Nothing like the 1960s?

Commenter Michael Sandifer left this comment:

One key difference between the current period and ’66 is that inflation is tame.

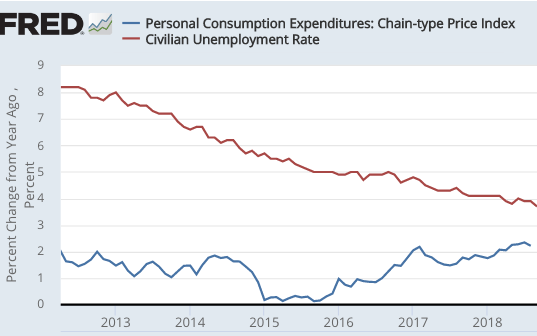

He’s referring to our relatively low inflation:

Over the previous 6 years, unemployment has fallen from 8% to 3.7%. Inflation has mostly stayed in the 1% to 2% range, occasionally dipping below 1%, and recently rising above 2%.

Over the previous 6 years, unemployment has fallen from 8% to 3.7%. Inflation has mostly stayed in the 1% to 2% range, occasionally dipping below 1%, and recently rising above 2%.

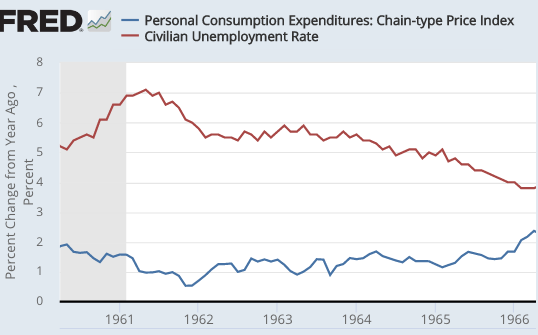

In contrast, here’s the picture as of mid-1966:

In this case, unemployment rose to a peak of 7% in 1961, then gradually trended down to 3.8% in mid-1966. Inflation mostly stayed in the 1% to 2% range, occasionally dipping below 1%, and recently rising above 2%.

In this case, unemployment rose to a peak of 7% in 1961, then gradually trended down to 3.8% in mid-1966. Inflation mostly stayed in the 1% to 2% range, occasionally dipping below 1%, and recently rising above 2%.

Hmmm, that sounds familiar.

I don’t expect the next 3 years to look anything like the late 1960s. But if we are to avoid a repeat of the 1960s, it will not be because the current situation is radically different from 1966, it will be because we take steps right now to make sure than the future situation is radically different. And that requires a dramatically less expansionary monetary policy that what the Fed adopted in 1966-69.

In the 1960s, the Fed tried to use monetary policy to drive unemployment to very low levels. Let’s not make that mistake again. Better to produce stable NGDP growth, and let unemployment find its own natural rate.

Tags:

11. October 2018 at 07:23

Very different demographics (huge cohorts entering, small cohorts leaving) and increasing female LFPR during the 1960s. I think this supports your view.

11. October 2018 at 07:50

Scott,

It seems to me like even in the market monetarist camp, there’s some disagreement. Lars Christensen (and David Beckworth to a lesser extent) seem to be saying current path of planned hikes will invert yield curve, maybe cause recession, maybe be too tight.

You, on the other hand seem to be saying things are going smoothly for the most part, and this post even seems to be hinting at the dangers of being too loose.

Do you see yourself at odds with those guys at all, or have you picked up on the same thing I’m mentioning?

11. October 2018 at 08:12

Sure, shoot for NGDPLT. Not a bad strategy.

But are the 1960s an analogy?

Big Labor, Big Steel, Big Autos. Tight regulations on all transportation. Anyone old enough remember the CAB? How about ICC? The FAA? The FCC? Telephone monopolies? Regulation Q? The USDA? Much less domestic competition, which allowed price increases absent demand. Much less global trade. (It is remarkable that such a regulated 1960s economy could grow so much, and deliver much higher living standards and higher real wages so rapidly.)

Besides which, inflation in the US in the 1960s topped out at 4.7% in 1969, and then fell to 2.8% by 1973. Read that again! There was no double-digit inflation in the 1960s, in fact there was not even 5% inflation in the 1960s (see first cite below). And inflation retreated in the early 1970s.

The 1970s inflation, which is what most people erroneously conflate with the 1960s, happened in the mid-late 1970s. By some measures inflation spiked to 10%, but by other inflation measures the US never even hit double-digits even in the 1970s (see second cite).

I think it was Luigi Zingales who said we have had two generations of econ Ph.D.s who earned their letters by writing calculus-strewn theses on how to beat inflation. Central bankers talk about little else.

In Australia, they have not had a recession since 1991, and the RBA targets 2% to 3% inflation. They had some stretches of 4% inflation. Big whoop, 4% inflation. Somehow they survived.

To sum up, “Inflation, shmaflation.”

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/JCXFE

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PCETRIM12M159SFRBDAL

11. October 2018 at 09:28

Keenan, I pay no attention to the current path of rate hikes expected by the Fed, I look at the market forecasts. Right now the markets are not forecasting excessive rate hikes, or any sort of recession. Look at the NGDP futures market.

I think they are saying that if the yield curve were to invert a recession would be likely. I’ve done lots of posts on that issue. The yield curve is a good predictor, but not a good indicator of whether money is too easy or too tight. And I’m not convinced that the yield curve is about to invert. We’ll see.

Ben, None of the factors you cite played any role in the 1960s inflation, which was 100% easy money, and 0% supply side factors.

11. October 2018 at 10:32

Scott,

I must miss your point, because NGDPLT is closer to optimal policy, so why not promote that? Within that framework, we can provide a bit more monetary stimulus without a 70s style loss of the anchor. I favor 5% NGDPLT rather than closer to 4% to try to make sure we’re not keeping people unemployed longer than necessary.

The 1960s and 70s is entirely irrelevant to the policy I want.

11. October 2018 at 10:37

An interesting parallel is also that Trump really *wishes* he had an Arthur Burns like Nixon had. The Fed will definitely not allow sustained inflation above 2%, but it’s a curious parallel nevertheless.

11. October 2018 at 10:42

Michael is correct that the targeting inflation rather than NGDP risks a worse recession. Early-90’s and early-00’s recessions had successful PCE targeting with NGDP growth too low.

NGDP prediction markets are short-term and illiquid. TIPS indicate 2% inflation and 1% real rates for 10-years, but those predictions don’t rule out lacking or uneven NGDP growth within those 10 years.

11. October 2018 at 11:19

Scott,

I would also point out that good monetary policy does not lead to the kinds of shocks we’ve seen over the past 5 trading days, unless it’s a corrective for very misguided previous policy. The Fed made a mistake in at least one direction recently, if not both directions.

They should just adopt NGDPLT and stop trying to anticipate inflation.

11. October 2018 at 13:58

Scott,

Question – Is there a reason you’re not using core inflation in the graphs? Not saying it’s wrong just curious. Any thoughts on which is a better guide for setting analyzing monetary policy. (I think the Fed uses core as their target

Also it looks to me like the Fed is still not adhering to their own target of 2%. It seems more to me that their target is around 1.75% and that they are treating the target as a cap rather than an average.

11. October 2018 at 16:05

Scott,

One more question….

What is the difference between a 5% NGDP target and a 6% NGDP target. Will a 6% target result in higher RGDP growth and higher inflation or will it just result in higher inflation.

11. October 2018 at 16:43

, None of the factors you cite played any role in the 1960s inflation, which was 100% easy money, and 0% supply side factors.–Scott Sumner.

Well… I suppose one can say inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.

On the other hand, imagine a country where the supply of developed property is limited by property zoning, leading to rises in residential rents. The higher rents feed into labor rates, and in fact you may find labor shortages.

Now, of course a central bank could keep money tight enough to prevent inflation even in this circumstance.

But this zoned economy could also “fight inflation” by getting rid of property zoning.

So is an inflation in a country defined by property zoning a result of monetary policy, or of overly tight property zoning?

George Selgin comes to this issue in another way, that you can have inflation in an agricultural economy when there is a crop shortage. In a crop bust, prices are higher even though monetary policy has been stable.

To be sure, every central bank operates in an economy that has structural impediments. But to say inflation is solely a result of monetary policy in a highly regulated economy is like saying a baby is solely the result of the male or the female in a mating act.

The 1960s economy was often defined by regulations which prevented new supply. A trucking company literally had to get a difficult to obtain license to serve two cities, for example.

Stockbrokers charged fixed commissions and could not compete on price.

If the supply-side can manipulate supply and price by appealing to regulatory authorities… Then maybe inflation is the result of a marriage between business and government, where central bankers validate the act.

11. October 2018 at 17:25

“Fed Is Intent on Raising Rates Even If Economy Sours

All FOMC members expect policy rates to rise above long-range estimates of what is considered neutral.

By Tim Duy Bloomberg

October 9, 2018,

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell is looking at monetary policy in a whole new way.

Recent speeches by Federal Reserve policy makers make clear that they have reduced their reliance on estimates of the long-run neutral level of interest rates as a guide for monetary policy. Going forward, market participants will need to more closely scrutinize the central bank’s Summary of Economic Projections for clues as to where rates may be headed.

Those forecasts currently point to a fairly hawkish path for monetary path. Not only do they indicate policy will eventually turn restrictive, but they also suggest policy will remain restrictive even as economic growth slows. In other words, the Fed doesn’t anticipate turning tail on their policy path even if the economy dips next year.”

—30—

Gadzooks!

You mean, this is a live proposition: the character we know as Trump may be right, and the entire combined intellectual firepower of the US Federal Reserve wrong, when it comes to pending monetary policy?

So, is the Fed “loco”?

Stay turned…same Bat channels, same Bat stations…

11. October 2018 at 18:05

Refining an earlier thought:

Suppose you have an economy where the supply side manipulates supply and price though captured regulatory agencies.

Then—as measured—would not inflation exist in a near-mechanical fashion, leaving a central bank with the option of “validating” the inflation, or plummeting the economy into contraction? And even in a central bank-induced recession, since the prices are fixed, the measured inflation would be the same?

In this situation, is measured inflation only a monetary phenomenon, or a marriage of state-regulated supply and monetary policy?

Of course, the 1960s was not a totally regulated economy, and supply-siders did not control price and supply through captured regulatory agencies in every sector. But large swathes of the economy were regulated.

So to say 1960s inflation was “100%” a monetary phenomenon…well, we can say only a male can trigger a pregnancy. Is the male the only reason you have a baby?

11. October 2018 at 18:32

dtoh,

Fed policy can only increase RGDP is there is slack in the economy, in the form of a demand shortfall.

11. October 2018 at 20:26

Michael, I doubt monetary policy has anything to do with the recent stock drop. Did the Fed make any announcements this week?

Stocks occasionally dropped even before the Fed existed.

dtoh, I was just responding to a comment. You could use core, and you’d get fairly similar results—inflation is gradually trending higher, albeit closer to 2%. I don’t think either type of inflation is a good indicator for monetary policy, but core is probably less bad. I don’t think the Fed is treating 1.75% as a cap. They are forecasting 2.1% inflation over the next few years.

Yes, a 6% NGDP target would give you higher inflation and the same RGDP growth as 5%. The only exception is during a brief transition period, where changing policy can move you away from the natural rate.

11. October 2018 at 20:31

@Benjamin Cole

That is really interesting info about inflation in the 60’s and early 70’s. Basically, it looks to me that inflation wasn’t a problem until 1973, which is the year that the oil embargo starts right? In which case, it makes me wonder if you can get really high inflation in the absence of a real shock or some really bad political climate/ management.

11. October 2018 at 23:03

Scott,

I think what’s happening in the market over the past 5 days is similar to what happened shortly after Greenspan was appointed in ’87. There’s a change in monetary policy regime underway and markets are concerned about the tighter money. I know you don’t think the Fed caused the brief crash of ’87, but I long have blamed them for it. That’s a very uncommon perspective.

However, that the market currently fears the Fed reaction function is the dominant view in financial media. That certainly doesn’t make it correct, but what real factors can you point to to account for the recent sharp sell off?

Yes, markets were volatile before the Fed, but then that was under an even less optimal monetary policy regime.

My argument is simply that we can stand some higher inflation, and adopting a 5% NGDPLT policy would give it to us, likely decreased monetary instability. If you want to argue for an NGDPLT at 4%, fine, but 5% is hardly different in the long run. I think the risk/reward balance is a bit in my favor

11. October 2018 at 23:17

By the way Scott, I believe I was claiming that tight money was keeping unemployment higher than necessary last year, and all we’ve seen is unemployment fall since, with very slight increases in inflation. Much of the inflation increase could be due to the FOMC stating that the 2% inflation target would be symmetric going forward, with rates allowed to exceed 2% for brief periods, with a 2% average over the longer term.

So, policy perhaps got a bit looser, but not loose enough. You stated you were surprised by how low the unemployment rate had gotten.

This doesn’t make me correct, but doesn’t it at least raise the possibility that I’ve been closer to correct than you’ve been lately. I day that with the full knowledge that you’ve forgotten more about monetary policy than I’ll ever know.

12. October 2018 at 01:51

I think most people are surprised that inflation in the 60s was so low.

So inflation in the 70s was all about exploding oil prices? That sounds like an interesting theory. Or as Arte Johnson would say: Very interesting but also stupid.

12. October 2018 at 03:54

P Burgos:

You are correct sir!

In fact, even with mediocre macro-management, inflation is not much of a threat.

Lots of great economic growth has coincided with moderate rates of inflation, in the 5% or under range.

Want another amazing fact?

In Q4 1965, the real GDP was up 8.5% year-over-year. It was full-tilt boogie boom times in Fat City.

And despite the inflationary structural impediments I mention above—the ability of the supply side to control price and supply through captured regulatory agencies—inflation never got above 5% in the 1960s.

We had good solid real GDP growth in the 1990s also, with even lower inflation that the 1960s.

If you want to cry yourself to sleep, think about the trilions upon trillions of dollars of lost output in the last generation, due to the Fed’s peevish fixation—nay, manic obsession—with inflation.

And I put it mildly.

12. October 2018 at 06:38

Scott,

You said, “Yes, a 6% NGDP target would give you higher inflation and the same RGDP growth as 5%.”

If that’t the case, what’s the point of targeting NGDP. Why not just target inflation. Because if what you’re saying is true, NGDP is perfectly correlated with inflation. You can unambiguously specify any NGDP target just by specifying an inflation number target.

12. October 2018 at 07:37

Burgos, CPI inflation rose to 6% in 1969, was artificially held down by wage/price controls in 1971 and 1972, then exploded in 1973-74 when the controls began being phased out.

So no, the inflation problem did not start in 1973.

Michael, Yes, I did not expect unemployment to fall so low, but then I did not claim money was too easy last year. In past years I was mostly saying it was too tight, due to undershooting the 2% target, while more recently I’ve thought it was about right. So while I was wrong about unemployment, I don’t think I was wrong about policy. I’ve never claimed to be able to predict changes in the natural rate of unemployment, nor do I think the Fed should even target unemployment. That’s not so say that an unemployment target might not be effective in a given year, and your advice might have been right. But it’s like stock picking, eventually you will be wrong, and that will destabilize the economy.

dtoh, I meant same average RGDP growth rate, the cyclical behavior would be less stable with inflation targeting. You’d have more years of a depressed labor market, and fewer years at potential.

The way you worded your question I thought you were referring to long range trends. I do concede that suddenly switching to 6% would provide a quick boost, but at the cost of greater cyclical instability down the road. That’s what went wrong in the 1960s, among other things.

12. October 2018 at 08:47

Scott,

Yes, I wouldn’t claim to be able to reliably identify loose versus tight monetary policy under most circumstances. There simply isn’t much data upon which to draw such conclusions in cases like the present one.

12. October 2018 at 14:05

Scott,

Agree on stability. That was the answer I was expecting

I think though that even if you look at averages, the split between inflation and RGDP is not a step function. If you’re correct and if the NGDP target is set anywhere at or below the natural RGDP rate, then there will be zero inflation. If the NGDP target is above the natural rate, then inflation will exactly equal the difference between the NGDP target and the natural RGDP rate.

That would be true if the economy were monolithic… but it’s not. Some sectors of the economy have higher and lower natural rates. So as a result when you aggregate the sectors, you will still get some inflation even if you set the NGDP target below the natural rate, and …. setting an NGDP target above the natural rate will still buy you some extra growth (even when looked at from a long term average.) Looked at another way, inflation as a function of the NGDP target is a curve not a straight line.

So what interests me is where you optimally set the NGDP target relative to the natural RGDP rate in order to maximize utility. At what point does the dis-utility of inflation offset the benefit of the higher output.

BTW – I think you will probably counter-argue that my argument is wrong because over time the flow of capital and labor will offset any sectoral difference in the economy and therefore in aggregate RGDP will always trend back to the natural rate. I don’t think that’s correct because the economy is always changing rapidly enough that capital and labor will never catch up.

12. October 2018 at 19:18

P Burgos/Scott Sumner:

Of course, there are different indices of inflation. Most economists look at “core” inflation rates, and the Fed now uses PCE core as its peg on inflation.

Citing the CPI headline rate for a month or two in the 1960s is probably not the right way to measure inflation.

Okay, so let’s look at monthly PCE core inflation rates, but year-over-year:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PCEPILFE

We see inflation never gets above 4.8% in the 1960s.

Even the headline CPI topped out at 5.9% in Dec. 1969.

I am not advocating for double-digit inflation.

But the Fed’s current squeamish hysteria regarding inflation ii the 3% to 4% range is not a good idea either.

BTW, I am a supporter of Scott Sumner and the Market Monetarists’ idea that a Fed should target NGDPLT, though I probably would pick a higher target than most.

The idea of an NGDPLT target band is more appealing–say 5% to 6%.

Why?

Central bankers can be trusted to turn any target into a ceiling, and then any ceiling into a “do not approach, danger zone.”

If the Fed adopts a 4% NGDPLT, then that will become a ceiling, which means the real target is, say, 3.4% NGDPLT. Indeed, 3.5% may become the working ceiling.

Fine and dandy, the Fed has shown in can beat inflation. It has been doing that for decades. Beating inflation turns out to be easy to do, which is another reason central banks want that to be the metric. No one wants difficult hurdles.

But managing an economy is about maximizing prosperity (which usually means leaving free markets alone).

Inflation, schmaflation. There are much bigger fish to fry.

12. October 2018 at 20:02

Add on

It is probably true that the real growth rates of the 1960s, or even of the 1990s, cannot be replicated in the next 10 years, due to demographic changes.

But it is also true that if real wage gains begin to show some punch, we will likely see investment in plant and equipment that will punch up the productivity numbers. Thus, more real growth.

This may already be happening, although for now we may just be seeing economies of scale against fixed costs improvements in productivity. The good stuff may be ahead.

One thing seems indisputable: US-based corporate profits are at or near all-time record highs, both relatively and absolutely.

When I say I want “full-tilt boogie boom times in Fat City”—well that is where we are already in terms of corporate profits. It has never been better than this, and it is much, much better than even the Reagan days. See:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CPATAX

Corporate America is awash in green. It stands to reason if labor begins to cost more in the US, we will start see floods of capital go into productivity improvements (unless multi-nationals simply offshore labor).

If the Fed does not asphyxiate the economy, some really great things could start to happen. Automated warehouses, new and better factories of all types.

Self-driving tractors for farms are already a thing.

We are on the cusp of commercially viable battery cars, and decreases in oil consumption.

The Fed should stand aside.

12. October 2018 at 22:41

Michael Sandifer:

Stocks can be volatile upwards as well as downwards. Why have US equity markets markets been so out of line with the RoW this equity markets this year?

Scott:

Am wondering when you will start talking about Monetary Offset again? Remember that? The Fed is duty bound to offset the total failure of the Tea Party deficit hawks inside the GOP.

12. October 2018 at 23:27

https://www.aei.org/publication/facts-and-falsehoods-about-the-us-labor-market-a-long-read-qa-with-adam-ozimek/

The above is a terrific interview with Moody’s economist Adam Ozimek. He has some great insights on unemployment, and the short story is there still is substantial labor slack. A lot more people are on the sidelines than ever before, but are not being measured.

Ozimek even concludes by advocating for a national property tax!

AEI scholar James Pethokoukis does a great interview.

There are some shafts of light in macroeconomics-land!

13. October 2018 at 01:30

James Alexander,

The stock market returns this year reflect a combination of the expected effects of tax cuts, monetary policy, tariffs, and higher earnings due to higher economic growth.

13. October 2018 at 01:51

P Burgos:

To answer your question about oil, yes oil prices exploded in the 1970s.

https://www.statista.com/statistics/262858/change-in-opec-crude-oil-prices-since-1960/

We see oil was $1.27 a barrel in 1969 (I know, hard to believe) and then $35.52 in 1980. This happened to an economy drunk on the cheap stuff. Demand for oil tends to be inelastic in the short-run, and more so the longer out you go. (OPEC oil prices averages, btw)

Interestingly, there was another run-up in oil prices from 2002-2012, from $24.36 to 109.45. But this time around, the use of oil per GDP unit was way down.

The US economy is not as inflation-prone as in the 1970s. And I don’t wear bell-bottomed pants anymore. Those bell-pants must be still the rage inside the Fed. Judging from their outlook.

13. October 2018 at 05:52

The difference between a growth rate target and LT is LT can’t turn into a meaningful cap. A Fed with a 4% growth rate target may be content turning in 3.4% year after year. But if the target is 4% NGDPLT, the expectation is that NGDP will be 48% higher in 10 years. People will notice if NGDP is only 39.7% higher. The misses compound under LT.

13. October 2018 at 09:56

Michael Sandifer you asked: “why the stock sell off?” Those reasons for the rise being marginally reversed is a good starting point.

One caveat, tariffs are a rise in taxes and are thus anti-growth. Also, Trump’s attack on the Fed was destabilising. He’s partly getting his retaliation in first as the Fed are duty bound to offset his and the GOPs crazy, pro-cyclical, deficits.

I ask again, though, where is the Tea Party, retired, looking the other way, dead? Where is the new Nuke Gingrich et al? That rising debt to GDP ratio, from already peacetime record levels should be an outrage to that hypocritical crew.

13. October 2018 at 10:46

James Alexander,

Hypocritical is definitely the word. It frustrates me no end that Republican political commercials are getting away with calling Democratic candidates irresponsible, when the main Democratic “offense” is mostly wishful thinking that life could somehow return to normal. Whereas the present Republican hidden agenda, is purposely and irretrievably irresponsible.

13. October 2018 at 11:38

dtoh, I don’t agree with your premise that setting the NGDP trend rate below the RGDP natural rate gives you zero inflation–it gives you deflation.

“At what point does the dis-utility of inflation offset the benefit of the higher output.”

That depends on the rate of taxation of capital income. The lower the tax rate, the higher the optimal NGDP growth rate. When you tax capital income, raising the NGDP growth rate is equivalent to raising the real tax rate on capital income. But it’s less of a problem when the NOMINAL tax on capital income is low.

We don’t know exactly where the optimal NGDP growth rate is—it’s guesswork.

I usually mention 4% because I think it’s close to optimal, and politically acceptable. But I’d be fine with 5%, and even 6% would not be that bad if made into level targeting. But it would be very hard to get political consensus for 6%. The GOP would revolt.

James, If the Fed targets inflation at 2%, they are doing monetary offset. If inflation rises above 2% on a sustained basis, then they have failed to do monetary offset. We will see.

13. October 2018 at 13:49

Scott,

You said,

“I don’t agree with your premise that setting the NGDP trend rate below the RGDP natural rate gives you zero inflation–it gives you deflation.”

If sticky wages and prices didn’t exist that would be true, but if sticky wages and prices didn’t exist, you wouldn’t need monetary policy.

Look at the FRED graphs in you post. Inflation never goes negative.

13. October 2018 at 23:46

Scott,

So, hopefully we can get past references to the 70s now when I say I think unemployment has a ways to fall. All I want is a 5% NGDPLT, which I think we all agree could anchor inflation at slightly higher rate for very little cost.

Inflation targeting is suboptimal and I prefer not to discuss monetary policy within a suboptimal regime, even if it happens to be the current regime.

14. October 2018 at 11:58

dtoh

“If sticky wages and prices didn’t exist that would be true, but if sticky wages and prices didn’t exist, you wouldn’t need monetary policy.Look at the FRED graphs in you post. Inflation never goes negative.”

I’ll propose Japan as a counter-example. Low NGDP leads to sustained deflation:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=lAiw

14. October 2018 at 15:00

dtoh, Actually, CPI inflation went slightly negative in 2009, but you are right that it doesn’t go sharply negative. But that is only partly due to sticky prices. There are dozens of examples of deflation during previous decades, sometimes rapid deflation (1921, 1929-33, etc.) The reason you don’t see much deflation in recent decades is because Fed policymakers adjust policy to prevent it from happening.

Sticky prices do not imply a price level that cannot fall over time, just that inflation falls more slowly than NGDP when the trend rate is lowered. If trend NGDP is below trend RGD for a sustained period, then prices will fall.

Also, see LK’s comment.

Michael, There’s a big difference between “what you want” and “what the Fed should do right now assuming they reject your proposal and stick with a 2% inflation target”. That’s my point. I obviously have no objection to the Fed setting a 5% NGDP target. I have a big objective to them setting a 2% inflation target, and then missing in a procyclical fashion.

14. October 2018 at 18:29

Scott, LK Beland,

I agree that sticky prices/wages is behavior that CAN be changed, but…. it takes a long, long time and the cure is worse than the disease. Japan is good example. 30 years of stagnation and while there has been some deflation, wages are still very sticky on the downside. Also, it’s created new price stickiness on the upside, which is not good for the economy either.

The fact of the matter is that sticky wages/prices exist in the U.S. economy, and therefore it is inescapable that when an NGDP target is set above or below the natural RGDP rate, then it will effect not just inflation/deflation, but it will also effect RGDP.

Put another way, up to a point a higher NGDP target will buy you a little extra real growth. This seems incontrovertible so the question remains, where to set the NGDP target to maximize utility. At what point, does the dis-utility of inflation outweigh the higher real growth.

If you believe that enacting a monetary policy based on an NGDPLT is more than a topic for academic debate, then this is a practical issue which needs to be addressed.

Scott, BTW core inflation only went negative for one quarter in Q4 2008 (not 2009) and then that was only with RGDP plummeting at something like -8%.

15. October 2018 at 16:37

dtoh, I generally agree with that, but I don’t think it has much to say about NGDP trend growth of 4%, vs. 5% or 6%. That’s fast enough to avoid the sticky wage problem (I don’t regard sticky prices as a big problem for changes in trend NGDP, just wages), but I concede that trend NGDP growth can be so low that it runs into the problem of money illusion—workers don’t like nominal wage cuts. Perhaps Japan had that problem in the 1990s and early 2000s.

And I agree with you that it’s an empirical question, as increases in trend NGDP have pros and cons. I just think that once you get beyond roughly 4% per capita, the cons clearly outweigh the pros, but only slightly for 5% or 6%. Interestingly, George Selgin prefers a much lower rate than I do.

16. October 2018 at 00:01

Scott,

I think it depends a little on what you think the natural real growth rate is. As you know I believe the tax changes will have a larger and more permanent effect than you. Other posters have mentioned technological and societal changes perhaps auguring for higher growth.

It would seem to me that if there is at least some chance that the natural rate has risen, then it would be better to find that out and suffer a little inflation, rather than not finding because the target for NGDP has been set to low.

16. October 2018 at 06:58

I suspect that I am wrong about this, and maybe someone will explain why, but I think that a higher NGDP growth rate would have a positive impact on real GDP growth. The theory is that that higher inflation, up to a certain point, allows for quicker changes to relative prices, and hence quicker reallocation of real resources across the economy. That is the theory; is there empirical research showing that there isn’t stickiness in prices for things like consumer products, real estate, and capital goods? I am thinking that if there is some downward stickiness in those things, a NPDP growth rate that allows for inflation to regularly be between 3-4% might bring extra economic output not just when the monetary regime transitions to an NGDP level target, but would also bring extra growth even compared to an NGDP level target with a lower NGDP growth rate. I certainly think that a higher NGDP growth rate, as opposed to a lower one, will help with us avoiding having too many homeowners underwater for long spells of time (and hence preventing them from moving to another metro).