Sahm’s Rule and mini-recessions

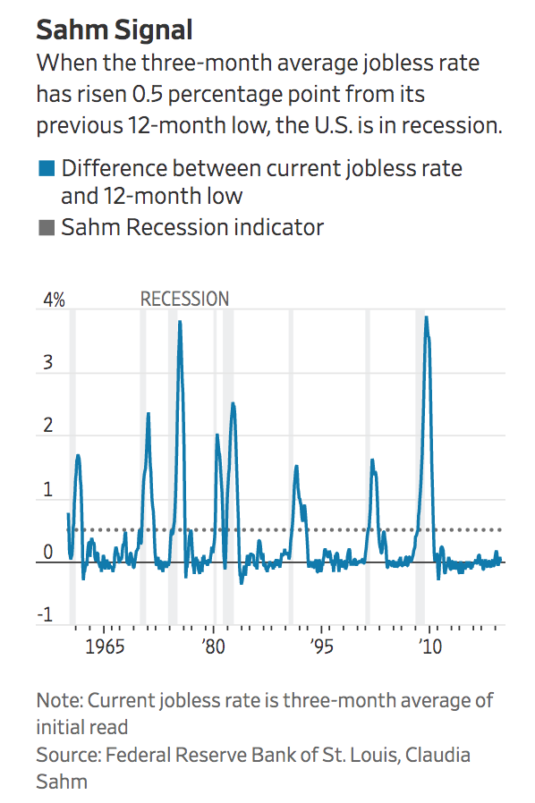

A business cycle forecasting tool developed by Claudia Sahm has recently attracted some media attention. This is from a WSJ article:

Sahm suggested that she got the idea from Jason Furman, who heard about the idea from Doug Elmendorf.

Sahm suggested that she got the idea from Jason Furman, who heard about the idea from Doug Elmendorf.

Back in 2011, I had a similar insight in a blog post on mini-recessions (or more specifically the lack of mini-recessions):

I searched the postwar data, which starts at 1948 and covers 11 recessions. During expansions I found only 12 occasions where the unemployment rate rose by more than 0.6%. In 11 cases the terminal date was during a recession. In other words, if you see the unemployment rate rise by more than 0.6%, you can be pretty sure we are entering an recession. The exception was during 1959, when unemployment rose by 0.8% during the nationwide steel strike, and then fell right back down a few months later. That’s not called a recession (and shouldn’t be in my view.) Oddly, unemployment had risen by exactly 0.6% above the Bush expansion low point by December 2007 (when the current recession began) and by 0.7% by March 2008, and yet many economists didn’t predict a recession until mid-2008, or even later.

What’s my point? That fluctuations in U of up to 0.6% are generally noise, and don’t necessarily indicate any significant movement in the business cycle. But anything more almost certainly represents a recession.

Now here’s one of the most striking facts about US business cycles. When the unemployment rate does rise by more than 0.6%, it keeps going up and up and up. With the exception of the 1959 steel strike, there are no mini-recessions in the US. The smallest recession occurred in 1980, when the unemployment rate rose 2.2% above the Carter expansion lows. That’s a huge gap, almost nothing between 0.6% and 2.2%.

Sahm’s formulation is superior to mine because the month-to-month unemployment rate is noisy. By taking a three-month average in measured unemployment she gets a better view of the underlying trend in actual unemployment. In my 2011 post, I hypothesized that any rise in the actual unemployment rate, no matter how small, was an indicator of recession. Because the data is noisy, I suggested that you’d need more than a 0.6% rise in the measured unemployment rate to be certain that the actual unemployment rate had risen at all:

To understand mini-recessions we first need to understand the monthly unemployment data collected by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. This data is based on large surveys of households. It seems relatively “smooth,” rising and falling with the business cycle. Month to month changes, however, often show movements that seem “too large” by 0.1% to 0.3%, relative to the other underlying macro data available (including the more accurate payroll survey.) So let’s assume that once and a while the reported unemployment rate is about 0.3% below the actual rate. And once in a great while this is followed soon after by an unemployment rate that is about 0.3% above the actual rate. Then if the actual rate didn’t change during that period, the reported rate would rise by about 0.6%.

Sahm says that you need more than a 0.4% rise in the 3-month moving average of measured unemployment.

The FT argued that the Sahm indicator doesn’t really “predict” recessions, as it’s a coincident indicator. But even that is highly useful, as we often don’t know that we are in a recession until 6 to 9 months after it began. The most recent recession began in December 2007, but as late as August 2008 the Fed didn’t even know we were in a recession. By that time, the Sahm rule had been indicating a recession for months.

The Sahm Rule has a deep connection to the mini-recession mystery. The rule works in the US precisely because we never have any mini-recessions (for some unknown and deeply mysterious reason.) It doesn’t always work in foreign countries because they do have mini-recessions.

Tags:

5. November 2019 at 15:42

I can get behind this. At least it is timely.

The rule of a 2 quarter drop in RGDP has the downside that you don’t know if you are in a recession until you have been in one for some time. You might be out of the recession before you even know it happened. And I am not sure how people really “feel” a change in RGDP growth.

I suspect the a flattening in NGDP growth may actually be better than RGDP. It captures the double whammy of falling output and falling inflation / deflation. It is more sensitive to changes in AD.

The NBER is arbitrary. And they have the habit of moving around the endpoints well after the fact.

Regarding the 3 month smoothing, smoothing can be dangerous. Smoothing makes correlations appear that don’t actually exist. And, smoothing delays the timeliness of the indicator.

5. November 2019 at 15:56

Excellent blogging.

This suggests fiscal and monetary policies should be anticipatory and even prophylactic regarding recessions.

Punch early and punch hard at the first whiff of a recession.

The time to suffocate a recession is in its crib.

5. November 2019 at 16:21

Rather than getting too caught up on the exact specification, I would just do a contemporaneous probit model of recession with changes in the unemployment rate (or maybe percent changes in employment) and maybe a number of monthly lags.

5. November 2019 at 17:40

A superior approach is to watch for, say, the 2-year Treasury rate falling below the Fed Funds rate. It is superior, because it should be a good predictor, and given the data available, it seems to be.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=pqyS

And here’s the 10-year:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=pqyV

There was a false alarm in 1998, corresponding to the LTCM crisis.

5. November 2019 at 18:59

ssumner wrote:

Is this really a mystery? Unlike most other nations, the U.S. has a well developed, highly diverse economy spread over a very large geographic area. The U.S. does experience mini (or micro) recessions, where economic distress occurs but doesn’t qualify as a full-fledged national recession (or even as a mini-recession) because when it occurs, it is often too limited in scope, severity, or duration to be identified as such by the NBER’s business cycle analysts.

Instead, we see them occur either regionally or concentrated within particular industries, where their impact in the national level data shows up as slow economic growth. They’re certainly evident within stock market data, where you can even identify the distressed industries and, by extension for where they operate, distressed regions.

I would argue Sahm’s rule makes sense for assessing the relative health of the U.S. economy without too many false positives because the economy benefits from the equivalent of modern portfolio theory, where you have a large number of diverse industries in different portions of their business cycles at any given time. At least, until you have too many industries become synchronized in their down cycles, which is when the U.S. can experience national recessions, and why you wouldn’t otherwise see mini-recessions unless you really get under the hood of the nation’s economy.

There really aren’t many other nations that have that combination of characteristics – in 2019, Japan and China are perhaps the closest to possessing that overall package.

6. November 2019 at 03:53

I think in August 2008, the Fed could see that prices (CPI) had risen more than 2% in the last 3 months alone (not annualized) and oil was over $140 per barrel and they, at least subconsciously, thought that a mild recession was necessary. Biggest forecasting mistake of the last 80 years.

6. November 2019 at 09:29

Apologies for going off topic but if it’s of interest to you I’d love to get your thoughts on the recent Ray Dalio piece. It’s been making the rounds here in Silicon Valley and while it makes overall sense to me I feel that you’d have a much more insightful outlook that I’d love to share with people. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/world-has-gone-mad-system-broken-ray-dalio

6. November 2019 at 09:34

Michael, There were other false alarms, such as 1966.

Ironman, You said:

“The U.S. does experience mini (or micro) recessions,”

Not as I define the term, as periods where unemployment rises by 0.8% to 2.0% and then starts falling.

6. November 2019 at 10:30

Scott,

Yes, and it failed to predict the last two recessions in the 50s. It’s one of those indicators in which seeing it doesn’t mean the Fed doesn’t have time to correct and avoid the recession, but they usually don’t. They did in 1998. It’s a pretty good indicator, but obviously not perfect.

It’s superior to the Sahm approach, obviously because it’s predictive, like the inverted yield curve. But, the Sahm signal is more reliable, and very valuable for the reasons you say.

6. November 2019 at 12:35

Can, I’m not really a fan of that sort of piece. Real interest rates are currently quite low, but I don’t see where that would have the vast implications that he describes.

Wealth inequality is rising, but what matters is consumption inequality, and I don’t see all that much change in that metric.

6. November 2019 at 13:23

ssumner wrote:

Fair enough – that absence is much more difficult to explain. I did see your follow up piece, and I think you’re on the right track with your hunch, but would also include countercyclical fiscal policies in the mix.

7. November 2019 at 15:42

1.) When you look at the unemployment rate or better yet, a prime-age 25-54 employment-to-population ratio, you’ll see that what we’ve had highly auto-correlated outcomes in both directions. Expansion begets expansion, but deterioration also begets deterioration for sustained periods (3-5 years). Labor utilization was falling for an extended period after each of the last three recessions “officially” ended according to NBER.

I’ve written more about this here in case you’re curious: https://medium.com/@skanda_97974/are-recessions-rare-depends-on-the-definition-lessons-from-the-prime-age-employment-rate-447530d17655

2. Other countries have a more mean-reverting business cycle process because the US is the demand generator of last resort, which makes the exchange rate a helpful shock absorber for open economies in search of external demand to sell into when domestic demand is falling short (especially those facing ToT shocks). All hail our persistent current account deficit.

3. The notion of a long-run equilibrium is deceptively tempting. In reality, the US business cycle is very path-dependent. Expansion begets expansion, contraction begets contraction. And yet if you believe in supply-side long-run equilibrium conditions kicking in (naturally moving output back to potential and U to U*), it actually perpetuates insufficient policy response of the type you have correctly criticized