Misleading moralistic macro

Continuing in the theme of cognitive illusions, I’d like to discuss how moralistic reasoning distorts our view of macroeconomics. Consider the following from Salon.com:

During the recent fight over extending unemployment benefits, conservatives trotted out the shibboleth that says the program fosters sloth. Sen. Judd Gregg, for instance, said added unemployment benefits mean people are “encouraged not to go look for work.” Columnist Pat Buchanan said expanding these benefits means “more people will hold off going back looking for a job.” And Fox News’ Charles Payne applauded the effort to deny future unemployment checks because he said it would compel layabouts “to get off the sofa.”

The thesis undergirding all the rhetoric was summed up by conservative commentator Ben Stein, who insisted that “the people who have been laid off and cannot find work are generally people with poor work habits and poor personalities.”

Both liberals and conservatives are engaging in moralistic thinking, and both are wrong. They’re fighting the age-old battle over whether the unemployed are the “deserving poor” vs. the “undeserving layabouts.” To utilitarians like me, there are no “just deserts,” just more or less utility as a result of various public policy options.

I don’t see any evidence that the unemployment problem is caused by laziness. Or perhaps I should say that I doubt the work ethic of the recently unemployed is much different from the employed. There are definitely people who would rather not work if they didn’t have to (like me), especially those with dangerous, dirty, or unpleasant jobs. Or lots of exams to grade. But people also like money, and I’d guess the vast majority of unemployed people would rather be back at work.

But the liberals are also wrong; 99 week unemployment insurance probably does modestly raise the unemployment rate. It’s only natural that a person who loses a fairly good job would like to return to a fairly good job. A laid off accountant would be foolish to accept a job as a maid, janitor or coal miner.

But the main point of my post is that it’s a big mistake to form opinions about the impact of macro policies on the basis of personal observation, or intuition about human nature. And that’s because of the fallacy of composition. If an accountant losses his UI and becomes desperate for work, that doesn’t increase his chances of getting his old accounting job back. But if every unemployed worker loses his or her UI and becomes desperate for work, it does increase the chances of the accountant getting his job back. The reasons are complex.

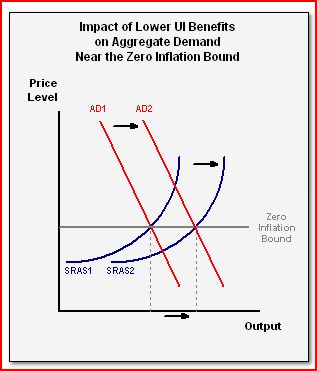

Let’s start by assuming that UI doesn’t affect NGDP, rather the path of NGDP is determined by the Fed. Of course Krugman and Eggertsson would not agree, they’d argue that less UI would reduce NGDP. But recent actions by the Fed indicate that they won’t let inflation fall below about 1%, and that also puts a floor on NGDP. Every time the economy weakens, the Fed does more QE, or at least more talk about future expansionary actions.

If we hold NGDP constant, then how does eliminating UI raise RGDP? It does so by sharply boosting the supply of labor, which depresses the equilibrium nominal (and real) wage rate. Workers who are desperate for work now throw themselves onto the job market. Suppose each worker becomes willing to accept a job paying 40% less than his former job. This lowers wages at all levels, and for any given NGDP that increases employment. It is equivalent to a rise in AD. The accountant who suddenly becomes willing to be a bank teller, paradoxically is more likely to get his old job back, because the general expansion of the economy that results from lower wages leads to a greater need for accountants. Of course this process wouldn’t work perfectly, but there would be some tendency for employment to increase.

So the liberals are right that the unemployed aren’t lazy, but the conservatives are right that less UI would reduce the unemployment rate.

By now you might have assumed that I am advocating cutting UI. If so, you are again engaged in moralistic thinking, assuming that someone making a technical argument is actually making a normative argument. I don’t have strong views on exactly where the UI cut-off should be. In the long run I’d like to see the system reformed to include more self-insurance, but for right now you can make a respectable argument for keeping UI in place, despite the modest increase in unemployment. It does reduce suffering in the short term, suffering caused by needlessly contractionary policies instituted by policymakers who may not even know a single unemployed person. (Oops, now I’m being moralistic.)

One other quick example of the problems with moralistic thinking. Liberals say cutting the estate tax favors people like Paris Hilton. Conservatives counter with stories of family businesses that must be sold off to pay the estate tax. If these were actually the two arguments, I’d go with the liberal view. I’m a utilitarian who thinks a dollar is worth much more to a poor person that a rich person. But I want to abolish the inheritance tax precisely because it’s not a tax on the rich; it’s a tax on capital, whereas we should be taxing consumption. We need a progressive consumption tax.

Part 2: Always avoid annoying alliteration

I just noticed that my last three posts have been entitled Disinflation denial, Avoid asymmetries, and “Misleading moralistic macro. I apologize.