That “ungainly” NGDP

Mishkin’s Monetary Economics textbook defines AD in two different ways; once as a rectangular hyperbola, i.e. a given level of NGDP, and then again using the approach preferred by Keynesians, which I have always found to be so confusing and illogical that I have never bothered to try to figure it out. (Of course this creates problems when students ask me to explain the “three reasons the AD curve slopes downward.” I usually tell them to ignore that section of the principles text, and assume AD is a given level of nominal aggregate expenditure.) Cowen and Tabarrok’s text also uses the AD=NGDP approach that I prefer, and even better, uses rates of change. (BTW, don’t miss my update below.)

I was reminded of this distinction when reading this passage from a recent FT column by Samuel Brittan:

It is vital that any new regime incorporates the low inflation philosophy and does not throw out the baby with the bath water. The proposal of Olivier Blanchard, the International Monetary Fund‘s chief economist, to raise inflation targets to 4 per cent is the perfect example of how not to proceed. If we can go from 2 to 4 per cent, why not from 4 to 6 per cent or from 6 to 8 per cent and so on?

The alternative to inflation targets has long been known. It goes by the ungainly name of nominal gross domestic product. This is just the familiar GDP, but before adjusting for inflation. A nominal GDP objective was for long championed by the British economist James Meade, although it was implicit in many other proposals. I have often thought that its name is the main obstacle to its acceptance and have suggested paraphrasing it as a national cash objective.

The basic idea is that monetary and fiscal policy cannot “manage” demand and output in real terms, as so many postwar experiences demonstrated. What it can endeavour to do is to maintain the growth of cash spending by an amount sufficient to sustain normal growth if costs and prices remain stable. It is a fairly subtle compromise between an output and an inflation target. If the nominal GDP target is, as is likely, just over 5 per cent per annum, then if there is no inflation it is equivalent to an output target of that amount. But if inflation rises to 5 per cent the emphasis shifts to bringing it down, even at the cost of temporary stagnation of real output.

A huge advantage of this is that it lessens dependence on forecasts. If politicians overestimate the trend of output growth then inflation will rise and policy will automatically become more restrictive. If they underestimate it, policy becomes more expansionary.

. . .

I had originally thought that there should be a period of reflection on such questions before installing a new regime to replace or supplement inflation targets. But I have been impelled to a sense of urgency by Giles Wilkes’s Centre Forum paper on the Bank of England’s policy of quantitative easing, “Credit where it’s due”. He has a number of sensible proposals for making this easing “a more effective stimulant and not just a tonic for the City”. But at the top of his list is an explicit target for “nominal growth”. This might counteract fears that the easing will be withdrawn before it has become effective – and I would add depressing talk of higher bank capital ratios and national fiscal tightening. Something needs to be done to create headroom for economic recovery.

UK nominal GDP at the end of last year was perhaps 15 per cent below its earlier trend line. This was not a cause of the recession, but a reflection of it. It did however indicate that there was a lot of room for continued stimulus before hitting the inflation buffers.

Of course it was the cause of the recession. The recession was caused by a severe AD shock, i.e. falling NGDP. If it had been caused by an AS shock then the recession would have been accompanied by higher inflation. It would really help if people started to think more in terms of NGDP.

And how about this quotation?

It goes by the ungainly name of nominal gross domestic product. This is just the familiar GDP, but before adjusting for inflation.

Imagine a journalist describing interest rates as follows: “It goes by the ungainly name of nominal interest rates. This is just the familiar interest rate, but before adjusting for inflation.” Or do the same thought experiment for nominal wages, or any other nominal variable. How sad that we need to explain the concept of NGDP, i.e. aggregate demand, to the readers of the FT. Confusion in language often suggests confusion in thinking. But it’s nice to see the 5% NGDP target mentioned by a prominent journalist.

HT: Marcus

Update: One hour after writing this section, Mishkin’s new (9th) edition arrived in my office mail. I will teach out of it this fall. In a bizarre coincidence, the 9th edition completely eliminated my favorite part of the book, the presentation of AD as a rectangular hyperbola. Instead he only uses the convoluted Keynesian approach to the derivation of AD. I am beyond angry, and will retaliate by exposing some very embarrassing flaws in Mishkin’s book:

Because the classical economist (including Fisher) thought that wages and prices were completely flexible, they believed that the level of aggregate output Y produced in the economy during normal times would remain at the full employment level, so Y in the equation of exchange could also be treated as reasonably constant in the short run. (p. 501)

None of the classical economists believed this. Most believed the same thing that modern new Keynesians believe—that wages and prices were sticky, and that this is why nominal shocks caused business cycles. If there is an odd man out, it is the Keynes of the General Theory–who insisted that nominal shocks would have real effects even if wages and prices were completely flexible. Why do textbook writers keep writing this nonsense? Here’s another:

Until the Great Depression, economists did not recognize that velocity declines sharply during severe economic contractions. Why did the classical economists not recognize this fact when it is easy to see in the pre-Depression period in Figure 1? Unfortunately, accurate data on GDP and the money supply did not exist before World War II. (p. 503)

We still don’t have accurate data on GDP, but there were certainly many estimates of national income during the interwar years, and they were reasonable accurate. And they knew the money supply, at least as they defined money at that time. So the interwar economists knew that velocity often fell during recessions. Indeed Fisher spent a lot of effort trying to explain why velocity changed. If they really believed velocity was constant, then they would have been monetarists—advocating steady growth in the money supply. Again, this is a statement made in many textbooks, which is completely erroneous.

All of these misconceptions tend make modern macroeconomists smug. We think we have advanced far beyond the pre-Keynesian macroeconomists, whereas we are in many respects still far behind them. They knew how to boost the price level when nominal rates hit zero, something many modern macroeconomists have forgotten.

Long time readers of this blog know how frequently I refer to Mishkin’s 4 basic principles of monetary economics. These 4 principles are totally at odds with the standard view of what went wrong in 2008. Thus I have been wondering how Mishkin would address this issue in his new edition. After all, he also held the conventional view in 2008. Would the 4 principles mysteriously disappear, like the missing faces of purged officials in old photos of Stalin? No they are still there, but Mishkin adds an explanation of the 2008 crisis that is completely at odds with those principles:

With the advent of the subprime financial crisis in the summer of 2007, the Fed began a very aggressive easing of monetary policy. The Fed dropped the target federal funds rate from 5 1/4% to 0% over a fifteen-month period from September 2007 to December 2008. (p. 609)

Actually, the rate was cut to 0.25%, but that inconvenient fact gets in the way of the preferred narrative that they did all they could. Then just one page later, Mishkin begins summarizing his 4 basic principles—seemingly oblivious to the fact that they conflict with his account of the recent crisis:

1. It is dangerous always to associate the easing or tightening of monetary policy with a fall or a rise in short-term nominal interest rates.

Except, apparently, during 2008.

2. Other asset prices besides those on short-term debt instruments contain important information about the stance of monetary policy because they are important elements in various monetary policy transmission mechanisms.

Yet just a few paragraphs earlier, when discussing the recent crisis, Mankiw Mishkin had said this:

The decline in the stock market and housing prices also weakened the economy, because it lowered household wealth. The decrease in household wealth led to restrained consumer spending and weaker investment, because of the resulting drop in Tobin’s q.

With all of these channels operating, it is no surprise that despite the Fed’s aggressive lowering of the federal funds rate, the economy still took a bit hit. (p. 610, I think he meant “took a big hit.”)

Just one day after criticizing Krugman’s rude tone, I shouldn’t be so sarcastic about Mishkin. Especially because I like Mishkin a lot, and he’s a much better monetary economist than I am. But I can’t hold back. Here’s what Mishkin is doing: In his grand summary he argues that short term rates aren’t a good indicator of the stance of monetary policy. Then he argues that we need to look at asset prices to see what was really going on. If asset prices are plunging, monetary policy may be too tight, even if rates are near zero. But when it comes to the sub-prime crisis, all this goes out the window. Now he views falling asset prices as something unrelated to monetary policy, an exogenous shock that depressed output despite the Fed’s best efforts. But did the Fed really give it’s best effort?

3. Monetary policy can be highly effective in reviving a weak economy even if short-term interest rates are already near zero.

But if this is the case, then why weren’t those plunging asset prices an indicator that money was way too tight, relative to the needs of the economy, despite the low nominal rates?

It gets even worse when you read the paragraphs under each key principle. Under the first point Mishkin adds:

As Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz have emphasized, the period of near-zero short-term interest rates during the contraction phase of the Great Depression was one of highly contractionary monetary policy, rather than the reverse.

Of course Mishkin could point to the monetary aggregates, which did behave differently during the recent crisis than the Depression. But is that really where moderate new Keynesians like Mishkin want to take their stand? Remember that new Keynesians criticized money supply indicators, and point to Japan as an example of where an increasing money supply did necessarily indicate easy money.

And under the third key principle Mishkin emphasizes the need to raise inflationary expectations once nominal rates hit zero—something Bernanke has explicitly refused to do (when asked by DeLong.) But Mishkin argues elsewhere that Bernanke has done a good job. I really can’t image any plausible defense for the inconsistency in Mishkin’s new addition. And even if there is one, what are the odds that if I can’t figure it out, our undergraduate students (presumably with much more subtle minds than I have) will decipher the underlying explanation for the seeming inconsistency between Mishkin’s account of the 2008 crisis, and his grand summary of the basic principles of monetary economics? Yes, I’m being sarcastic. But this section of the book seems like a major train wreck—and in the worst possible place. This is precisely the topic that you’d expect a monetary economics textbook to say something useful about; the crisis of 2008.

Part 2. FDRs’ first year in office.

A September 2008 AER paper by Gauti Eggertsson argued that FDR brought in a regime change, a much more expansionary fiscal and monetary policy. Eggertsson was a student of Woodford’s and all three of us think current AD is strongly impacted by expected future AD. So this policy change should have had an immediate impact on current levels of AD (and by implication, commodity prices.) Krugman is supposed to think this as well, but sometimes he forgets this point, as when in his NYT columns he criticizes Republicans for arguing as early as 2009 that fiscal stimulus had failed, before much of the projected spending had even occurred. If fiscal stimulus is expected to work at all, it will mostly affect AD when it is announced, not when the money is spent. It should have started working the day Obama was elected, if not sooner, according to the new Keynesian model. The markets didn’t expect it to work, because $800 billion in stimulus doesn’t do much good.

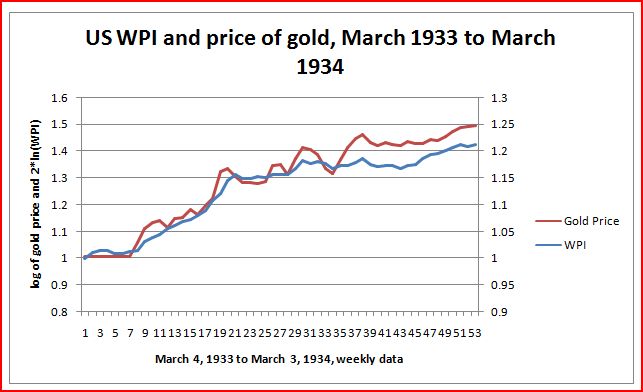

As you know, the economy took off like a rocket soon after FDR took office, but if you look closely at the weekly data for the WPI, his policy of “reflation” didn’t start bearing fruit until FDR began raising the price of gold in the later part of April, 1933. Take a look at this graph, which shows the relationship between the weekly WPI, and the dollar price of gold:

So there isn’t really any evidence that FDR’s other measures, such as fiscal stimulus, had much effect. Instead, prices rose sharply when the dollar was devalued, and stopped rising when the value of the dollar leveled off. (BTW, I’m still working on better labelling for the graph. The right scale is the WPI, which rose less sharply than the price of gold (left scale.)

This graph shows why I think price level or NGDP targeting are far more powerful than traditional monetary policy tools. Interest rate targeting obviously became ineffective once nominal rates fell close to zero in 1932. And even the open market purchases of bonds during the spring of 1932 weren’t very stimulative. But if you set a higher price level target, and/or directly change the price of money, then the effect will be much more expansionary. Dollar devaluation raised current prices, and raised future expected prices even more.

This graph is the first of many graphs that I am adding to my manuscript at the suggestion of others. The material for chapters 4-6 that I have posted on this blog will eventually be augmented by similar graphs. I will post some of the graphs here to see if you have any comments.

Tags:

28. March 2010 at 11:02

“Of course it was the cause of the recession. The recession was caused by a severe AD shock, i.e. falling NGDP. If it had been caused by an AS shock then the recession would have been accompanied by higher inflation. It would really help if people started to think more in terms of NGDP. ”

Hrm, I can’t agree with this as the recession was preceded (if you think it started when you do, Scott.) or started with (if you agree with the BLS on when it started) by a large supply shock. Food, energy, and some raw materials were in a severe adverse AS shock. Then very shortly after the AS shock, we had an AD shock, because NGDP was allowed to fall.

The AD shock wasn’t by itself, nor do I think it was big enough to be enough by itself.

28. March 2010 at 12:02

Scott:

I was please too to Samuel Brittan’s piece and did a quick write up on it. He is on to something here. Selling anything is often how you market it and using the terms NGDP targeting, stabilizing AD, or stabilizing nominal expenditures is not going to get this idea a wide hearing. His suggestion of framing it along the lines of “stabilizing cash spending” makes it accessible to many and is brilliant in my view.

28. March 2010 at 12:18

Scott,

I learned money banking and finance from Mishkin’s 7th edition and love the book. The changes you describe are distressing. I’m tutoring a group in the subject right now. Even my students prefer my textbook to their own.

On a somewhat different note I’ve been playing with Tabarrok and Cowen’s AS/AD diagram (I’m like a four year old with a new toy). If you place the LRAS curve at 2.7% real growth and move the SRAS and AD curves so that they all intersect at an inflation rate of 3.3% (deflator) you will get the situation that existed in 2006. To get to 2007 (2.1% real growth and 2.9% inflation) the only way possible is by moving the AD curve. Ditto for 2008 (0.4% growth and 2.1% inflation). 2009 (-2.4% real growth and 0.8% inflation) is more complicated as the Tabarrok/Cowen diagram implies that there is combination of a negative AD shock and a positive SRAS shock.

In short using their diagram and annual data I find absolutely no evidence of a negative supply side shock. Rather, there appears to be a positive supply side shock in 2009. Interestingly labor productivity also soared (and unit labor costs plummeted) in 2009.

28. March 2010 at 12:53

[…] moment has finally come. Scott Sumner’s blog has mentioned the piece in passing, as part of Sir Samuel Brittan’s column of a week or two […]

28. March 2010 at 14:20

A few years ago, a friend was doing a Health Policy M.A. and was confronted with the choice of doing microeconomics or macro. I strongly recommended micro since I had been deeply sceptical about macroeconomics ever since I did first year economics. Post like these just remind me of why I am very glad to have given that advice.

28. March 2010 at 14:42

What is the rationale for Mishkin’s approach?

The Fed is always right.

28. March 2010 at 16:00

Scott:

The slope of the AD curve (like any demand curve) depends on what you hold constant when you draw it. And if you hold “monetary policy” constant, that depends on what the monetary policy is.

Yes, if the Fed (successfully) targets NGDP, then the AD curve is a rectangular hyperbola.

If the Fed (successfully) targets inflation, the AD curve is horizontal.

If the Fed (successfully) targets M, the AD curve is steeper than a rectangular hyperbola. (That’s the standard ISLM case)

If the Fed (successfully) targets a nominal interest rate, the AD curve is vertical (and the economy either explodes or implodes).

If the Fed (or the central bank of a small open economy) (successfully) targets the nominal exchange rate, the slope of the AD curve depends on the elasticity of demand for net exports wrt the real exchange rate.

And, in each case, you get a very different theory of why the AD curve slopes down (if it does).

If you want the Fed to target NGDP, then you *want* the AD curve to be a rectangular hyperbola. But actual curves don’t always have the shape we *want* them to have.

Plus, a picky point: there’s NGDP, NGDP demanded, and NGDP supplied. Three different things. In the US, NGDP usually equals NGDP demanded. In Cuba, NGDP is usually much less than NGDP demanded (P is fixed, and there are queues for most things).

28. March 2010 at 16:06

That graph of WPI against gold price is very impressive. Does it look equally good over longer periods?

28. March 2010 at 17:21

You don’t mean Mankiw here, right? Easy to confuse one textbook author with another, of course…

28. March 2010 at 17:38

Doc Merlin, You are right. I meant the severe phase of the recession that began in August 2008–that part that was caused by a fall in AD.

David, That’s a good point. But does it help to sell it to macroeconomists? The public doesn’t pay much attention to alternative policy rules (unless they sound evil, like wage targeting.) You need to sell it to people like Bernanke

Mark, I don’t have time to do as much analysis as you did, but I always saw it as being mostly demand shock driven, as you indicated. But I did think AS declined a bit in the first half of 2008. Maybe annual data doesn’t show that, or maybe I’m wrong.

Lorenzo, Yes, but if macro’s flawed then all the more reason to study it and reform it.

Bill, Good question.

Nick, I guess you and I look at AD differently, as I consider it NGDP regardless of the Fed’s target. If they aren’t targeting NGDP, and NGDP changes, then I consider that a shift in AD. The Fed may not consider falling NGDP to be tight money, but I do. Obviously the Fed is not currently targeting NGDP, it has fallen well below trend. I consider that a decline in AD, the hyperbola has shifted to the left.

I suppose the one weakness of my defintion (and it is a definition, not a theory), is that things that the Keynesian model considers to be pure AS shocks would get entangled with AD, and cause NGDP and thus AD to shift if the money supply or interest rates were held constant. I think your point is related to that issue. To prevent a supply shock from shifting AD, monetary policy would have to target NGDP. But I don’t mind AS and AD being a bit entangled. I don’t consider AD to be a demand curve, indeed I don’t even like the term AD, as it suggests a relationship to microeconomic demand that I don’t think is there. To me, macro is all about:

1. Nominal expenditure determination.

2. How changes in nominal income get partitioned between prices and output.

So let’s make that explicit, instead of beating around the bush.

Nick#2, No, massively unimpressive. The price of gold (in the US) was a horizontal line for 54 years before 1933, and 35 years after. And the correlation between a changing variable and a constant is . . . zero I think (my stat is rusty.) What is impressive is that the timing of various recoveries is correlated with when they left gold and devalued. That’s a nice natural experiment that others have commented on. It’s the “gold standard” of identification, pun intended.

28. March 2010 at 17:40

Leigh, Yes, I meant Mishkin. Thanks.

28. March 2010 at 17:47

Scott,

You wrote:

“Mark, I don’t have time to do as much analysis as you did, but I always saw it as being mostly demand shock driven, as you indicated. But I did think AS declined a bit in the first half of 2008. Maybe annual data doesn’t show that, or maybe I’m wrong.”

Evidently I’m on Spring break.

It’s not scientific of course, it’s just noodling. But repeat what I did (I used rice paper) and you’ll see. You’re more right than you know. If I were you I’d make the argument that there is no evidence of any supply side shock at all and stick to my guns. Check it out.

28. March 2010 at 21:19

@Scott responding to me:

Yah, the fed allowing money to contract during the middle of a supply shock was particularly brutal. Unfortunately our regulators haven’t learned the lesson that supply side caused inflation and deflation must be dealt with on the supply side. And that supply side caused deflation and inflation are valuable signals, trying to fight those signals causes all sort of brokenness in the economy.

On the other hand, I don’t know of a way to separate AD shocks from AS shocks while they are happening. I don’t see how its possible for the fed to do anything like this.

28. March 2010 at 23:15

Oh, also Scott, I forgot to mention. One can only do NGDP targeting in the medium and long term, because of how difficult it is to get NGDP data. What Nick brought up brings up problems with short term interest rate targeting even if we use NGDP targeting in the longer term.

29. March 2010 at 04:37

Mark, Certainly for annual data you are right.

Doc Merlin, I have always favored targeting 12 month forward NGDP. But if 12 month forward expectations are stable, then current NGDP won’t move around too much.

29. March 2010 at 05:59

the stimulus wasn’t $800B. i learned here that you have to remove the parts of the stimulus that the republicrats were going to pass anyway. that at least includes the AMT adjustments. so the stimulus was less, certainly under $700B but perhaps much less. that is, unless you get to include tax cuts due to the effects of reduced AD; then it was far north of a trillion.

30. March 2010 at 05:26

q, That’s a good point. But consider this, in 1981-83, the last severe recession, the deficit rose from 3% to 6% of GDP. In 2007-09 it rose from something like 3% to something like 10% to 12% (I don’t recall exactly.) So anyway you cut it the stimulus was much bigger this time. But the recovery in 1983-84 was probably twice as fast. Why? Because they didn’t have a dysfunctional Fed. The Fed allowed for fast growth in NGDP.

30. March 2010 at 09:27

With regard to the early 80s recession — it was a side effect caused by the Fed’s decision to bring inflation under control. The recession of today serves no such purpose. The Fed simply screwed up.

30. March 2010 at 18:38

I take a slightly different view. I agree with Barro; I think that even with a functional fed, increased fiscal stimulus actually hurts the economy.

30. March 2010 at 18:39

@Richard A.

And that is why we need competition in currencies.

31. March 2010 at 05:33

Richard A, I completely agree.

Doc Merlin, I think that is also my view, unless I misunderstood you.

31. March 2010 at 05:34

Doc, I mean on fiscal policy, I don’t support comp. in currencies.

15. April 2010 at 07:47

Were you aware of this Woodford quote: (JEP 2007)

“The conduct of monetary policy under a forecast-targeting framework would probably not have been greatly different than the policy that the Fed has followed in recent years.

But in the absence of a clearer commitment to a systematic

framework for the conduct of policy, the public has little ground for confidence that the stability achieved over the past decade has not simply been due to luck or

the personalities of particular members of the Federal Open Market Committee, so that the situation could change at any time.”

16. April 2010 at 04:40

Steve, Yes, I did read that. I that suppose that up through 2007 he was correct.