Investment flows and population growth

I saw an interview of Robert Shiller and Kenneth Rogoff at Davos, where they were asked about the sluggish level of investment in the US. They spoke of a lack of animal spirits, lingering effects of the financial crisis, etc. I wonder if we are underestimating the role of population growth.

For instance, suppose houses lasted forever. In that case a permanent reduction of population growth from 2% to 1%/year would cut housing investment in half. Even in a more realistic model, where a small fraction of houses are demolished each year, housing construction might fall by 20% or 30%.

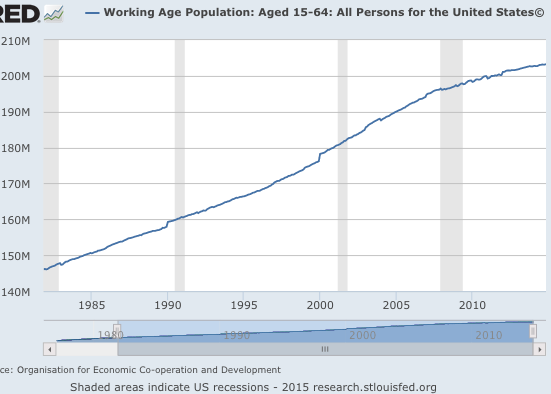

It also seems to me that the working age population might be especially important, as they need workplaces, which are provided via new investment. Here’s a graph of the US population from age 16 through 64:

It looks to me as though working age population growth suddenly slowed down around the onset of the recession. Because the most recent datum is November 2014, I went back seven years to November 2007. The total growth from 2007-14 was 3.63%. For the seven years before that it was 9.61%. For the seven years before that is was 9.15%, and from 1986 to 1993 it was 7.21%.

So in the late 1980s and early 1990s working age population was growing at about 1% per year. Then growth sped up to well over 1% for 14 years. Then when the recession began growth slowed to about 0.5%. That seems significant.

Is it just the recession? We are now seeing unemployment falling sharply, but growth seems to be declining even further, to just 0.31% in the last 12 months, far below the growth rates that America has seen for many generations. And with rising disability rolls, presumably the number of non-disabled working age people is growing even more slowly.

Two theories:

1. Boomer retirements.

2. Less immigration.

I’d guess some of each–does anyone have the data?

Whatever the cause, this seems like it might be able to explain at least some of the sluggish investment and low interest rates. And if it was just the recession, obviously yields on 10 year bonds would not be below 2%. After all, unemployment is down to 5.6% and falling rapidly. The past 10 years have been subpar, but cyclical factors can’t very easily explain low yields for the next 10 years. On the other hand, if working age population growth continues to slow, then we’ll begin to look more like Japan—the country that first entered the low investment/low interest rate environment.

BTW, Check out my post on Keynesian economics and the 2013 austerity, at Econlog.

PS. With the appreciation of the Swiss franc, shouldn’t the Davos meetings be moved to Innsbruck, which uses the now “worthless” euro.

PPS. James in London directed me to an article showing that the SNB is itching to get back in there buying assets to hold down the value of the SF. No surprise to readers of this blog.

Tags:

28. January 2015 at 13:03

I thought this was a good post. Made me think of the fact that regressing (in log levels) nominal personal income on the labor force and wages gives a really good fit.

28. January 2015 at 13:10

There are many factors for this investment deficit. Today there is a pos in Naked Capitalism discussed how Wall Street is destroying Main Street. You are cordially invited to visit this new website: http://www.i-globals.org for a viable, creative, legal and outside-the-matrix alternative to the broken status quo with respect to universal basic income and monetary sovereignty from a private-sector solution. Thanks and best wishes for 2015.

28. January 2015 at 13:43

While this is a very good point, surely our more immediate issue regarding too much capital chasing too few investments is the $5 trillion of mortgages and the millions of new homes that have been AWOL since 2006, compared to what this economy would have otherwise called for.

28. January 2015 at 13:47

“Whatever the cause, this seems like it might be able to explain at least some of the sluggish investment and low interest rates. And if it was just the recession, obviously yields on 10 year bonds would not be below 2%.”

Population has to explain some of it. Banks are desperate to find loan yield. If you look at the Big Bank deposits and their loans you’ll find an excess of deposits relative to loans, so the banks have a lot of cheap deposits that they can’t get qualified borrowers to take. I think this puts pressure on yields. I think it’s basic supply and demand. The banks have excess deposits (supply) and bid down loans with few takers (demand). Now some of this could be a bottleneck for qualified borrowers (something I gleaned from Kevin Erdmann’s site) but at least some of the drop in demand is most likely related to the slower growth in the working population.

If my hypothesis is somewhat true, then what confuses me is what the impact will be if the Fed raises rates. Prime will go up, so loan costs will go up. Why would the Fed want to slow loan creation if long term yields are around 2%? Wouldn’t that just result in even fewer borrowers?

28. January 2015 at 14:03

Brad DeLong is being bad DeLong again;

http://www.neurope.eu/article/what-failed-2008

‘[Barry] Eichengreen traces our tepid response to the crisis to the triumph of monetarist economists, the disciples of Milton Friedman, over their Keynesian and Minskyite peers – at least when it comes to interpretations of the causes and consequences of the Great Depression. When the 2008 financial crisis erupted, policymakers tried to apply Friedman’s proposed solutions to the Great Depression. Unfortunately, this turned out to be the wrong thing to do, as the monetarist interpretation of the Great Depression was, to put it bluntly, wrong in significant respects and radically incomplete.

‘The resulting policies were enough to prevent the post-2008 recession from developing into a full-blown depression; but that partial success turned out to be a Pyrrhic victory, for it allowed politicians to declare that the crisis had been overcome, and that it was time to embrace austerity and focus on structural reform. The result is today’s stagnant economy, marked by anemic growth that threatens to become the new normal. The United States and Europe are on track to have thrown away 10% of their potential wealth, while the failure to strengthen financial-sector regulation has left the world economy exposed to the risk of another major crisis.’

28. January 2015 at 14:18

Here’s a discussion with data from 2009 looking at the role of increasing Baby Boomer retirements as a driver for deflationary forces in the economy, after having contributed to inflationary forces given the age/income life cycle demographics involved.

With respect to immigration, my sense is that it isn’t much of a factor, especially when a very specific change in fiscal policy adopted just before the recession acted to block young Americans from entering into the labor force in a structural change that has greatly amplified the deflationary effects of the exit of retiring Baby Boomers.

28. January 2015 at 15:03

I wonder if Shiller and Krugman can explain to us (each other?) the difference between animal spirits and confidence fairies?

Nice post. I think the onset of a population slowdown requires some changes in the composition of production. Many of the changes are small and should be foreseeable (the working age population projections for 2015 should have been available about 15 years ago – [mildly joking]). I firmly believe that central banks can guide NGDP in this situation.

28. January 2015 at 15:59

On the Swiss: Would not they be better off declaring a tax holiday and having the Swiss National Bank simply print up the lost revenues?

28. January 2015 at 16:32

Let me try to translate DeLong into plain English…

That is, the Friedman policies were fully effective to the extent applied — although they were applied in insufficient degree by central bankers who were institutionally too conservative to take actions beyond those necessary to block a deflationary fall, as market monetarists complained loudly at the time (and Friedman himself had said earlier about Japan).

While monetary policy was visibly effective, it really was ineffective…

… and thus, for instance, during the first two worst years of the recession, enabled Obama and the Democrats to fixate their 60/59-seat Senate and big House majorities on driving Obamacare through congress — in spite of all polls showing the economy at the top of the voters’ priority list and health care reform at the bottom (e.g.: “economy 49%, health care 2%” ) — while leaving multiple seats on the Fed Board of Governors empty. (Imagine if, oh, Truman had left multiple vacancies on the Joint Chiefs of Staff open for years during the Korean war.)

Proving, QED, that it would have been far better policy to try to convince all these obviously congenitally over-conservative political leaders *and* all their legislatures (starting with Obama and the Democrats in the USA, on top of the Republicans) to adopt *massively larger* fiscal stimulus than they actually did (far larger than $800 billion in the USA) … instead of to attempt the relatively impossible task of appointing three new pro-monetary stimulus members to fill the empty seats on the Fed Board of Governors!

All of which also demonstrably proves that “Friedman’s … monetarist interpretation of the Great Depression was, to put it bluntly, wrong” via the logic of, oh, the underpants gnomes.

28. January 2015 at 17:03

On fiscal austerity, it seems like there are three possible definitions:

1. A deficit is fiscal stimulus; a surplus is fiscal austerity.

2. An increase in deficit is fiscal stimulus; a decrease is fiscal austerity. (Reverse for surplus)

3. A reduction in taxes or increase in spending from what was previously done is fiscal stimulus; an increase in taxes or reduction in spending from what was previously done is fiscal austerity. (Static budget scoring)

Which is the definition Keynesians use? I think they use either 2 or 3, but I’m not certain.

For example, I think they consider the 1990 budget deal fiscal austerity, even though the budget deficit increased afterwords – so that leads me to think they mean 3.

28. January 2015 at 17:04

Thanks John.

Kevin, Yes, real estate is depressed after the crisis, but it seems like a long term problem, and presumably real estate will bounce back.

Anthony, Good question. With 1.7% 10 year yields and very low TIPS spreads, it’s hard to see much need for higher fed funds rates.

Patrick, He’s wrong, I’ll do a post.

Ironman, It seems to me the effect is to produce low real interest rates, not deflation.

Bill, Good point.

Ben, The Swiss know how to end deflation, they just don’t want to.

Jim, Very good comment. I’ll do a post.

28. January 2015 at 17:06

Negation, In this case 2 and 3 are similar, as there was no turn in the business cycle during 2010-14.

28. January 2015 at 18:32

There’s an older paper (1978) on the demographic shift of the 1920s that helped lead to the Great Depression.

http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/1057202?sid=21105194534391&uid=3739728&uid=3739256&uid=4&uid=2

I wish it were updated to have more data; I can’t fully believe it without more support of the thesis. But it’s similar to what you are saying.

28. January 2015 at 18:38

The economy is suffering from regulation and inflation. They are cancers.

28. January 2015 at 19:57

Scott, I used “Core minus Shelter” to formulate the Taylor Rule instead of “Core”, and it lines up much better to rates than the regular Taylor Rule does. Shelter inflation has been high because of a supply shortage, except for a brief time around 2005.

The adjusted Taylor Rule also signals a rate decrease in 2006.

http://idiosyncraticwhisk.blogspot.com/2015/01/december-2014-inflation-and-adjusted.html

I’m mulling a theory that the volatility in housing that is related to ultra-low interest rates is causing housing to be counter-cyclical monetary policy. Currency was growing pretty slowly in the 2000’s, but increasing housing prices that resulted from low long term rates were leading to excess credit creation. When real long term rates recovered in 2005-2006, nominal home values naturally leveled off, so that now they were countering momentarily loose policy. But, it is very hard for the yield curve to invert. So, when the Fed pushed short term rates up so high that the yield curve flattened, long term rates couldn’t adjust down far enough for home values to naturally rise to accommodate credit creation again. And, the Fed, having grown accustomed to a tighter policy stance for the previous decade, remained too tight.

I suspect there are error’s there, which you are welcome to point out.

28. January 2015 at 19:58

@everybody- notice Sumner promises Jim he’ll do a post on a convoluted explanation of DeLong’s post–a post on a post on a post–but he refuses to do a post on: (1) how his NGDPLT framework works in terms of mechanics like NGDP futures markets and ‘targeting’ of the same, with ‘pegs’ (whatever that means) and if the Fed is duty bound to keep printing money until a target is reached, (2) why Fischer Black is wrong on Fisher’s quantity theory of money, and (3) why, if Sumner agrees Fed responses are coincident with market forces, and do not precipitate and/or steer market forces, his NGDPLT scheme will work.

In other words, Sumner posts on obscure unimportant stuff but avoids the big questions.

28. January 2015 at 21:37

Huh, so apparently Eichengreen’s new book is about how Friedman was all wrong?

https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/2008-financial-crisis-lessons-by-j–bradford-delong-2015-01

28. January 2015 at 22:38

Ray Lopez continues to compete with major freedom for top crazy person on this blog.

Ray, he’s written abundantly on NGDP futures markets you fool.

29. January 2015 at 00:49

@Edward: not, fool. What paper? The one on this blog in the About/FAQ section is not specific enough. Can you explain it to me? If so, try. For example, after the Fed “pegs” a NGDP target, from the futures market, what happens if in the next day (or hour), due to speculation, the NGDP futures flip in sign? Are you going to reverse policy? If you say that will never happen, that NGDP futures markets are more stable than that, pls say so. That’s just one of many unresolved points.

29. January 2015 at 02:21

“that NGDP futures markets are more stable than that,”

Once upon a lifetime ago, I remember the exchanges calling me regularly to see if I would have interest in supporting new products. They would sometimes even have these little wine and cheese parties for it.

My 3 main criteria:

1- would the product have a natural buyer/seller (volume),

2- does it function in an arbitrage anywhere (volume and hedge-ability) i.e, Heating Oil that continues to trade over the summer, only because it is part of a crack spread with Crude and Gasoline. 3- Most important of all. How volatile? If it has low volatility it would require enormous positions to make any profit, new products have low volume which makes taking a large position extremely difficult. I’m not worrying about putting on a big position, I am worried that without liquidity I will never be able to get out of it once it’s on.

29. January 2015 at 04:13

Ray,

A peg in a financial market is a very simple concept. From the content of your question, it is clear you do not understand it. As a result, you should take some time to study financial markets so you can understand this basic concept. With your super-mega-crazy-enormous IQ, I’m sure this won’t take long.

29. January 2015 at 06:11

Warren, Thanks, but of course I’m not saying that a demographic shift led to the Great Recession.

Kevin, I’m kind of skeptical that housing is closely related to the macroeconomy, until late 2008, when plunging NGDP reduced housing prices sharply. Before that it seemed driven by its own internal factors (moral hazard, myopia, etc., not monetary policy. There just wasn’t enough variation in NGDP growth to explain major moves in the housing market.

Ray, I’ve answered your first question a zillion times in posts. I do not recall Black’s precise view of Fisher’s QTM, but I vaguely recall that Black wanted to use finance theory to explain the value of money. Is that right? Monetary policy is a coincident indicator that causes changes in NGDP.

On your second comment, you obviously have not read my NGDP futures paper. Under my proposal NGDP futures prices do not change when being targeted by the Fed. Read my Mercatus paper.

Saturos, I’ve written a post on that, will be up soon.

derives, You asked:

“would the product have a natural buyer/seller (volume)”

I certainly hope not, it works best if there is no natural market. Read my Mercatus paper on NGDP futures paper if you want more info.

29. January 2015 at 06:22

Isn’t the bad monetary policy of 2008-9 the main reason investment is lagging?

On the labor front, we are definitely seeing reduced labor supply. There are lots and lots of jobs that people who grew up with higher living standards want to avoid. That’s why the WSJ has stories about welders making $140K, IT departments are full of H1Bs, and Mike Rowe is a thing. It could also drive an increased reluctance to invest in projects that require certain skillsets.

29. January 2015 at 10:25

Not strictly in answer to your request for numbers but you may wish to look at the list below. Each site analyses the working population.

Fujitsa, Philidelphia Fed

Atlanta Fed

D Short,

http://www.advisorperspectives.com/dshort/commentaries/Stuctural-Changes-in-Employment.php

29. January 2015 at 10:52

Here’s a longer, annotated view of US population growth, from 1910. Bottom line: The Great Recession looks a lot like the Great Depression. Anyone surprised?

And look at what happens after the Great Depression.

http://www.prienga.com/blog/2014/11/25/us-population-growth

And by the way, initial unemployment claims just blew the doors off today. 265k. Best since 2000. And this, with a good number of layoffs in oil patch.

http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/2015/01/weekly-initial-unemployment-claims_29.html

29. January 2015 at 11:25

TallDave, Initially yes, but now I wonder if it can still explain the low investment combined with low interest rates.

AM, Yes, but what interests me is working age population, not labor force.

Steven, No surprise that people have fewer babies during depressions, but that has no bearing on this post, which looks at changes in working age population. There was no shortage of working age people in the 1930s, AFAIK.

29. January 2015 at 11:27

am, I should have thanked you for the link, it was interesting despite looking at a different issue.

29. January 2015 at 19:35

Edward:

“Ray Lopez continues to compete with major freedom for top crazy person on this blog.”

I have nothing on you if the competition is who is crazier.

You’re cray cray.

What do crazy people believe? Some believe that a big eye in the sky is out there making sure everyone is safe…or in danger. You’re the kind of cray cray that believes everyone should be made safe by a small group of fascist psychos who control a counterfeiting operation.

You’re nuttier than a fruitcake.

30. January 2015 at 04:08

http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2013/article/labor-force-projections-to-2022-the-labor-force-participation-rate-continues-to-fall.htm

Although not strictly what you are looking for it does review some of the issues mentioned in your post.

This link was posted on EV by Bud Meyers.

30. January 2015 at 05:41

Beyond housing, would a slowdown in population growth effect all investment? Cities have less investment in roads, companies don’t need a new factory, and less oil drilling wells are necessary. (Note the population slowdown would effect consumer spending quicker in the lifecycle because most households start cutting consumption at 50ish so the AD slows down first before AS.)

Also the US is only part of the story here, the larger working age population in the developed and BRIC world is telling the exact same story but to a stronger degree. Japan working age population reached is high point a long time ago while Europe is probably in the midst of shrinking workforce. There is even evidence that China has hit working force population high point with Russia & Brazil slowing down growth. (India is still growing.)

The impact of this population slowdown is huge however, I not sure what economic strategies would get developed world people to have more children. At this point, the most functional and productive state, Singapore, also has one of the lowest birth rate in the world.

30. January 2015 at 07:15

In terms of the Great Depression, we forget there was a huge Baby Bust from 1930 – 1935 at the time. However, the Baby Bust effect on the labor market of a baby bust does not happen until 20 – 25 years later so the Great Depression did not have a labor shortage.

However, look at the early 1950 – 1968 US economy. There was a labor shortage due to the 1930s Baby Bust, WW2 deaths (obviously this effected other nations A LOT MORE), and a very defined labor discrimination market. So companies needed workers and increased benefits to increase job stability.

30. January 2015 at 08:44

Thanks AM.

Collin, Lots of good points. I’d just add that Singapore avoids a population problem by having a high rate of immigration. No surprise that lots of talented Asian want to live there!

30. January 2015 at 10:21

Isn’t the biggest contradiction in modern times? The richer we become, the less we can afford to have children.

And immigration is a short term solution for rich nations (and it will also accelerate the global baby bust) but at some point the flow of workers may stop. Living in SoCal, the number of illegal immigrants is way down. (although I think Texas is more of the final destination now.)

30. January 2015 at 20:33

Collin, It’s not a contradiction, it’s a myth. But it’s certainly a widespread myth.

Generally if something cannot logically be true, it’s not true.

We could draw millions of immigrants from just China and India. Every single year for many decades. And of course there are lots more developing countries.

And the distant future is so unpredictable it’s not worth even worrying about.