If you aren’t confused by the lack of mini-recessions, then you don’t understand the issue

It’s often said that if you think you understand quantum mechanics, then you don’t actually understand it. That may not be true of Eliezer Yudkowsky, Scott Aaronson and Robin Hanson, but it’s true of most average people. (Thankfully, I don’t even think I understand it.)

Whenever I discuss the lack of mini-recessions, commenters will offer explanations. One argument is that the highly diversified nature of the US economy leads to shocks in one sector being balanced out with growth in other sectors.

That might be in some way relevant to the issue (indeed I suspect it is.) But it’s certainly not an explanation. After all, we do have medium size recessions and large recessions. So this “explanation” actually explains far too much.

Think of it this way. Everyone should agree that some factor causes recessions in the US, on average once about every 5 years. Let’s call this factor X, or factors X, Y and Z, if you think there are three primary causes. If big X shocks cause big recessions, and medium X shocks cause medium recessions, why don’t small X shocks cause small recessions?

Maybe there are no small X shocks. But why not? Everything we know about both the natural world and the human world suggests that small shocks are almost always more common than medium shocks, which are more common than big shocks. This is obviously true of things like earthquakes, but also true of human shocks like murders, traffic accidents and wars. Single murders are more frequent than mass murders, single and two car accidents are more common than 10 car pile-ups. Small wars are more frequent than world wars.

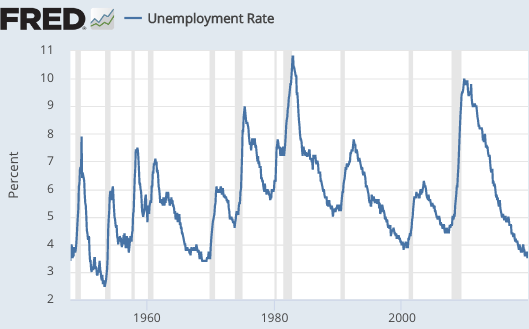

It is true that medium recessions are more frequent than big recessions. So why aren’t small recessions even more frequent? Indeed why don’t we have ANY mini-recessions, defined as unemployment rising by 1.0% to 2.0%, and then falling back.

My hunch is that it has something to do with interest rate targeting, procyclical monetary policy, and policy lags, but I can’t quite figure out exactly how. If the Fed shifts to level targeting and we start having mini-recessions, then that would confirm the role of monetary policy.

PS. The closest we’ve come is the 1959 steel strike, when the unemployment rate rose by 0.8%, and immediately fell back again. Otherwise, a 0.6% rise is the largest increase short of a recession:

PPS. Off topic, you really should be reading Slate Star Codex. Scott Alexander is not an economist, but his posts on economics are often better than 95% of the posts written by economists.

Tags:

6. November 2019 at 12:33

Does the business cycle mean anything in today’s global economy? Sumner: “My hunch is that it (lack of mini recessions) has something to do with interest rate targeting, procyclical monetary policy, and policy lags, but I can’t quite figure out exactly how.” Procyclical monetary policy (augmented by Trump’s procyclical fiscal policy) is what keeps asset prices rising. Rising asset prices doesn’t lead to mini recessions. It leads to financial crisis.

6. November 2019 at 12:51

One reason I always come back to this blog is that Scott not only has better answers than most other analysts of the economy (such as NGDP targeting), but asks questions no one else seems to ask. The questions raise further questions. In this case, is the lack of mini-recessions further evidence of pro-cyclical policy? Intriguing, and seems plausible.

6. November 2019 at 12:59

There certainly are S/M/Large growth slowdowns (just look at the ISM for example)…it’s just that only the M/L slowdowns spill over into the labor market. My hunch is changing hiring plans and/or shrinking the workforce is a last resort. And once that process begins, it is then somewhat self-reinforcing.

6. November 2019 at 13:59

Interesting,

Does the lack of mini-recessions hurt the US? I would feel like they do, but then again I have never looked into the issue deeply. I feel like having sporadic rises in umemployment of a little bit are better than massive losses that are rarer.

I had one thing to ask, remember that story of low population growth from lower immigration in the NYT? Did you ever figure out if that story was true or not? I would feel like a $21.5 trillion dollar country would be rich enough to figure out how much the population grew, even if the estimate was a little rocky.

Also I found this analysis of the OCED estimates for the global economy going toward 2060.

https://www.oecd.org/economy/growth/scenarios-for-the-world-economy-to-2060.htm

It showcases per-capita growth in the US bottoming out at around 1% for the next twenty years, and rising to 1.5% from onward, probably due to technological growth.

It showcases Chinese growth has falling dramatically during the 2020s to 4% growth, and falling to 2% in the decade afterwards. Do you think this is accurate? I think so, especially since East Asian nations often grow fast, then dramatically deaccelerate, often times below western countries, I.E Japan, Taiwan.

Also it shows India converging on China to become the world’s largest economy sometime after 2060, you made this prediction sometime back, so maybe your words from back then are becoming conventional wisdom!

6. November 2019 at 14:08

So the conundrum isn’t so much the presence of mini-recessions elsewhere, but rather the absence of such in the US?

My hunch is that this feature of the US economy has something to do with leverage. Is Australia one of the places which is unlike the US?

6. November 2019 at 14:49

“Off topic, you really should be reading Slate Star Codex. Scott Alexander is not an economist, but his posts on economics are often better than 95% of the posts written by economists.”

May be a more general pattern of Scott Alexander’s essay-posts (but you are speaking to your area of expertise).

6. November 2019 at 15:10

Effem, You said:

“And once that process begins, it is then somewhat self-reinforcing.”

At the firm level or at the national level?

John, I don’t know if it is true, but the government’s own Census Bureau puts out annual population estimates that assume it is not true.

Martingoul, They had mini-recessions in 2002, 2009 and 2014.

Lorenzo. I agree.

6. November 2019 at 16:00

As I am banned on Econlog, I will post a comment here on Scott Sumner’s recent post about the current situation in which the US runs large fiscal deficits and no one talks about it.

—30—

People are also not talking about how the national debt can be purchased back through quantitative easing, except for individuals such as Stanley Fischer.

The track record indicates quantitative easing does not lead to inflation.

There is also the topic that the US economy is growing more robustly than Europe’s, and in Europe they practice fiscal austerity.

Japan, Switzerland, and the United States are all examples of where large amounts of quantitative easing did not lead to inflation.

But!

In contrast, it costs about $2,500 to rent a one-bedroom apartment in Los Angeles for one month, a situation common up and down the West Coast and in a few other major metropolises. This strikes me as a real and major serious issue, which results in real and serious declines in living standards. This is not a theory, this is what you can see in real life.

The two political parties, and the Washington establishment, should be devising plans on how to build not tens of thousands, not hundreds of thousands, but millions of housing units along the West Coast and in a few other major metropolises (preferably through the elimination of property zoning and other incentives for private development, but really by any means necessary).

Your choices for president in 2020 may be Warren and Trump. And it may go downhill from there.

PS: if you think immigration is vital to the US, how do you sell “more immigration” to a guy who pays $2500 for one-bedroom apartment?

6. November 2019 at 19:46

This is a wild guess, but I imagine the weight of expectations set by the Fed keeps things humming along for most of the time. Because we print the world’s reserve currency, we don’t have to worry about smaller shifts. The fed can handle it. So with a small shock, we assume someone is taking care of it, so the small shock corrects itself because we think it will.

But if we don’t expect this self correction, it’s like the Gods come crashing down. So that we can trust our large, diverse, reserve-currency-using economy actually becomes worse when that trust suddenly evaporates.

Anyhow, I really have no idea. But I feel like it’s something like this.

6. November 2019 at 19:52

“If the Fed shifts to level targeting and we start having mini-recessions, then that would confirm the role of monetary policy.” But maybe the effect of a Fed shift to NGDPLT will be: (almost) no recessions at all.

7. November 2019 at 03:43

Maybe it’s because the Fed reacts cautiously and only in discrete quarter point moves, mostly every six weeks. Small Xs can be countered with those moves at that pace but medium and large Xs can’t.

7. November 2019 at 07:24

Scott,

Possible natural experiment. Was sequestration a small X?

Bill,

Your theory, accompanied by the political backlash against larger moves, makes the most sense to me.

7. November 2019 at 09:23

Hi Scott, diversity with underlying positive growth is, as you point out, a good reason for no small recessions. The problem is it’s also a good explanation for there being no recessions at all. I think suggesting shocks that impact the whole economy only come in the medium or large variety is not explaining anything, its just rephrasing the question.

What is needed is a mechanism that makes small shocks unstable, it either reverses them or turns them into large shocks or both. The suggestions you offer are not obviously different in the US vs other places, and im not sure how they make a small shock unstable. They certainly could explain why the restoring force of monetary policy only kicks in later however. Perhaps consumption linked to wealth could be such a reason, eg real economy slow, people see stocks go down, tighten their belts which causes real economy to slow further. This then also needs a mechanism to reverse it so that medium shocks dont turn into large ones, which would be central bank action presumably.

My understanding is US citizens on average have much more wealth tied to the stock market than europeans, I dont know where else this applies to to check if other countries with potentially larger feedback mechanisms have the same dynamics.

7. November 2019 at 10:06

Philo, Yes, that would also suggest that monetary policy played a role.

Bill, It’s still hard to model why there’s a break point between small and medium shocks, no matter what assumptions you make.

BB, I’m not sure, but there must be many small Xs.

7. November 2019 at 10:06

Scott, i was thinking more at the national level. But i could also see why it might be the case at the firm level. If x% of employees aren’t necessary i could see why you might delay that decision..but then as soon as you’ve done some layoffs the rest get “easier.”

7. November 2019 at 14:30

I would argue the FED had a desire to lower inflation from the 70’s and used recessions as a means of lowering trend inflation. Therefore they never reversed policy and eased until well into a recession. Therefore no mini recessions since a mini recession wouldn’t trigger a fed monetary policy response.

I’d argue we just had a mini-recession as the economy espeically industrials slowed. And overall econ data weakened though just a drop from trend growth and not a drop into recession.

7. November 2019 at 16:49

What causes mini-recessions?

My initial guess is that the role of the USD as the world’s reserve currency plays some role in this, as typically aren’t lower interest rates causative of devaluing a currency? If so, that would make the rate cuts of other central banks more stimulative than those of the Fed, as when the US is in or near recession demand for dollar denominated assets tends to rise so much that it makes the USD more valuable than other currencies. So other countries, when they hit an economic shock, have the possibility of devaluing their currency and hence exporting more, importing less, and via that mechanism lowering real wages. On the other hand, when the US has an economic shock, the USD rises in value, increasing imports and lowering exports, raising real wages.

I don’t know if the data supports this theory in anything but the most recent recession, however.

7. November 2019 at 18:15

Fed balance sheet now up $260 billion from September.

https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/bst_recenttrends.htm

If you believe in the efficacy of QE, will this huge jolt of QE propel Trump into White House II?

For the first time in a couple generations, we are seeing real wage increases in the bottom half of the labor pool.

Meanwhile, financiers are crying “there are not enough Treasury bonds in the system to provide liquidity.”

So, should the US Treasury borrow even more money (that is, issue more bonds, that is, the federal government should run larger deficits)?

This will take some serious tin-foil hat thinking….

7. November 2019 at 18:59

@Ben Cole

I think that the 2020 presidential election will be a test of the hypothesis that the economy in the 12 months leading up to the elections determines the outcome of an incumbent US president’s re-election bid, as opposed to approval ratings. It will be an N=1 test, but if Trump loses and the economy is still doing well, then it will one point of data in favor of the economy influencing the election via approval ratings and the approval ratings being the driver of the election results.

Also, if people are so desperate for US treasures, why shouldn’t the government just start issuing debt with negative interest rates? Should solve that problem real fast and improve the fiscal position of the government.

7. November 2019 at 21:59

Scott says:

> My hunch is that it has something to do with interest rate targeting, procyclical monetary policy, and policy lags, but I can’t quite figure out exactly how. If the Fed shifts to level targeting and we start having mini-recessions, then that would confirm the role of monetary policy.

Sean says:

> I’d argue we just had a mini-recession as the economy espeically industrials slowed. And overall econ data weakened though just a drop from trend growth and not a drop into recession.

My question: Scott, do you think that the market anticipating a move to level targeting (or a second best, like average inflation targeting) would already have the effects you foresee?

If memory serves right, your Midas’ Curse was big on the idea that monetary policy has long and variable foreshadowing, not lags. Wasn’t it?

(Btw, you sometimes complain that not a lot of people seem to have bought the book. Perhaps you can wrangle your publisher into giving you permission to post excerpts in your blog? I rather liked the book, and that advertisement might help? In any case, good blog fodder on a slow news day.)

8. November 2019 at 03:50

[…] here and at MoneyIllusion I’ve occasionally done posts on the odd lack of mini-recessions in the US. I define these as […]

8. November 2019 at 09:27

Sean, You said:

“I’d argue we just had a mini-recession as the economy especially industrials slowed.”

No we didn’t. Look at the unemployment rate. It’s not even debatable. I have a very specific definition of “mini-recessions”

Burgos, Check out my new Econlog post, which makes a similar point.

8. November 2019 at 12:00

Hey Scott,

In your previous post on the Sahm rule you said:

“The rule works in the US precisely because we never have any mini-recessions (for some unknown and deeply mysterious reason.) It doesn’t always work in foreign countries because they do have mini-recessions.”

So it is the case that the US does not experience mini-recessions but, for instance, the UK or Switzerland or Australia do? Could you elaborate on that?

8. November 2019 at 22:05

Colin, My newest Econlog post is on mini-recessions in Australia