It’s not structural, and it wouldn’t matter if it was (pt. 2 of 2)

It didn’t take Andy Harless long to figure out what part 2 of this essay would look like. Here’s his comment to part 1:

At the risk of giving away the punch line: structural unemployment is pretty much the same deal as an oil shock; it’s a reduction in aggregate supply. In both cases, employment eventually readjusts: in the structural case, because workers get retrained, relocated, &c; in the oil shock case, because product prices and productivity rise faster than wages so as to re-establish profit margins. In both cases, the adjustment happens faster if monetary policy accommodates: because there is more incentive to retrain and relocate workers; or because product prices rise more quickly.

The bottom line is that the Fed had been delivering 5% NGDP growth for decades, and no matter what caused the current crisis, they needed to continue delivering 5% NGDP growth. This means that money has been far too tight since August 2008, even if most of the unemployment is structural. I am reacting to statements like this from Narayana Kocherlakota:

Monetary stimulus has provided conditions so that manufacturing plants want to hire new workers. But the Fed does not have a means to transform construction workers into manufacturing workers.

There are so many things wrong with this that I hardly know where to begin:

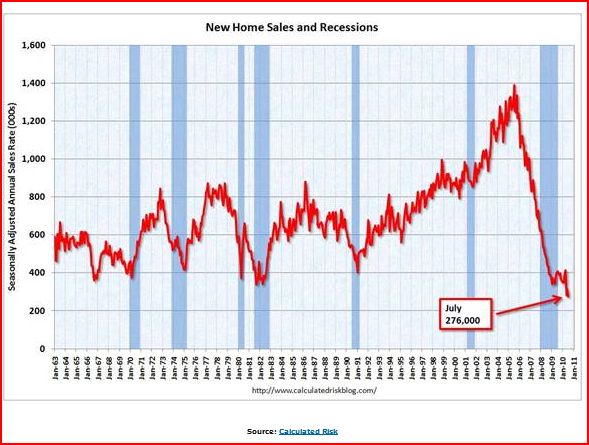

1. The structural theory is usually based on the fact that the housing bubble caused residential housing to become severely overbuilt by 2006, necessitating a sharp decline in construction jobs regardless of what the Fed did. That’s true, but as this graph shows, almost all the decline in housing occurred BEFORE the severe phase of the recession started in August 2008. (Almost halfway through the blue vertical band that starts in December 2007.) So there was a structural loss of jobs after mid-2006, but it has little to do with the sharp rise in unemployment that only began two years ago.

2. The sharp loss of jobs that did begin in August 2008 was associated with three areas mostly unrelated to sub-prime housing; manufacturing, commercial construction, and services. All three of these turned down sharply precisely when NGDP started falling, i.e. when money got ultra-tight.

3. The problem is not struggling with the re-allocation of construction workers into manufacturing, as manufacturing has also shed lots of jobs.

4. It’s really not that hard to transform construction workers into factory workers. For God’s sake in WWII we put housewives into factories! And the average construction worker is far more skilled with heavy machines than the average housewife.

5. The Fed has not provided the monetary stimulus required so that factories want to hire workers. Volcker provided the monetary stimulus for factories to want to hire workers when he engineered 11% NGDP growth at an annual rate for the first 6 quarters of recovery in 1983-84. We’ve been running 4% NGDP growth in the first 4 quarters, and we are now downshifting to 3%. How can you get the 7.7% RGDP growth of the earlier recovery if NGDP is growing 3%? Are we going to have a minus 4.7% GDP deflator? When has an economy ever boomed with 5% deflation? People who ask why the economy should not yet have adjusted to 1% inflation are asking completely the wrong question. Even if we had adjusted, it would take 8.7% NGDP growth to get a Volcker-esque recovery. It’s simple math. What you are really asking is why isn’t inflation falling even further. That’s a tougher question. The 40% jump in minimum wages, and the 99 week unemployment extension probably made labor markets a bit less flexible that usual. But overall what we are seeing is not that far out of the normal. Both real GDP and inflation fell, with RGDP falling more sharply. That’s pretty normal for steep recessions.

Now let’s return to Andy’s point. Almost everyone agrees that the SRAS is upward sloping, even my critics. After all, my critics claim the Fed blew up the housing bubble with easy money in 2003, and that can only occur if money is non-neutral. This means that even if 100% of the current unemployment problem is structural, it is still true that monetary stimulus will boost employment. And since inflation is still below target, and expected to remain below target, monetary stimulus would also improve the inflation situation. It’s a win-win. So when people say that structural problems argue against monetary stimulus, they aren’t just wrong, they are doubly wrong.

Part 2: Stop searching for the Holy Grail of macro

Since David Hume, every bright young economist seems to want to take a stab at the problem of why nominal shocks have real effects (i.e. why the SRAS slopes upward.) They’ve all failed. It’s not that they haven’t come up with explanations; they’ve come up with plenty. Bennett McCallum once listed ten versions of price stickiness. Then there is wage stickiness. And misperceptions. And money illusion. And that’s ignoring how the supply-side intersects with nominal shocks, as when governments extend UI to 99 weeks during recessions.

They sift through all sorts of micro-level data, develop macro stylized facts, and then try to connect them up with theory. But they never get anywhere. Maybe all theories are true to some extent, and the relative importance of each effect varies from one business cycle to another. Milton Friedman once said that in 200 years we’ve only gone one derivative beyond Hume. (We look at changes in inflation, rather than changes in the price level.)

So I get pretty discouraged when I read economists trying to sift through micro-level data about prices and labor markets, searching for the Holy Grail of the micro-foundations of recessions. Hume explained our recession 200 years ago:

“If the coin be locked up in chests, it is the same thing with regard to prices, as if it were annihilated.” David Hume “” Of Money

That’s right; Hume knew that if the Fed paid interest on bank reserves, encouraging them to lock up excess reserves, it was like a contractionary monetary policy. Fed presidents would be better off spending more time reading Hume, and less time sifting through micro data that supposedly disproves “the” Keynesian model (as if there’s only one!) The brightest minds of the profession have attacked the problem for 200 years, and they’ve all failed. It’s a black box. It is truly the Holy Grail of macroeconomics.

Please stop searching for structural patterns, and start boosting NGDP growth.

(PS: I do agree that Obama’s economic policies are considerably less pro-growth than Reagan’s, but we could still be doing much better than we are. “There’s a great deal of ruin in a nation.” And again, those policies do not excuse the Fed allowing NGDP to suddenly fall 8% below trend.)

Tags: Structural Employment, Volcker recovery

27. August 2010 at 07:00

Not so, says S Williamson. Where you see a “cow ready for slaughter” SW sees a “stone from which more blood cannot be squezzed”!!!

http://newmonetarism.blogspot.com/2010/08/what-about-recovery.html

27. August 2010 at 07:06

“It is not by augmenting the capital of the country, but by rendering a greater part of that capital active and productive than would otherwise be so, that the most judicious operations of banking can increase the industry of the country.”

– Adam Smith

Soctt, Adam and I agree with you and David on IOR. But, rendering the grater part of the capital active just requires SUPER CHEAP HOUSES.

We don’t need factory workers. We need specialized $13 an hour employees, and even then it’s probably only $10 per hour because of price supports of health care and minimum wage, you really can’t print enough money to overcome those costs.

I repeat, you cannot print enough enough money to make factories suddenly pay $13 per hour for non-specialized labor.

By specialized we mean trained for unique production lines.

And unlike blindly printing $1T – SOLVING for training is EASY:

1. Force 26 weeks unemployed to take any job training offered by any employer – or they lose unemployment. Do not pay them until they are done with training. Set some time limits.

2. Require employers to hire only 1/3 of the potential employees they train.

Let companies write off all costs associated with training.

—–

Look, Bill Clinton hobbled by the deficit delivered the best structural gains this country could ask for at the time: Balancing the budget and Ending Welfare as we know it.

We need Obama hobbled by the deficit so he can deliver same: balancing the budget and ending employment as we know it.

Scott, you need to stop calling it “targeting NGDP” – you need to start calling is a “4% annual tax on savings.”

$100 in 5 years = $81

There are EASY solutions only made untenable because of liberals, stop pretending your system does anything other make their lives easier.

27. August 2010 at 07:27

David Stockman goes medieval on Sumner, stands shoulder to shoulder with me:

http://articles.moneycentral.msn.com/news/article.aspx?feed=MY&date=20100819&id=11912826

27. August 2010 at 07:30

Scott,

You wrote:

“3. The problem is not struggling with the re-allocation of construction workers into manufacturing, as manufacturing has also shed lots of jobs.”

Actually since December 2007 (when unemployment was only 5%) manufacturing has shed more jobs than construction. Krugman noted the cluelessness of Kocherlakota’s statement on Tuesday:

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/08/24/hangover-theory-at-the-fed/

I found Kocherlakota’s entire speech to be deeply disturbing. I was gratified to see that Krugman, Delong, Thoma, Rowe, Harless and yourself (I’m sure I’ve left out many more) feel the same. It’s a shame that the Fed appears to be full of seemingly intelligent people who almost never consult reality and instead mechanically invoke mathematical equations without truly understanding their context.

P.S. PhD proposal defense is now successfully behind me. (Phew!) Now I have to change direction and invent a new course on monetary policy in record time. (Class starts Wednesday!)

27. August 2010 at 07:32

From NYT–Sumner is ascendant?

Bernanke Signals Fed Is Ready to Prop Up Economy

By SEWELL CHAN

Published: August 27, 2010

JACKSON HOLE, Wyo. “” The Federal Reserve chairman, Ben S. Bernanke, said Friday that the central bank was determined to prevent the economy from slipping into a cycle of falling prices, even as he emphasized that he believed growth would continue in the second half of the year, “albeit at a relatively modest pace.”

To help sustain the economy, Mr. Bernanke gave his strongest indication yet that the Fed was ready to resume its large purchases of longer-term debt if the economy worsened, a move that would add to the Fed’s already substantial holdings.

27. August 2010 at 07:57

Reinhardt expresses some deeps insights about Scott:

http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/08/27/when-value-judgments-masquerade-as-science/

At least Krugman admits he’s not an economist, he’s simply the conscience of the liberal.

27. August 2010 at 08:20

Why can’t we turn the construction workers back into whatever they were before we turned them into construction workers?

27. August 2010 at 09:13

As long as I’m ranting about Kocherlakota, he did have one seemingly good point in that speech:

“Beginning in June 2008, this stable relationship began to break down, as the unemployment rate rose much faster than could be rationalized by the fall in the job openings rate. Over the past year, the relationship has completely shattered. The job openings rate has risen by about 20 percent between July 2009 and June 2010. Under this scenario, we would expect unemployment to fall because people find it easier to get jobs. However, the unemployment rate actually went up slightly over this period.”

Here Kocherlakota is implicity invoking the Beveridge Curve which seems to have shifted out in this recession. (He references work by Robert Shimer to support his case.) However this point is relatively easy to refute if you bother to refer to economic history. As Murat Tamni and Robert Lindner pointed out ealier this month the Beveridge Curve always seems to shift out after recessions:

“During and after recessions in the postwar period, the Beveridge curve has generally followed a pattern of shifting to the right during a recovery. One potential reason for this could be that even though some unemployed workers start filling the available job openings, workers who had left the labor force might get encouraged by the recovery and start looking for a job, thereby keeping the unemployment high.”

http://www.clevelandfed.org/research/trends/2010/0810/02labmar.cfm

P.S. Please note the last graph.

27. August 2010 at 09:16

Whoops! I meant to write “Murat Tasci and John Lindner.”

27. August 2010 at 09:22

Scott, all three of these are just as much a part of the malinvestment / too much debt / over consumption false boom as housing.

You are not making your point. You are undermining it.

“2. The sharp loss of jobs that did begin in August 2008 was associated with three areas mostly unrelated to sub-prime housing; manufacturing, commercial construction, and services. All three of these turned down sharply precisely when NGDP started falling, i.e. when money got ultra-tight.”

27. August 2010 at 09:33

huem explains how changes in the money supply stream distort the structure of production and employment.

That’s the part of Hume you seem never to have learned, and Bernanke needs to read.

Scott wrote,

” Fed presidents would be better off spending more time reading Hume.”

27. August 2010 at 09:41

Oh, and catching up on some econblog reading, I came across this charming entry by Brad Delong:

“What do we have in America today?

Well, over the past three years…

-employment in logging and mining has risen by 11 thousand

-employment in construction has fallen by 2.1 million

-employment in manufacturing has shrunk by 2.4 million

-employment in wholesale trade has fallen by 437 thousand

-employment in retail trade has fallen by 912 thousand

-employment in transportation and warehousing is down by 333 thousand

-employment in publishing, except internet is down by 147 thousand

-employment in motion picture and sound recording is down by 34 thousand

-employment in broadcasting, except internet is down by 41 thousand

-employment in telecommunications is down by 54 thousand

-employment in financial activities is down by 921 thousand

-employment in professional and business services is down by 1.3 million

-employment in educational services is up by 197 thousand

-employment in health care is up by 789 thousand

-employment in leisure and hospitality is down by 467 thousand

-employment in other serivces is down by 32 thousand

-employment by the federal government is down by 330 thousand

-employment by state and local governments is down by 127 thousand.

All this in the decline from 137.83 million people employed in July 2007 to 129.95 million people employed in July 2010–a 7.88 million decline in employment during a period in which the adult population has grown by 6 million.

I see employment growth in (a) internet, (b) health care, and (c) logging and mining. I see employment declines everywhere else.

That does not look like a story of “mismatch” unemployment–in which demand shifts in a direction that the existing labor force cannot cope with, and the result is structural unemployment in declining sectors and occupations and boom times and rising wages and prices in those sectors and occupations to which demand has shifted. That does not look like that at all.”

http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2010/08/identifying-cyclical-vs-structural-unemployment-a-guide-for-slate-writers.html

If the structural hypothesis is truly correct we have apparently succeeded in malinvesting in virtually everything under the sun. (Thank God for logging, mining and the internet.)

27. August 2010 at 10:03

The “structural” case has several non-trivial arguments that are worth pondering.

1. Demographic Anomaly:

Labor turnover is much less than expected because, coincidental with the timing of this recession, a large bulk of the population is concentrated in the very-near-retirement years, many of which were planning to retire based on the wealth accumulated in their houses and investment portfolio. This ‘wealth’ disappeared, and these individuals have changed their plans to continue working several more years (in organizations that find it difficult to let their senior employees go involuntarily), and which has eliminated the typical “headroom” available in many organization – universities included.

These senior employees are often the highest-paid (whether or not they are proportionally more productive – I have my doubts), and the cash-flow you pay to a 65-year-old can hire at least two 22-year-olds, which causes a disproportionate impact on the hiring of new graduates. This will, of course, get worked out eventually, but not necessarily soon. Yes, near-retirement employees can “hoard” employable slots that they were formerly ready to relinquish. It’s hard to quantify the effect of this phenomenon, but it’s greater than zero and more “structural” than “cyclical”.

2. Labor mobility is constrained as never before: First, there is the trouble people are having with selling their homes quickly in order to move to new employment – especially those that are underwater and need permission for short sales, the stealth stimulus of 1-to-2 years of free rent if one is going through the foreclosure process (and the incentive *not* to move, even for the unemployed, during the free-rent period), and not to mention the price-discovery lag as with my favorite home.

Second, as Matt Yglesias has been mentioning lately, licensure effects are at an all time high in terms of barriers to entry and geographic limitation. Try moving across a state-line and practicing law in a different state without reciprocity. Even credentialed, accredited, and experienced civil servants can be essentially ineligible to obtain identical credentials in another state without essentially “starting over”, which can require repeating several years of supervised drudgery. (Social Work is a case in point). Most Economists know licensing is a problem, but I don’t think they understand how big it is. Again, this is “structural” and is not constant – it seems to have become with time – and it’s to be expected that it would have its worst effects this recession.

3. Mortgage Equity Withdrawal: That this hardly ever gets a mention by anyone eludes my understanding. The percent of all disposable personal income (and by reasonable extension, the consumption component of Aggregate-Demand) that came from borrowing against collateral swung from +9% to -4%. when the historical norm looks to be between 0 and 2% That’s just huge. I’m still waiting to hear why the inevitable bursting of this consumption-boosting “bubble” alone is insufficient to explain a large portion of our AD-decline and economic situation.

27. August 2010 at 10:29

Mark,

DeKrugman is wrong on structural unemployment.

The issue we face is public employees making too much money:

http://biggovernment.com/mwarstler/2010/08/18/unemployed-blame-public-employees/

Around $400B, give or take, annually.

For this money we could have Full Employment (4%) in every decile.

For this money we could hire all 15M unemployed and pay them $24K a year to give each other massages.

There is enough GDP to have full employment, we have a structural sticky wage problem is ONLY ONE SECTOR of our economy.

Again, as in all things it is not a money illusion it is a distribution problem, the wrong people are currently holding too much against equilibrium.

It is IMMORAL to discuss unemployment as a crisis in a free market economy, where the public sector representing 20%+ of the workforce, is immune to the brutal positive effects of productivity gains – unless we first eat all the low hanging fruit.

We may have a professional elite class, we may have an upper middle class – but those people SHALL NOT BE Public Employees – unless they fund / justify those salaries with Productivity Gains.

27. August 2010 at 10:33

At risk of encouraging Warstler:

This is what “not even wrong” looks like.

Yes, yes we can. Unless you are contending that non-specialized labor has zero marginal product.

27. August 2010 at 10:34

And this is mindboggling, too:

Do you know what structural unemployment is? And do you know what the deadweight losses involved are? The sheer magnitudes involved just don’t work here, man.

27. August 2010 at 10:41

Morgan

What the hell does gov employment have to do with loss of employment in so many private industry sectors? You need to try to understand Monetary Economics first. All you seem to be doing is exhortation to your cause.

27. August 2010 at 11:09

Response to Mark above.

One thing everyone seems to be blind to is that U.S. structural production and employment and debt and money and over consumption problems are not problems in a closed economy, they are problems embedded in the structure of the world economy.

This is the damage vulgar Fisher and Keynes thinking does to the mind — it makes it impossible to think of the U.S. economy as anything but a closed economy.

27. August 2010 at 11:12

Morgan — awesome.

A needed reality check.

27. August 2010 at 11:20

Marcus, I see he thinks money is easy. I wonder on what basis.

Morgan, I’m glad Adam Smith agrees with me on IOR.

Mark, Yes, I saw that Krugman post as well. Of course that’s only one of 5 problems I identified.

Congratulations on the PhD! Let me know how the course goes. I could also use some good ideas.

BTW, Declan asked for some readings in level targeting, NGDP target, etc. I couldn’t think of any. Do you know any?

Benjamin, I have a new post on that.

Morgan, I wasn’t impressed by that column.

Paul, Good point.

Mark, Yes, I’ve seen the Beveridge curve stuff, but it doesn’t surprise me. Every recession is different. It doesn’t affect the case for monetary stimulus.

Greg, You said;

“Scott, all three of these are just as much a part of the malinvestment / too much debt / over consumption false boom as housing.

You are not making your point. You are undermining it.”

Umm, all three are basically the entire economy (when included with housing.) So isn’t this the general glut idea? We have too much of everything? We are all living like millionaires, and all we need is more leisure?

Mark, “Let them become lumberjacks” Or how about this Monty Python routine:

http://www.google.com/search?q=i'm+a+lumberjack+and+i'm+ok&hl=en&rlz=1G1ACAW_ENUS378&prmd=v&source=univ&tbs=vid:1&tbo=u&ei=Mw54TI6ZMcP68Aa8u6SfBg&sa=X&oi=video_result_group&ct=title&resnum=1&ved=0CBkQqwQwAA

Indy, Your first point won’t work because the big surprise is how small the labor force is, how many people aren’t looking for work.

The other two points have some validity, but in no way affect the argument that the Fed should try to push up NGDP. (Of course point three is AD, not structural.)

Morgan, Public employees have made wages a bit more rigid, but it’s not the main problem in the recession.

David, I agree.

27. August 2010 at 11:26

Yes, yes I get it. You want to look at the status quo until 2008 as mildly correct. It wasn’t.

Public employees since 1980 have been earning too much money.

I will say this again, ALL GROWTH comes from productivity gains. Meanwhile, our public sector functions with basically NO PRODUCTIVITY GAINS.

This money added up comes very close to the true size of our National Debt minus interest.

Those taxes we are sending in, those private sector jobs that could be built outsourcing government – that’s whats cost the loss of so many sectors in private employment.

If at this point you are shaking your head, because you don’t think this is how macro is practiced. I get it. If it isn’t practiced this way, then there is not such things as macro.

Said another way: assume there is a single global currency, or market choice of private currencies usable globally, with no political union with the ability to print money – is there still macro? Does it exist? Does anyone holding money freely chose EVER say “hey, print more!”

In this world, there is certainly still micro, so when we are able to see CLEAR and DISTINCT micro solutions, and recognize that the problem we are facing (sticky wages of public employees) is a PURELY Political Union problem (our problem exists BECAUSE we can print money), it behooves us to ask ourselves if the people PRESCRIBING macro solutions, are being honest about their own agenda.

So in macro, Scott advocates that in order to solve for this little blip in unemployment, we need to tax all savings 4% a year forever.

Talk about SHEER MAGNITUDES, are you insane?

Meanwhile in micro, the UAW acquired GM, and and instantly deeply cut salaries for new hires. Price stickiness in private unions? Not so much.

Look, theres only one way public employees are going to be structurally recast – and this is it. This is the state we are brought too, trying to get the services we want from government, but allowing them to collectively bargain against the private sector.

If you don’t feel it or see it, or want to, its not because it isn’t there. Its there if the Tea Party says its there.

Expectations and all that.

27. August 2010 at 11:32

Scott,

Evidently great minds think alike. Alas your link didn’t work for me. Thus, alow me to add the following.

I didn’t really want to end up an macroeconomist. I wanted to be a lumberjack, leaping from tree to tree as I float down the rivers of British Columbia. The giant redwoods, the large, the fur, the mighty scots pie, the small freshnut chamber, the crash of mighty trees, with my best girlie by my side. We’d sing, sing, sing…..

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_n7y_j_nbBg

27. August 2010 at 11:46

Scott $400B is not, “a bit more rigid,” if you don’t think this is the real number, then we have a REAL debate.

If you will accept that $400B is the real number, then why were you so DESPERATE in your previous post for 10% of $1T in printed money to make out as bank loans?

That is a PITTANCE compared what I’m talking about, mine is ANNUAL savings… new private sector growth and savings.

Look, maybe I can explain it this way – we are just months away from a glorious new political agenda: pro business, anti-public employees. This stuff means something.

It is irresponsible to not wait and see whats what in November. 4% inflation forever on purpose is a desperate act, we should pull that trigger ONLY when we’ve tried it the Tea Party way.

27. August 2010 at 14:12

http://globaleconomicanalysis.blogspot.com/2010/08/schwarzenegger-on-public-pensions-and.html

27. August 2010 at 17:44

As a citizen of a developed country which avoided the GFC and the Great Recession, I take it that the “Austrian” analysis is that we Downunder avoided all that malinvestment that America did not. Clever us.

Canada must have as well, since we had about the same decline in employment (2.3% Canada, 2.4% in Australia) and employment levels have now recovered to August 2008 levels. While, on structural unemployment, we avoided all those problems too.

And, from Morgan’s analysis, somehow we avoided overpaying our public servants so much, or somehow it did not matter, or something. And that we Downunder now have the most over-priced housing in the developed world means … Well, I am not sure what it means on Morgan’s analysis.

Alternatively, Canada and Australia’s NGDP did not fall anywhere near as much below trend at the US’s because our monetary authorities performed better. Now, let me think, which covers the three cases better …

Keep up the good work Scott.

27. August 2010 at 23:36

Scott, it’s the time structure / relative price structure of the whole productive economy, yes. (But actually you did not in fact identify the whole productive economy, not even close.)

But this has NOTHING to do with “general glut” economics.

It’s the opposite of that, as Hayek explains in book 4 of his _The Pure Theory of Capital_.

Keynes sold of a repackaged version of the centuries old crank economics of the “general glut” — Hayek was the one who explained why none of that made any economic sense.

Scott writes,

“Umm, all three are basically the entire economy (when included with housing.) So isn’t this the general glut idea? We have too much of everything?”

28. August 2010 at 01:43

What if the combination of the fall in housing prices and increased underemployment has created the expectation that people (a significant portion) have had a permanent decrease in income?

What if the Obama policies, increased taxes and regulation (a different often more extreme tax), are also viewed as a decrease in future permanent income (a net loss for the economy as more resources are misallocated to game the system).

While inflation may make wages less sticky will it be enough to make people feel richer and expand consumption?

While inflation may increase the nominal value of homes (or decrease the debt burden for some) again, will that be enough to increase output?

Perhaps the path Scott recommends is better then many alternative paths offered but can it overcome the fear that political players will seek to capture much of the gain from increased output?

Recently I was looking at the history of Ireland 1920-1940. It is amazing how bad political policies that lead to bad economic policies can create suffering in a population. Acting as if bad economic policies can be erased by inflating the economy seems wishful.

28. August 2010 at 12:14

@Lorenzo from Oz

Over-priced housing isn’t a problem. Values of things do rise and fall. Setting public policy to keep those prices from falling is a problem. Printing money to do so compounds the the nastiness.

Also, I’m not saying that public employees need to make less money, I’m saying there needs to be less public employees. In all things public (even more so than the dog eat dog world of private sector), savings/efficiency/productivity is a top concern. So sure this means that cashiers in public buildings need to be paid minimum wage without benefits, but mostly this is about real productivity gains. I refer tot this as GOV2.0.

In corresponding sectors (information management, customer service, corporate management of all stripes) of our private industries, since 1994, there’s no player who hasn’t pushed past 25% productivity gains – or been driven out of business.

In truth their gains have been MUCH HIGHER.

If you don’t state “yes, the public sector should be subjected to this reality,” than you pretty much aren’t worth talking too.

Now that you agree, we suddenly have $400B per year not being spent on public employees, and another $100B BEING SPENT on private sector technology and service providers.

My 100% correct observation is that IF we had these gains in pocket, we would not be in this situation.

Do you have a real point to make? Or do you wish to keep comparing AUS and CA to the US.

28. August 2010 at 13:49

Do you have a real point to make? Or do you wish to keep comparing AUS and CA to the US.

Comparing different economies over a given time period is what you might call something of a “natural experiment”: it allows you to get a grip on what causal factors matter and what does not.

That public sectors could be more appropriately sized is true, but not a cyclical issue. Especially given that the US, Canada and Australia have public sectors of similar scales relative to GDP and total employment. (In Australia, the level of unfunded superannuation/pension liabilities has been cut right back, but that is just part of much better fiscal policy in general, because we have so much less room to manouevre on that anyway.) So, we can see that optimising the public sector (however desirable otherwise) is irrelevant to the severity and length of the downturn experienced.

That US Federal housing policy has been a sustained disaster is also true but, as Scott keeps pointing out, started falling apart well before the rest of the economy. The 1980s S&L disaster led to neither a general financial crisis nor a massive downturn. (There are some useful comments about different operation of housing credit in this piece on the Australian stock market having the highest returns and the lowest volatility of any stock market in the world over the last 100 years.) But claiming that “overpriced housing stock” is not a problem, except where the government is keeping prices artificially high (i.e. overpriced), seems a bit odd, particularly given that Australian housing prices are what they are due to government-created artificial scarcity in housing land (something I comment upon here).

This blog is first and foremost about the cyclical issues. Confusing the structural with the cyclical (whether passing off the cyclical as structural–see different unemployment experiences–or the structural as cyclical–see my points about public sectors) is a very poor basis for policy.

28. August 2010 at 13:53

Mark, Thanks, and now for something completely different:

Me: The economy is dead, dead I tell you.

Bernanke: No, it’s just resting.

Me: I tell you things look hopeless!

Bernanke: Now your scary talk has stunned it.

(Monty Python fans will understand this nonsense.)

Morgan, You said;

“we are just months away from a glorious new political agenda:”

Is this like the rapture?

Seriously, after the Bush years you expect some sort of capitalist utopia just because the GOP picks up a few seats?

Lorenzo, Thanks for putting things in proper perspective.

Greg, I was reacting to your statement, which seemed to suggest we had produced too much of almost everything.

DanC, You asked;

“What if the combination of the fall in housing prices and increased underemployment has created the expectation that people (a significant portion) have had a permanent decrease in income?”

Economic theory suggests that that would raise employment, as people worked hard to rebuild their wealth.

You asked;

“While inflation may make wages less sticky will it be enough to make people feel richer and expand consumption?”

I don’t want to expand consumption, I want to expand production.

You said;

“Acting as if bad economic policies can be erased by inflating the economy seems wishful.”

I agree, which is why I prefer steady NGDP growth.

28. August 2010 at 16:47

Seriously, after the Bush years you expect some sort of capitalist utopia just because the GOP picks up a few seats?

Scott, do you not remember 1994?

End welfare as we know it, sounds exactly like ending unemployment as we know it. And frankly, I think the lump sum sounds nice, but far more crucial is the forced training system (run by private companies, and offset by taxes) I’ve been describing. The quicker we realize “education” is really “worker training” for most people the better.

The ability to set the tax agenda, and simultaneously take on Public Employees is next.

Is it the rapture? No.

Will businesses suddenly feel like there’s MUCH LESS chance of some government sh*theel coming and poking around their endeavors.

Yep it matters. And I get you are an egghead, but you really should be able to understand

Example: the moment they toss the Individual Requirement, the rest of Obamacare unravels – it is exposed as unaffordable.

But this I will promise you, if the repubs regain one or both houses, things will change. It’ll be nothing like Bush, it’ll be A LOT like Chris Christie.

And there is no better man for this age right now than Chris Christie.

28. August 2010 at 16:56

Lorenzo, there is no cyclical issue that you understand.

There is a normal business cycle, swings in cost of credit based upon the amount of savings there is to borrow. But this cycle has none of the swings we are seeing AS LONG AS we do not pretend for a second that printing money is a moral thing, or an economically intelligent thing.

Scott says he doesn’t want to inflate away bad economic policies, except when he wants to target NGDP to inflate away bad economic policies.

Note: Scott doesn’t ever get down into the weeds of what is moral. I keep saying, to be moral, list ways to target NGDP which puts the new money into the hands of the current savers, and gives no advantage to the ones over-leveraged.

This would show he’s aware of the moral side, and willing to prove he’s only after one thing and one thing only.

So far, no one here has taken that challenge.

29. August 2010 at 04:49

“”What if the combination of the fall in housing prices and increased underemployment has created the expectation that people (a significant portion) have had a permanent decrease in income?”

Economic theory suggests that that would raise employment, as people worked hard to rebuild their wealth.”

With all do respect Scott, another path is a sharp reduction in expenditures. Especially if the politicians are taxing possible gains at increasing rates.

I can agree with you that changes in monetary policy can spur growth but still wonder if the affect will be greatly muted by anti-growth government taxes and regulations.

Perhaps, I don’t know, but what if some members of the Fed share the same view? That QE will not translate into real growth because fiscal policy is anti-growth. In such a world could QE lead to more dollars chasing fewer (or the same) goods?

So Scott could you please explain why you think this is not a possible outcome?

29. August 2010 at 08:26

Morgan, you said;

“The quicker we realize “education” is really “worker training” for most people the better.”

Yes, and I go even further. There’s really only one kind of effective worker training: JOBS

I hope you are right about Chris Christie rather than Bush. We’ll see.

DanC, You said;

“With all do respect Scott, another path is a sharp reduction in expenditures. Especially if the politicians are taxing possible gains at increasing rates.”

That depends on monetary policy, which drives NGDP. (I presume you mean nominal expenditures.) If the Fed keeps NGDP rising, and real expenditures fall, then it doesn’t cost jobs, it causes a trade surplus.

DanC, You said;

“Perhaps, I don’t know, but what if some members of the Fed share the same view? That QE will not translate into real growth because fiscal policy is anti-growth. In such a world could QE lead to more dollars chasing fewer (or the same) goods?

So Scott could you please explain why you think this is not a possible outcome?”

You are mixing up several issues. What is the optimal level of NGDP growth? Does it depend on structural problems such as government intervention? And what happens if you have structural problems?

The optimal level of NGDP growth is along a 5% trend line, that we are now far below that trend line. This does not at all depend on whether there are structural problems. If there are structural problems, you end up with stagflation, which would be better than the alternative in that situation. As you’ve noticed, there is no sign of stagflation right now, so what could possibly be the objection to raising core inflation to at least 2%?

The bad effects that most people assume flow from excess inflation, actually flow from excess NGDP growth.