How’s the economy been doing over the past 6 months?

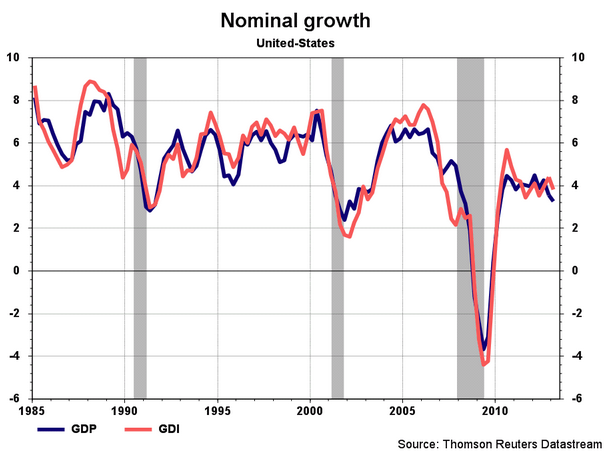

Studies show that GDI is a better measure of GDP than GDP itself. In most cases the gap between the two is relatively small. But over the past 6 months a huge gap has opened up. (It’s useful to look at 6 month figures as the 2013:1 data are hugely distorted by big 2012 year-end bonuses to beat the Obama–GOP tax increases.)

Over the past 6 months NGDP has grown at an annual rate of 2.19%, whereas NGDI (which measures exactly the same thing!) has grown at a rate of 5.06%. I suspect the truth is somewhere in between but closer to the 5.06%. Here’s why:

1. The labor market has been fairly strong over the last 6 months, with job creation accelerating from the middle of last year.

2. All sorts of asset markets (stocks, house prices, bonds, etc) suggest stronger US growth.

3. US consumer confidence has been strengthening.

4. I am not aware of any data confirming an ultra-low 2.19% NGDP growth rate. At that rate there shouldn’t have been any jobs created over the past 6 months.

BTW, if you look at growth by components (which is not a useful exercise) the huge negative over the last 6 months has been military spending. Yay!!

PS. Just to anticipate some comments: I am not suggesting we focus on NGDI instead of NGDP, NGDI is NGDP.

PPS. Yes, I know, the NGDI figures do provide a bit of support for Bernanke. But he still needs to do more.

PPPS. Thomas Raffinot sent me a graph showing that NGDP and NGDI do tend to track each other pretty well over the longer term. (Looks like 4 quarter MA)

Tags:

26. June 2013 at 06:36

“US GDP For First Quarter Revised Down To 1.8% From 2.4% On Weak Consumer Spending” http://www.ibtimes.com/us-gdp-first-quarter-revised-down-18-24-weak-consumer-spending-1323567

26. June 2013 at 06:40

States Are Recovering Lost Jobs at Surprisingly Similar Rates ——> http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2013/06/states-are-recovering-lost-jobs-at-surprisingly-similar-rates.html

26. June 2013 at 07:23

Professor Sumner,

Krugman recently had another post stating that supply doesn’t matter: http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/06/26/aggregate-supply-aggregate-demand-and-coal/

That aside, he says “downward flexibility of wages does nothing helpful when you’re in a liquidity trap.” In Krugman’s view, what then is the problem with low aggregate demand? Downward rigidity in prices?

26. June 2013 at 07:48

Scott

I put up a post with lot´s of stats comparing recoveries, including NGDI:

http://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2013/06/26/comparative-stats-for-economic-recoveries/

26. June 2013 at 08:20

Robert, Yes, this post uses the revised figures.

Aldrey, Interesting.

J, Yes, but we are not in a liquidity “trap.”

Thanks Marcus.

26. June 2013 at 08:21

Why one economist says GDP might be too low —-> http://blogs.marketwatch.com/capitolreport/2013/06/26/why-one-economist-says-gdp-might-be-too-low/

26. June 2013 at 08:33

And this was a ‘tongue-in-cheek’ post on NGDP/NGDPI from some months back:

http://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2013/01/31/ngdp-ngdi-two-sides-of-the-ledger-and-playing-catch-up/

26. June 2013 at 09:16

Again, the best market to look at for your NGDP expectations is the corporate bond spread market, not nominal equity or bonds.

Expectations have backed off a bit in recent weeks after a long run of optimism — but still are nowhere near the 2.5% spread that 6% NGDP would see.

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=jLu

26. June 2013 at 10:01

Very important post which Scott must read (link from Tyler): http://blog.supplysideliberal.com/post/53902444407/sticky-prices-vs-sticky-wages-a-debate-between-miles

26. June 2013 at 10:16

Scott,

what do you think of this, regarding the ‘hot potato’ effect’ and ‘wealth effect’ of monetary policy:

“To be fair, those promoting the ‘hot potato effect’ view do assume that central bank purchases of financial assets would be significant enough to raise prices and thus reduce yields in an economically significant way, which would then ultimately lead to spending on goods and services as agents balance marginal ‘returns’ from consumption with reduced returns to financial wealth. (This is one reason why they have been critical of the Fed’s approach to this point.) There are two important points to make here. First, if such purchases are significant enough to affect the prices of the financial assets being purchased by the central bank, this is an increase in the private sector’s equity through central bank operations, via a capital gain, which is essentially income when realized and thus an act of fiscal policy. However, these transfers to financial institutions with whom the Fed trades are probably far less stimulative than the same-size transfers to households or direct purchases of goods and services might be. Second, promoters of these central bank operations are interested not in these income or fiscal effects – which, again, probably would have small fiscal multipliers at any rate – but rather the effects of the greater quantity of ‘money’ (given their belief that deposits spend themselves) and lower yields for stimulating spending on a greater scale. In other words, if these operations ‘work,’ the stimulus effect would be through either a decision to spend more out of existing income following a portfolio shift to more ‘money’ balances and/or a decision to borrow in order to spend more out of existing income, not any potential (and likely very minor) fiscal effects of the operations. Thus, were QE to work, it would do so almost entirely through additional private sector leverage, not additional income or net financial wealth for the sector.

To summarize and conclude this section, monetary policy stimulus operates via (a) reducing interest rates and thus encouraging agents to borrow or otherwise spend more than their current income – that is to say, increase leverage – and/or (b) raising financial asset prices through QE or related measures so much that it encourages spending via wealth effects. Stimulus method (a) works exclusively through increased private sector leverage, while (b) works almost exclusively through leverage. In the case of (a), the effect is offset at least to some degree by the facts that (i) savers have seen their incomes reduced by both lower overall interest rates and (ii) Treasury pur- chases by the central bank reduce the term structure of the national debt and replace bond interest earnings of the non-government sector with the lower rate paid on reserve balances. In the case of (b), the quantity of operations necessary to generate a macroeconomically large effect on financial asset prices probably threatens to induce asset price bubbles somewhere in the financial system, whether as a result of the cen- tral bank’s own purchases or as a result of speculative actions by financial institutions related to expectations of the effects of the central bank’s actions. Aside from interest rate or supposed portfolio shift effects that necessarily operate to allow additional leverage to ‘work,’ QE-related asset purchases are at best a weak and indirect fiscal action, and at worst can be the impetus for asset price inflation. In short, monetary pol- icy stimulus, because it operates almost entirely through raising the leverage of the non-government sector even in the case of QE, is a stark contrast to fiscal policy that by definition raises the income and net financial wealth of the private sector. This does not by itself suggest monetary policy is inappropriate; it does, however, mean that policymakers and economists should be more detailed in their understanding of the private sector balance sheet effects of different approaches to the macroeco- nomic policy mix and be sure that policy actions are consistent with desired private sector balance sheet outcomes. To date this has not been the case”.

Scott Fullwiler: An endogenous money perspective on the post-crisis monetary policy debate (p.189-90)

http://www.rokeonline.com/roke/post%20crisis%20monetary%20policy%20debate.pdf

26. June 2013 at 10:26

Scott,

why shouldn’t we just use NGDI if its more accurate? Wouldn’t that lead to better policy in general?

I’m curious, do you have info on the shortfall in NGDI starting from the recession?

Also, another question. NGDP in the Bush recovery recovered to trend, but that was one of the weakest recoveries ever. It was nothing compared tot the Clinton boom. Was the shortfall in NGDI from 1999-2000 an explanation

26. June 2013 at 11:44

Scott I agree that GDI is probably a better track than GDP right, now, but considering the gap I wouldn’t cite the studies which assert this. As you mention, the gap is normally a lot smaller than it is today, and those are the conditions under which such beliefs are formed. So in a state where there *is* a big gap, said studies may not be a good anchor.

26. June 2013 at 11:59

Edward,

It was one of the weakest recoveries ever, but also one of the shallowest recessions. Real output barely fell in 2001.

The plucking model implies that the severity of a bust is a good predictor of the strength of the recovery, in real terms, NGDP notwithstanding. So a mild recession will likely be followed by a slow recovery, whereas a boom can be followed by either a severe recession (e.g. the Great Depression) or a mild recession (the early Noughties bust).

26. June 2013 at 12:00

Also, the Clinton boom (really the late 1990s boom) was atypical, driven by exceptional supply-side performance.

26. June 2013 at 12:57

Edward,

The BEA believes that the statistical data that underlies the GDP report is more comprehensive and more relaible. However, i two data sets that are supposed to be measuring the same thing are different, then you have to scratch you head and ask why.

There is a simmilar issue on the employment side. We have the establshment survey and the household survey. The establisment survey is beleived to be a more reliable measure of job creation. If you ever hear a number of net jobs created, that is usually comming from the establishment survey. However, the unemployment rate is derived from the household survey.

26. June 2013 at 15:55

Everyone, Thanks for the links.

Marcus, Someone should do a study seeing if NGDI or NGDP correlates better with employment. Obviously NGDI has correlated better recently, but that might not hold for other periods.

Saturos, I’ll do a post.

James, I’m afraid I disagree with most of that. I don’t believe the financial system plays the key role in the transmission of monetary policy.

Edward, The recovery of NGDP in the early 2000s was far slower than average.

I agree, we should focus on NGDI, or perhaps a weighted average of NGDI and NGDP.

Ashok, I agree.

28. June 2013 at 22:30

More money and spending does not make an economy wealthier in real terms.

“1. The labor market has been fairly strong over the last 6 months, with job creation accelerating from the middle of last year.”

Into what sectors? Are the projects these workers have been hired for sustainable projects relative to each other, given that resources are always and everywhere scarce?

“2. All sorts of asset markets (stocks, house prices, bonds, etc) suggest stronger US growth.”

Never reason from a price change.

“3. US consumer confidence has been strengthening.”

More consumption could mean capital consumption and lower standards of living in the future than what would otherwise have existed. This becomes especially important if investors and consumers have to engage in productive activity using a currency that is not itself subject to market forces, which generates problems for economic calculation and capital structure coordination in a division of labor.

For some reason, macro guys have a difficult time understanding how the market process works (ironic!). We all produce and consume independently. Individuals who produce nails unintentionally coordinate their behavior with individuals who produce wood planks, by way of the competitive price system, not by way of jointly planning all the projects that require nails and wood planks. They each respond to prices (more accurately profits).

Not all NGDPs are created equal. Since Dr. Sumner has recently admitted the existence of Cantillon Effects (through his admission that with inflation, some prices are more sticky than others), then he should understand that NGDP going up or down IS relative spending changes.

Thus, if spending should expand in some sectors relative to other sectors, such that those sectors expand in real terms relative to all other sectors, but this real relative expansions are unsustainable in physical terms (for example too many nails and not enough wood planks), then a nice constant rise in NGDP could very well be associated with an increasingly stressed capital structure that more money and spending cannot solve, because it is the cause of the problem.

“4. I am not aware of any data confirming an ultra-low 2.19% NGDP growth rate. At that rate there shouldn’t have been any jobs created over the past 6 months.”

Did you not write an article on “The German Miracle”? Why this “there shouldn’t have been” language? Does it come from a theory that has been falsified repeatedly, the most recent example being the rise in long term rates after the Fed’s tightening accouncement?

29. June 2013 at 16:24

[…] SCOTT Sumner has a post arguing that the economy over the past six months has improved. He does this by using Gross Domestic Income rather than Gross Domestic Product, and supports his of the former over the later for four reasons: […]

15. July 2013 at 07:29

[…] same since everyone’s cost is someone else’s income. Looking at nominal GDP and GDI, economist Scott Sumner makes the following […]