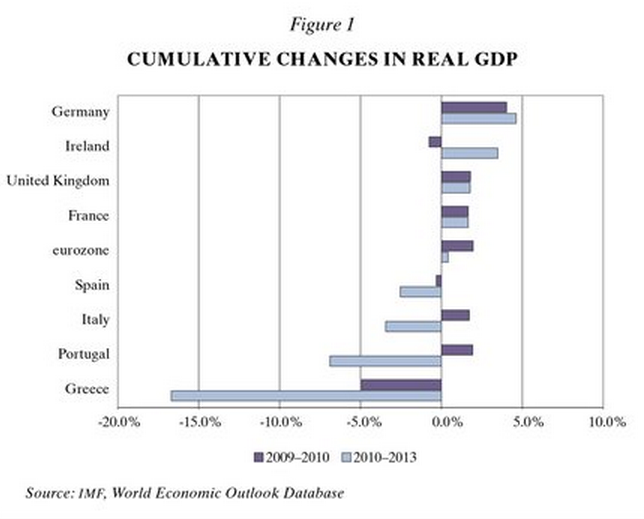

But I also see a huge blind spot in Wolf’s piece, which slants the results in a very revealing way. Wolf provides a blow-by-blow account of how fiscal austerity slowed the recovery after 2010, and provides this graph to illustrate his points:

A few comments. Wolf uses RGDP, which combines the effects of supply and demand shocks. He should use NGDP, since his argument relates to austerity. If he had, the British performance would look far better than the eurozone performance. Britain has bigger supply-side problems that many Keynesians acknowledge. Also note that the second bar shows total growth over three years, thus even Germany has done poorly since 2010, worse than the US.

But here’s the big problem. Wolf’s careful account of how austerity pushed the eurozone back into recession completely ignores the elephant in the room—the ECB’s sudden move toward tight money in 2011. Indeed Wolf cites interest rate data that gives the casual reader a very misleading impression:

Why is strong fiscal support needed after a financial crisis? The answer for the crisis of recent years is that, with the credit system damaged and asset prices falling, short-term interest rates quickly fell to the lower boundary””that is, they were cut to nearly zero. Today, the highest interest rate offered by any of the four most important central banks is half a percent.

It’s really hard to imagine a more misleading description of ECB monetary policy over the past 5 years. Yes, current ECB target rates are 1/2%, and they’ve been there for one month, i.e. for 2% of the past 5 years. In 2011 the ECB was raising rates from 0.75% to 1.25% to slow the recovery, out of fear of inflation. Had fiscal policy been more expansionary, monetary policy would have been even more contractionary. Even Paul Krugman admits that fiscal stimulus is only effective when at the zero bound. And the eurozone crisis occurred when the eurozone was not at the zero bound, indeed policy was being tightened in the most “conventional” fashion imaginable—higher short term interest rates.

Update: Mark Sadowski corrected me–the ECB actually raised rates from 1.0% to 1.5% in 2011.

So fiscal austerity did not create the eurozone double dip recession; tight money did. Still, I don’t want to be too hard on Mr. Wolf—he’s a great journalist and in a sense we are on the same side. We both believe that weak AD (which I define as NGDP) is the core eurozone problem. But the problem is not fiscal austerity, it’s austerity more broadly defined, an irrational fear of rising nominal spending.

Yichuan Wang has a nice post showing that many economists have misremembered (is that a word?) the events of late 2008. At no time during the great NGDP crash of June to December 2008 was the Fed at the zero bound. Money was too tight, but for eminently conventional reasons:

The zero lower bound didn’t always bind. For three months after Lehman’s collapse on September 15, 2008, the federal funds rate stayed above zero. In this period of time, the Fed managed to provide extensive dollar swaps for foreign central banks, institute a policy of interest on excess reserves, and kick off the first round of Quantitative Easing with $700 billion dollars of agency mortgage backed securities. Finally, on December 15, 2008, the Fed decided to lower the target federal funds rate to zero.

It is important to remember the sequence of these events. It is easy to think that the downward pressure on interest rates was the inevitable consequence of financial troubles. Yet the top graphic clearly contradicts this. Each of the dotted lines represents a FOMC meeting, and each of these meetings was an opportunity for monetary policy to fight back against the collapsing economy. The Fed’s sluggishness to act is even more peculiar given that there were already serious concerns about economic distress in late 2007. As, the decision to wait three months to lower interest rates to zero was a conscious one, and one that helped to precipitate the single largest quarterly drop in nominal GDP in postwar history. The chaos in the markets did not cause monetary policy to lose control. Rather, the Fed’s own monetary policy errors forced it up against the zero lower bound.

This is not to say those mistakes were purposeful. But in the high stakes game of central banking, even benign neglect can be dangerous. These failures in the last three months of 2008 can teach us many lessons about what should be done for future monetary policy. Only this way can we be more sure that careless mistakes won’t jeopardize the future path of monetary policy.

One of the first steps would be to switch to a nominal GDP target.

Yichuan then explains how NGDP targeting would improve Fed performance. I also recommend this interesting Wang post, one of many I don’t have time to adequately discuss. It tries to combine NGDP targeting with the Taylor Rule approach.

PS. This post over at Free Exchange discusses a BIS report making an even worse mistake than Wolf:

CENTRAL banks are unable to repair banks’ broken balance sheets, to put public finances back on a sustainable footing, to raise potential output through structural reform. What they can do is to buy time for those painful actions to be taken. But that time, provided through unprecedented programmes of monetary stimulus since the financial crisis of 2008, has been misspent. Neither the public nor the private sector has done enough to reduce debt and to press ahead with urgent reforms. Yet only a forceful programme of repair and reform will allow economies to return to strong and sustainable growth.

That is the message from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the closest that central bankers have to a clearing-house for their views.

Nope, ECB policy was ultra-tight, especially in 2011. That caused a eurozone NGDP growth collapse, and explains why so little progress has occurred on the debt front.

PPS. Maybe this post was poorly named. If there is a Keynesian blind spot, what do you call the BIS view?

Tags:

23. June 2013 at 14:05

“If there is a Keynesian blind spot, what do you call the BIS view?”

It’s the view of severely addled central bankers who are deeply committed to remaining completely oblivious to reality no matter what.

And the BIS has been this way since the very beginning:

“In view of all the events which have occurred, the Bank’s Board of Directors determined to define the position of the Bank on the fundamental currency problems facing the world and it unanimously expressed the opinion, after due deliberation, that in the last analysis “the gold standard remains the best available monetary mechanism” and that it is consequently desirable to prepare all the necessary measures for its international reestablishment.”

BIS Third Annual Report, May 1933

http://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/archive/ar1933_en.pdf

Depression? What Depression?

23. June 2013 at 14:27

“In 2011 the ECB was raising rates from 0.75% to 1.25% to slow the recovery, out of fear of inflation.”

Actually that’s incorrect Scott. The ECB’s policy rate is the Main Refinancing Operations (MRO) rate which was 1.0% from May 13 2009 through April 12, 2011. It was raised to 1.25% on April 13, 2011 and to 1.50% on July 13, 2011. The first time it was lowered to 0.75% was on July 11, 2012, which was less than a year ago.

http://www.ecb.int/stats/monetary/rates/html/index.en.html

23. June 2013 at 14:31

The BIS report demonstrates a complete lack of understanding of monetary policy and AD. If central banks are making it too easy for governments, then should central banks tighten every time there is a supply-side recession? At the slightest hint of necessary reform, central banks should kill AD to make the recession into a depression and force governments to enact reform!!!

23. June 2013 at 14:38

Mark Sadowski,

“A great war has a double aspect: on the one hand, severance of relations with enemies and, on the other, a closer association among countries on the same side of the barrier. Thus, contrasting with the element of isolation, an active element of collaboration is present.”

BIS Twelfth Annual Report, June 1942

http://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/archive/ar1942_en.pdf

23. June 2013 at 14:40

Monetary Silo Effect – defining “monetary policy” as managing I, or MB, in isolation.

23. June 2013 at 15:00

“Blindspots” everywhere. Israel just chose as CB chief to replace Fischer the wrong Frenkel:

http://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2013/06/23/israel-makes-a-politically-correct-choice/

23. June 2013 at 17:29

“The right approach to a crisis of this kind is to use everything: policies that strengthen the banking system; policies that increase private sector incentives to invest; expansionary monetary policies; and, last but not least, the government’s capacity to borrow and spend.”

Wolf clearly doesn’t understand the nature, causes, or cures of the crisis.

——————

Dr. Sumner:

“Wolf’s careful account of how austerity pushed the eurozone back into recession completely ignores the elephant in the room””the ECB’s sudden move toward tight money in 2011.”

Sumner’s careful account of how monetary tightening (measured by NGDP) pushed the eurozone back into recession completely ignores the elephant in the room “” the ECB’s previously loose money prior to 2011 (which may be associated with stable, falling, or rising NGDP over time).

23. June 2013 at 17:56

The market monetarist blindspot:

Distortions to intertemporal economic calculation brought about by non-market money monopolies.

23. June 2013 at 18:08

Thanks Mark, I corrected it.

Marcus, He was my professor at Chicago.

23. June 2013 at 19:03

Scott

Maybe you should give him a call!

23. June 2013 at 19:17

Repeat after me, all central bankers: Print more money, and keep printing money, until the major economies of the world are running red hot—and then, and only then, think about inflation.

Next problem.

23. June 2013 at 19:24

Benjamin Cole:

I can’t help but picture you and as this:

http://i.imgur.com/fnrBdsP.jpg

23. June 2013 at 19:26

Benjamin Cole:

I can’t help but picture you as this:

http://i.imgur.com/fnrBdsP.jpg

23. June 2013 at 21:43

Mr. Sumner, what do you think – how (a)symetrical are the effects of ECBs rate movements? Is AD more “sensitive” to negative shocks (ECB raising minimum bid rate) than to ECB lowering rates. Do models usually show symmetrical or do they take in account a possibility of an asymmetrical response of NGDP (and other variables)?

Greets

24. June 2013 at 00:57

To get it totally wrong in one decade may be regarded as justifiable ignorance; to get it wrong in another decade in EXACTLY THE SAME WAY looks like a fundamental problem with the profession.

The Martin Wolf piece epitomizes how Keynesians have distorted even the basic interpretation of the crisis, let alone the facts. The BIS piece is just a sliver of how austerianism has extended beyond online comments sections and the Rothbard fanclub over at Mises.org (who’d condemn Mises as a socialist if it wouldn’t make them look so silly) and into the corridors of power.

And somehow, someway, Richard Koo has managed to combine the worst of both these elements.

24. June 2013 at 03:19

[…] See full story on themoneyillusion.com […]

24. June 2013 at 05:45

Scott writes: “Maybe this post was poorly named. If there is a Keynesian blind spot, what do you call the BIS view?”

Your Blind Spot is ignoring/downplaying conservatives pushing tight money. As Krugman pointed out a week or so ago, Keynesians are not opposed to expansionary monetary policy and most are willing to give it a try, but it is the conservatives that are loudly opposed to any monetary easing.

Here is John Boehner, for example, “But this quantitative easing, I’ve been concerned about. I think it’s over the top and puts us in very dangerous territory. And I understand his concern’s more about deflation than it is inflation but you can’t continue to debase the currency long term, it’s just not a healthy thing. […] Well,I– again I’ve been concerned about this quantitative easing. You can’t continue with virtually zero interest rates for a long time. It’s–you’re telling investors you only have one place to go, and that’s to the equity market. It’s– we all knew this day was going to come when he was going to start to back up a little bit — better now than later.” http://www.cnbc.com/id/100832114?__source=yahoo|finance|headline|headline|story&par=yahoo&doc=100832114|CNBC%20Exclusive:%20CNBC%20Tran

Boehner isn’t an economists, but John Taylor is. “The planned asset purchases risk currency debasement and inflation, and we do not think they will achieve the Fed’s objective of promoting employment.” http://economics21.org/commentary/e21s-open-letter-ben-bernanke

And there’s John Cochrane, “Applying both theory and data summarizing historical experience, Cochrane concluded that recent monetary policy is remarkably ineffective.” http://bfi.uchicago.edu/events/20130530_cochranetalk.shtml Note that talk was at the Becker Friedman Institute.

The BIS report is simply what “everyone knows” in conservative circles. You can go on acting like Keynesians are the problem, but that would be ignoring the elephant in the room (pun intended).

24. June 2013 at 06:39

Marcus, He wouldn’t remember me.

Petar, It’s not a question of symmetry, the problem is that the effects are time-varying. The same interest rate move can have dramatically different effects at different points in time, for all sorts of reasons.

W. Peden, Yes, they never learn.

Russ, You said;

“Your Blind Spot is ignoring/downplaying conservatives pushing tight money.”

Obviously you haven’t read my most recent post. And I’ve done many posts criticizing conservatives on tight money, including the names you mention. If I don’t do more then perhaps because I feel that it’s like shooting ducks in a barrel. Not very sporting. There are simply no good arguments for tighter money under the Fed’s current policy regime. Not one. Liberals should be honored than I focus on them.

BTW, It is Obama appointees at the Fed who are enacting these insane polices, so I hardly think liberals are blameless. The only dissenter toward easier money was a conservative at the St. Louis Fed–a bastion of monetarist thought (or at least it used to be.)

24. June 2013 at 06:51

[…] as Geoff, back at Scott´s blog, in a rare moment of good humor indicates, Benjamin Cole reminds him of this […]

24. June 2013 at 10:14

It’s good he’s coming around on monetary policy, but Wolf is one of those more-Keynesian-than-Keynes types who believe the fiscal stimulus of WW II is what ended TGD because GDP rose and unemployment fell, never mind that living standards declined dramatically because millions of men were conscripted and consumer goods were tightly rationed while we produced lots of GDP-boosting goods useful primarily for killing people and breaking things across Europe, Asia, and the Pacific Rim.

So, let’s agree that the “austerian” tax hikes were a bad idea — no one on the small-gov’t right ever favors tax hikes anyway. Well then, what happened to spending? Well, despite furious efforts to <a href="http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/06/05/heritage-shock/?_r=0"obscure the facts by the anti-austerians, spending hasn’t fallen.

So the anti-austerians are left essentially arguing the government should be spending even more borrowed money than the levels that propelled them into insolvency. This is not a solution, this is ideology run amok, and no one should take these arguments seriously.

24. June 2013 at 10:16

Sorry, bad tag! My kingdom for a preview/edit option.

It’s good he’s coming around on monetary policy, but Wolf is one of those more-Keynesian-than-Keynes types who believe the fiscal stimulus of WW II is what ended TGD because GDP rose and unemployment fell, never mind that living standards declined dramatically because millions of men were conscripted and consumer goods were tightly rationed while we produced lots of GDP-boosting goods useful primarily for killing people and breaking things across Europe, Asia, and the Pacific Rim.

So, let’s agree that the “austerian” tax hikes were a bad idea — no one on the small-gov’t right ever favors tax hikes anyway. Well then, what happened to spending? Well, despite furious efforts to obscure the facts by the anti-austerians, spending hasn’t fallen.

So the anti-austerians are left essentially arguing the government should be spending even more borrowed money than the levels that propelled them into insolvency. This is not a solution, this is ideology run amok, and no one should take these arguments seriously.

24. June 2013 at 20:47

Scott wrote “Obviously you haven’t read my most recent post. And I’ve done many posts criticizing conservatives on tight money, including the names you mention.”

I’ve read enough to notice the trend and the few exceptions.

“If I don’t do more then perhaps because I feel that it’s like shooting ducks in a barrel. Not very sporting.”

Ah, sporting. Never would have guessed that reason.

“There are simply no good arguments for tighter money under the Fed’s current policy regime. Not one. Liberals should be honored than I focus on them.”

Honored that you complain more about the people that do not object to more easing, while not focusing on those opposed to easing, because it wouldn’t be sporting? I don’t get that.

25. June 2013 at 05:51

Russ, This is a blog, and I’m an academic, not a politician. I like to discuss interesting ideas. If I don’t find an idea interesting I generally don’t discuss it. I find Krugman’s ideas interesting, and influential. I rarely criticize most of the other liberal bloggers.

One can only do so many pieces mocking Richard Fisher before one gets tired of it. (I’ve done plenty) I’d add that I only have so much time, and hence read relatively few conservative blogs that oppose monetary stimulus. Most of the blogs I read (liberal and conservative) favor monetary stimulus.

25. June 2013 at 06:55

Russ makes a fair point — as much as I disagree with Krugman/BDL, I sometimes feel like every criticism should include a disclaimer “not nearly as wrong as most people on the right, at least on monetary policy.” 🙂

Clearly everyone from Paul Ryan to Mitt Romney to Sarah Palin to John Boehner to Mitch McConnell to Rick Perry is on the wrong side of monetary stimulus.

I think Scott does a reasonable job though.

25. June 2013 at 19:01

Obviously fiscal austerity would have an impact on NGDP and RGDP in countries which don’t have their own currency. That is 100% consistent with market monetarism.