Next stop, Stockholm?

Back in August just about everyone was pessimistic about the economy, including me. I’m still pessimistic, but markedly less so than a few months ago. Recent numbers from both the asset markets and the real economy point to slightly faster than expected growth going forward. For instance, weekly unemployment claims have recently fallen quite sharply, which suggests that the recent drop in the unemployment rate may not be a fluke. Of course we need to keep in mind that this “recovery” has already gone through several phases that proved quite misleading. But let’s say it’s true that growth is picking up; what could account for this?

My hunch is that I misjudged the Fed move back in August, when they promised low interest rates for the next two years. That seemed pointless without making the promise condition on some sort of nominal growth target (GDP or inflation.)

Now there are indications that the Fed may do just that at the January meeting. At that meeting the FOMC is likely to be considerably more “dovish” than the current FOMC (where three of the four floating seats are filled by hawks.) Bernanke probably thinks it’s a good time to go on record with future policy intentions, and will be able to reassure markets that the Fed won’t make the same mistake as the BOJ and ECB made. Recall that those two institutions twice tightened prematurely, and then soon after had to do humiliating about faces and cut rates again. Central banks don’t like doing that, which shows just how bad the tightening errors were. (The BOJ did this in 2000 and 2006, the ECB in 2008 and 2011.)

If the press chatter is correct, Bernanke will promise to avoid the mistakes of the BOJ and ECB, he’ll promise to keep rates low as long as it takes to get a decent recovery (by his criterion, not mine.) This will be done by combining interest rate and economic forecasts, which will allow readers to discern implied policy feedback rules. At least that’s what I think is going on.

If I’m right, and if it works, then Michael Woodford and Lars Svensson might come out of this as heroes, not we market monetarists.

But this policy will still be too little too late. I still say they should promise to buy securities until they expect NGDP growth of 6% to 7% over the next few years, and something like 4.5% thereafter. That won’t happen. But if I’m not mistaken, even this policy will help somewhat. More than I thought back in August, when the promise seemed too vague to have any impact. I misjudged the fact that there probably always was an implied conditionality in the interest rate promise.

Of course if the eurozone blows up . . .

[BTW, the title of this post refers to the Swedish Riksbank, which has been doing this sort of signaling for years.]

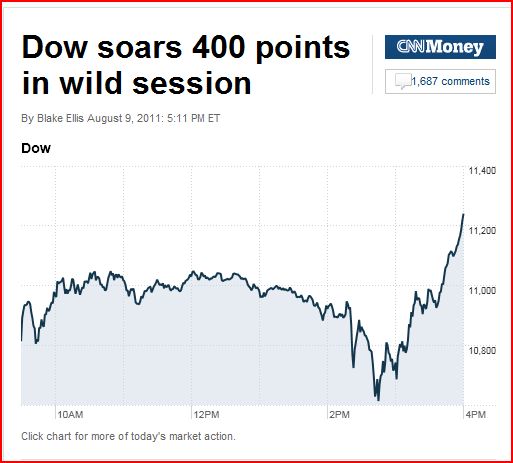

It’s interesting that it took me so many months to have second thoughts about my negative verdict on the policy last August. Equity investors seemed to need only about 30 minutes to figure this out (after the 2:15 announcement.)

BTW, if they make the path of the fed funds rate conditional on demand, then there will no longer be any doubt about whether monetary policy is at least partly offsetting fiscal policy.

PS. And kudos to Karl Smith, one of the few people that didn’t seem pessimistic a few months ago. BTW, here’s a good Karl Smith post on this general topic.

Tags: Sweden

22. December 2011 at 10:02

Scott I´ll just say: If you were too pessimistic in August, you are overly optimistic now. And the stock market has been doing that “trick” everytime “positive noises” emanate from the FOMC (or even EZ summits). And they never last long!

22. December 2011 at 10:07

Marcus, Maybe, but as I said in the second sentence I’m still pessimistic in absolute terms. I just no longer expect the economy to get worse. I think it will get better very slowly.

22. December 2011 at 10:09

I believe the August statement was the third great policy error of the Bernanke era. The first was holding money growth to a barely positive level in 2005, 2006, and 2007, an error which caused the Great Recession. The second was allowing money growth to prematurely fall to low single digits from mid-2009 to mid-2010, which caused a dangerous deceleration in the rate of recovery. The third was this imprudent implied promise to hold to ZIRP for two more years when money growth had already re-accelerated to a generous rate. I very seriously doubt that the ZIRP promise will survive 2012 before being broken.

22. December 2011 at 10:12

OK. But Woodford and al will not come out as heroes. Bernanke is not doing anything to “kill” the economy, giving it just enough “juice” for it to stay alive and “heal (very slowly so as not to get an “inflation fever”)on its own.

Imagine the new President who will be sworn in a little over a year from now “changes the team”. And the new team switches to NGDPT and things began to improve immediately…

22. December 2011 at 12:33

Scott, you are assigning too much importance to the August meeting. It was not that pivotal and I’ll tell you why.

First, the market reaction is much more ambiguous than you think. I remember that day clearly and the initial market reaction after the FOMC statement was a big crash (treasury yields also dropped precipitously at that time) because the promise to hold rates low was interpreted to mean that the economy would suck until at least 2013. After a bit of reflection, the market changed its mind and decided that maybe monetary policy was changed in a good way and ramped up into the close. The next day was more of the same (market crashed early, ramped up in the middle of the day, and then crashed toward the close). The market didn’t know what to think.

The best explanation for the slightly improved economy right now is: (1) liquidity injections by the Fed and ECB, (2) seasonality (the economy is almost always better in the winter), and (3) employment is dropping slowly because the small amount of income generated by the anemic growth is being used to hire more people rather than increase the wages of those that are already employed.

We’ve seen this before in 2008. The Fed and Congress came up with all kinds of schemes to increase liquidity for banks, etc. However, nothing really changed until the Fed actually printed money. The market was at its bottom in 2008 shortly before the Fed announced QE1 and was at its bottom in 2009 shortly before the Fed expanded QE1.

The recent liquidity injections will keep European banks from going under for quite a while, but they won’t do anything to actually fix the crisis. In fact, they are really making things worse. In the recent LTRO conducted by the ECB, Italian banks borrowed money using collateral consisting of bonds they issued to themselves, which were guaranteed by the Italian government (the Italian government guarantee was necessary for the ECB to accept it as collateral). This will not end the European banking crisis. It only serves to dial it up even more.

The only way to fix things is to print money, plain and simple.

22. December 2011 at 12:46

hard to say if it will get worse. this recession recovery has been punctuated by one or two periods of spurt growth, so its too early to tell. Italian bond yields have been slowly creeping up to 7% in spite of the ECB back-door QE yesterday (what, no one noticed this??), with inflation expectations declining (5 yr back down to 1.6%, lower than august). It’s a sad day when treading water makes people feed less pessimistic. The Fed has successfully lowered expectations to the point where merely not having a full blown financial panic makes people feel optimistic.

22. December 2011 at 12:47

http://www.bloomberg.com/quote/GBTPGR10:IND

22. December 2011 at 13:02

Stephan, I’m pretty sure it will survive 2012, the question is whether (as in Japan) it will survive 2020.

Marcus, I’m not saying Woodford would deserve to be a hero, just that he’d be portrayed that way.

Scott, You said;

“First, the market reaction is much more ambiguous than you think. I remember that day clearly and the initial market reaction after the FOMC statement was a big crash (treasury yields also dropped precipitously at that time) because the promise to hold rates low was interpreted to mean that the economy would suck until at least 2013. After a bit of reflection, the market changed its mind and decided that maybe monetary policy was changed in a good way and ramped up into the close. The next day was more of the same (market crashed early, ramped up in the middle of the day, and then crashed toward the close). The market didn’t know what to think.”

How can I be misinterpreting it when my interpretation is identical to yours?

Seasonality can’t explain the data because all the data is seasonally adjusted.

dwb, I agree. As I said, I’m pessimistic.

22. December 2011 at 13:15

Scott S, we’ll know whether the promise survived at this time next year. I have placed my real-world bets on rising rates and the past month’s experience indicates others trading Eurodollar futures, specifically the TED spread, seem to agree:

http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/quote?ticker=.TEDSP:IND

And, Scott N, please note: the S&P 500 closed at 1119.46 on 8/8/2011, the last trading day before the ZIRP promise. Today it cosed at 1254, a gain of 12%. That is a significant move and should not be ignored.

22. December 2011 at 14:10

Scott, I interpreted your comment to mean that the market conclusively decided that ZIRP through 2013 was a good thing. I think the follow through the next day showed it didn’t.

Seasonality doesn’t explain all the data. It is only the second factor on my list. I think the central bank liquidity interventions have done much more. Even with that, the seasonality adjustments are pretty much voodoo with the end result being that the economy almost always seems to be doing better in the winter than the summer.

Stephen, note that the S&P hit an intraday low of 1078 early on 4 October 2011. So from the August Fed meeting until then, the market dropped. By the way, what happened on October 4th? The Bank of England announced additional QE and the ECB announced additional liquidity measures. If we are going strictly by the stock market, then it would seem that the cause of our improved economic situation stems from this and not the August Fed meeting.

22. December 2011 at 15:57

Scott N, the early August and early October lows were a double bottom. I wouldn’t contend that equity prices (and certainly not two months of sideways price action) are the sole arbiter of whether monetary policy has been too tight or too loose for that would make it difficult to explain the 1970s or the 1950s or 1932-37 etc. However, you seem to have been arguing that the rise in stocks under ZIRP has been more ephemeral than has been the case.

I actually agree with you if you’re saying that quantitative easing has been an explanatory variable in the rise in stocks and the improvement in economic activity. That dynamic is central to my expectation that the ZIRP promise was unwise and is nearly sure to be broken: to hold Fed Funds near zero would require the FOMC to continue buying securities and expanding the Fed’s balance sheet. Do you think they are inclined to do so with initial unemployment claims at a three year low and retail sales growing nearly eight percent per year? Far better and more likely they will say sometime in 2012 “Oops, we were wrong. Time to put rates higher. But isn’t it wonderful that jobs are being created and the end of the world has not yet arrived!”

22. December 2011 at 21:48

You know what Scott? The last time I was this confused by the behavior of another human, I was trying to get a date for the prom.

It seems like you are saying in this post, “Based on the developments in the economy in the last few months, the Fed has actually been doing a better job than I predicted it would, back in August.”

But I thought that was exactly the kind of non-EMH analysis you specifically DON’T do.

So help me out, you nuanced little minx.

23. December 2011 at 06:59

Stephen, I hope you are right.

Scott, You said;

“I interpreted your comment to mean that the market conclusively decided that ZIRP through 2013 was a good thing. I think the follow through the next day showed it didn’t.”

I certainly agree the market was uncertain, that’s why it was so erratic after the annoucement. First it thought it was bad news, then good–that indicates a high degree of uncertainty.

I strongly disagree on seasonality, I don’t know where you get that idea. Can you cite a study?

Bob, I don’t understand your question, what does the EMH have to do with this post? The EMH does not imply that the world is not full of uncertainty. People and markets change their minds all the time.

24. December 2011 at 20:27

Scott, I don’t remember the exact post, but when it came to evaluating QE2 (I think, maybe it was QE1), you quoted somebody like Tyler Cowen who was talking about what the world would have to look like *after the fact* for us to know, in retrospect, if QE2 had worked. And you said that this is not at all how you do things. Rather, you said we’d know the day of the announcement whether it worked or not, and your reasoning involved the EMH. I think you used an analogy like steering a ship or something too. (I’m not talking about your more recent analogy with the FOMC going to New York or whatever.)

So now, in this post, you seem to be reverting to the commonsense view that the Fed does something, then we wait and see if works or not. Hence my confusion.

25. December 2011 at 09:19

Bob, I favor having the Fed control NGDP expectations, so that’s the way to judge if something works. If things later do better than was expected, it might be because the market was wrong, or because the Fed did additional things. In this case the additional things would be further explicit signals about future policy intentions.

But let’s take the worse case for me, if nothing additional was done and it just turned out better than expected. I’d use an analogy from blackjack. If I’m not mistaken, calling for one more card when you already have 20 points is an objectively bad move. If the extra card turns out to be a ace, then it means you win. But I’d still say the decision to call for an extra card was objectively bad, you just got lucky. I hope that explains the distinction I am trying to make for monetary policy. I want it to be judged as to whether it is a good move based on what we know at the time.