How strong is the case for helicopter drops?

David Beckworth has a recent podcast with Frances Coppola that discusses the case for a “People’s QE”. Not having read her book, I am not certain about the details of her proposal, but I gather it’s a sort of combined monetary/fiscal stimulus, where the new money is distributed to a cross section of society, not just a few big institutions.

This sort of policy might well “work”, and it might well have been better than what the Fed actually did during the Great Recession. Nonetheless, I remain skeptical of the claim that helicopter drops are superior to stimulus policies that rely exclusively on ordinary monetary policy, such as open market purchases of assets.

Coppola suggests that Japan’s experience provides support for the basic concept:

Beckworth: Frances, do we have any examples of helicopter drops, say pre-2008?

Coppola: Various governments have used forms of what we might call helicopter money, and in the book I do distinguish between different forms of it. But for example, in the 1930s, Japan actually, quite successfully used monetary financing of its government, very successfully, amid dire warnings from American pundits that it was all going to end in hyperinflation, and they were heading for the Weimar wheelbarrows, and they didn’t. They actually came out of the Depression rather more quickly than America did.

And then a bit later this:

I mean Japan, the Japanese Central Bank has been fighting deflation for a quarter of a century. I think we sometimes forget that. So been totally unable to get inflation off the floor.

I have a very different interpretation of the Japanese case. There was a combined monetary/fiscal stimulus in the early 1930s, but the key factor was probably Japan’s (wise) decision to leave the gold standard (in 1931), not the fiscal stimulus. During the Great Depression, countries tended to recover after leaving the gold standard. And Japan was one of the first to leave.

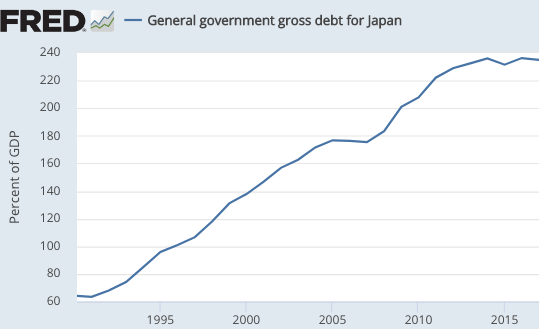

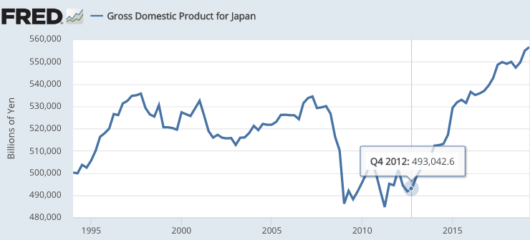

If you want to point to combined monetary/fiscal stimulus, a much better example occurred during the early 2000s, when Japan combined QE with massive budget deficits. Indeed the Japanese fiscal stimulus of 1993-2012 might have been the biggest in world history, for a country not at war. The national debt soared, until Abe introduced fiscal austerity via tax increases:

Ironically, Japanese NGDP began to finally recover at almost the same time that Japan ended its two decade long program of fiscal stimulus.

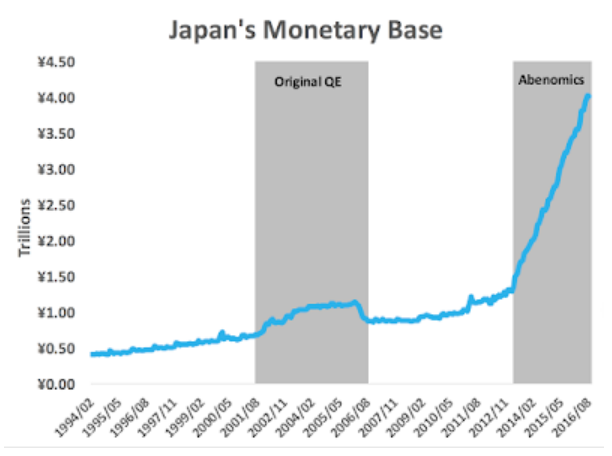

Why did NGDP rise after 2012? Because the Abe administration took office and instituted a policy of monetary stimulus. Most notably, the BOJ began a more aggressive policy of QE (graph from a David Beckworth post):

In fairness, the new BOJ policy has not been completely successful. While Japan is no longer mired in deflation, and both NGDP and employment have been rising, the inflation rate remains far below the 2% target. The new BOJ policy is far from optimal.

Some readers might wonder if my market monetarist outlook is leading to a biased analysis of the Japanese case. OK, consider what Paul Krugman had to say in 2000, when the BOJ raised interest rates:

Consider the contrast: in this country the markets expect the Fed to hold off for a while on interest rate increases even though inflation is running at more than 3 percent. Meanwhile the B.O.J. has just raised interest rates in an economy where consumer prices are actually falling, G.D.P. is lower than it was three years ago, and unemployment is at a postwar high. This says something about what kind of policy Japan can expect from its central bank in the future — and it’s not the sort of thing that would encourage people to go out and spend.

My personal guess is that in the near future, whatever optimism people are now feeling about Japan’s economy will evaporate, and the nation’s malaise will be deeper than ever — thanks in large part to Friday’s action. And while others are more sanguine, both the International Monetary Fund and Japan’s own Ministry of Finance pleaded with the Bank of Japan not to raise rates.

So why did the Bank of Japan do it? Its officials have been talking up the need for higher rates for months, yet have never been able to provide any coherent rationale. Mainly, they claim that ZIRP makes life too easy for corporations, that it lets them put off tough decisions. But there’s no evidence for this — on the contrary, despite the zero interest rate, corporate Japan has lately been experiencing an unprecedented series of high-profile bankruptcies. And anyway, since when is it the central bank’s job to strengthen the private sector’s moral fiber?

And it gets even worse. The BOJ again raised interest rates in 2006. And even worse, they withdrew much of their previous QE (see monetary base graph above.) While the popular view of Japan is roughly what Coppola suggests, i.e., that they tried and failed to stimulate their economy for decades, the truth is that until Abe took office in 2013 they made no serious attempt to push inflation above higher. Whenever inflation seemed about to rise above zero they tightened policy.

In 1998, Krugman had argued that central banks stuck at the zero bound needed to “promise to be irresponsible”. The BOJ did the exact opposite, promising to be ultra “responsible”. I use scare quotes because in this case being “responsible” is not responsible. And of course Krugman’s prediction came true. By not following his advice they pushed Japan much deeper into its zero rate trap, requiring much greater effort when a change of policy did finally occur (in 2013.) If Japan had pushed trend inflation up to 2% in the early 2000s, at a time when it would have been much easier to do so, their job today would be much easier.

In my view, the Japanese case of 1993-2012 shows that combined monetary/fiscal stimulus is no panacea. Rather we need to do monetary stimulus in the right way. Back in 2000, Krugman seemed to agree:

The government’s answer has been to prop up demand with deficit spending; over the past few years Japan has been frantically building bridges to nowhere and roads it doesn’t need.

In the short run this policy works: in the first half of 1999, powered by a burst of public works spending, the Japanese economy grew fairly rapidly. But deficit spending on such a scale cannot go on much longer. Japan’s government is already deeply in debt (about twice as deep, relative to national income, as the U.S. was before our own budget turned around). For the policy to do more than buy a little time, the recovery must become “self-sustaining”: consumers and businesses have to start spending enough to allow the government to return to fiscal responsibility without provoking a new recession.

Carping critics (like me) warned that there was no good reason to think this would happen. Sure enough, it hasn’t; as the big public works projects of early 1999 have wound down, so has the economy.

What can Japan do? . . .

Although the Bank of Japan has already reduced the short-term interest rate to zero, Western economists have pointed out that there are other things it can and should do: buy longer-term bonds, announce a positive target for inflation to encourage businesses to borrow. Indeed, textbook economics tells us that to adhere to conventional monetary rules in the face of a liquidity trap is not prudent; it is irresponsible. (Full disclosure: I personally have been the most visible and vociferous advocate of inflation targeting).

In 2000, Krugman clearly believed that monetary stimulus was more prudent than fiscal stimulus. I think he was right. But he also understood that monetary stimulus would not be effective if it were viewed as temporary. Rather the key is in shifting expectations. Abe’s BOJ has been modestly more effective than the previous version, but much more needs to be done. A good place to start would be “level targeting” of Japanese NGDP along a 3% growth path, with a “whatever it takes” approach to open market operations. Do that and you don’t need fiscal stimulus.

One final point. Some people believe it’s “fairer” to give money to the public as a whole, and not just to big institutions. But ordinary QE doesn’t give money to anyone; it sells money to big institutions at market clearing prices.

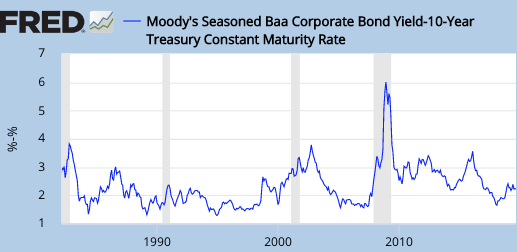

A more sophisticated version of this argument is that QE boosts asset prices. There are two problems with this view. Bond yields often rise with expansionary monetary policy, and this reduces bond prices. That was obviously true in the 1960s and 1970s, but even in the mid-2010s you can argue that when Bernanke did a more expansionary policy than the ECB’s Trichet, the long run effect was to produce stagnation in the Eurozone, and ultimately this produced lower long-term interest rates in Europe. If the ECB had been more aggressive when Bernanke was doing QE, rates in the Eurozone today might actually be higher than they currently are.

The second problem is that when QE boosts the prices of assets such as stocks, it’s largely because QE helps the economy. But a people’s QE would also help the economy, and thus boost stock prices. So “fairness” is not the right way to evaluate alternative monetary strategies.

Certainly the big issue is the need to maintain adequate growth in demand, and on that big issue Frances Coppola and I largely agree. But on the technical question of helicopters drops versus ordinary monetary policy, I still see little need to add fiscal stimulus to the equation, and on efficiency grounds I prefer a clean monetary stimulus.

If there’s a shortage of safe assets, then borrow money to create a sovereign wealth fund. But with trillion dollar budget deficits I doubt there’s a shortage of safe assets.

Tags:

25. October 2019 at 14:17

I don’t think there’s a shorage of safe assets. Everytime I hear there is, I ask, “Why do people want safe assets?” It’s because money’s too tight.

25. October 2019 at 14:29

Scott,

Why do you think risk spreads have remained wide in US?

25. October 2019 at 15:20

If CBs are limited to only purchasing government debt and not using any negative rates, then there is a cap to CBs power even if the CB does everything right.

By “right,” I mean a truly explicit NGDP level target. In *any* condition where the CB undershoots the target, the entire yield curve must be at zero. If the entire yield curve is not zero, then the CB has not done everything it can.

Personally, I do think dollar, Yen and Euro savings demand would have had CBs hit such a condition at different points. While a 1990s and 00s BOJ with NGDPLT may not have needed helicopter money to the extent of Japan’s current debt, I think Japan would have needed *some* helicopter money in the 90s to hit NGDP level targets.

I also think a well-regulated helicopter money system (like Beckworth proposed) is superior to other extraordinary actions (negative rates, negative rate TLTROs). The mere possibility of helicopter money also corrects expectations if markets doubt QE’s direct effects.

25. October 2019 at 15:56

Interesting post, and I tend to favor money-financed fiscal programs, AKA helicopter drops.

What is more interesting is that the world’s largest equity manager, BlackRock, and the world’s largest bond manager, Pimco, and the world’s largest hedge fund manager, Ray Dalio, all now advocate helicopter drops. I am surprised,

In recent generations, Wall Street tended to genuflect to the tight-money totem, at least publicly.

If money-financed fiscal programs are the way to go, we see that Wall Street has moved out in front of central banks and academia in this regard.

We see that former Federal Reserve vice chairman Stanley Fischer is now an advocate of money-financed fiscal programs (Fischer is associated with BlackRock), as was former Federal Reserve board chairman Ben Bernanke when he visited Japan in the early 2000s. Mario Dragi, outgoing ECB chairman, also recently made remarks receptive to money-financed fiscal programs.

I can see why there is such interest now in money financed fiscal programs. How quantitative easing works in a world of globalized capital markets, yet nation-states, is an interesting question to ponder.

Suppose the economy in the US is sluggish. Yet when our central bank conducts QE, it is easing up global capital markets. This is a positive, but reminds me of trying to inflate a balloon by lowering atmospheric air pressure planet-wide.

In contrast, a money-financed payroll tax cut will almost surely be spent entirely inside the United States, and rapidly.

Money financed fiscal programs are direct and effective, and I imagine would be much more convincing to markets and populations of the intentions of the Fed and policymakers.

The markets today believe that central banks are armed with popguns, and there is certainly a lot of op-eds in that regard.

25. October 2019 at 16:15

I also like Beckworth’s approach to helicopter money, but there’s no reason to try it, unless NGDP-level targeting is tried first without helicopter drops and is insufficient.

25. October 2019 at 16:37

Mike Sandifer–

One might argue that the Federal Reserve QE policies were effective after 2008… But on what time scale?

The recovery from the Great Recession was famously the slowest in history.

A recession is no time to be timid. The time to put out a fire is when it’s small, and the time to kill a recession is when it’s in its crib.

25. October 2019 at 16:51

Mike, Have risk spreads remained high?

25. October 2019 at 20:35

Scott,

Yes, your own graph above reveals it. Here are more examples:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=pleS

I’ve been arguing that this, at least in part, reflects tight money. The differences are about what I’d expect, if RGDP was averaging about 1.5% below long-run potential. Other data that I’ve pointed to in the past are consistent with this, but not uniquely so.

25. October 2019 at 20:39

Matthew,

Worrying about interest rates and yield curves is a distraction.

The central banks don’t even need to model interest rates. Eg the Monetary Authority of Singapope uses FX rates in that role.

Equivalently, the fed could just have an NGDP level target, and buy and sell government bonds on the open market, and not even calculate any interest rates, yet alone announce targets for them.

25. October 2019 at 21:04

Benjamin,

The mechanism you describe would be a tragedy of the commons in exactly the other direction. Dollars are one of the cheapest to produce exports, and if foreigners want to exchange them for hard assets like stocks or even fridges, that’s even better. Just do a bigger QE. It’s free.

25. October 2019 at 23:48

Mike,

First, BAA – 10 year spreads bottom out at about 150 bp since 60’s. 2009-16 had a spread around 100-200 bp above the post-1968 minimum. Many periods with NGDP growth have this range of spreads, such as the late-90’s.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=o7Hw

On the second post, it takes an act of Congress to allow the Fed to create helicopter money. Without the law in effect beforehand, the Fed loses almost all expectations effects of possible helicopter money. Maybe Congress would act in a zero-bound event with enough fiscal stimulus (through Fed or by itself), but that’s inferior to the Fed immediately setting fiscal stimulus and having undeniable power to hit NGDP.

26. October 2019 at 00:20

Matthias,

Singapore’s balance sheet is over 90% foreign financial assets ($389bn/$414bn).

It’s frustrating when goalposts get moved. I limited the Fed to buying government assets (Treasuries and Agencies). Of course the Fed could hit NGDP if the Fed started buying junk bonds, foreign currencies or Chinese debt directly. But that’s not legal for the Fed, nor should it be legal.

Swiss or Singapore’s central bank buying foreign assets probably makes sense. You would have to have an extreme amount of helicopter money to meet demand for Swiss Francs.

For the US, a simple counterfactual is if we maintained the same debt/GDP today as we did in 2008. $8 trillion less in Treasuries would be outstanding. Simply reducing 10-year yields by 1.8%, to 0%, would not turn enough savings into consumption of US goods. There would not be $8 trillion more positive-NPV private investments. The exports/FX channel seems to have more elasticity, but the foreign central banks will offset these effects to meet NGDP targets in their own economies.

The other alternatives to Bernanke’s monetary tax cut also feel inferior, in a real GDP sense and a distributional sense. Negative interest rates have been kind of haphazard in Europe. The ECB stopped penalizing a lot of reserves and instead has negative rates at their discount window. Banks can borrow from discount window at, say, -1% against collateral. Since banks compete, this pushes down loans to, say, -0.9%. The net effect is a 0.9% helicopter money credit to the borrower. For lack of other options at ECB, I guess this is okay but it’s utterly bizarre. Only those with collateral and then only those who borrow receive the helicopter money.

26. October 2019 at 00:23

If there’d never been any fiscal stimulus, which seems to be Scott’s preference, there’d be no base money and no govt debt. Apart from the fact that banks would nothing with which to settle up with each other, how would Scott’s preferred option, monetary policy, work in those circumstances? I mean you can’t do QE if there’s no govt debt to buy!!!

Of course there’s the possibility of having the central bank buy assets normally held by the private sector, e.g. stock exchange quoted shares. But assuming the latter assets are best left in private hands, then that policy is pretty clearly not optimal. And one reason for thinking those assets OUGHT to remain in private hands is that it is not the job of central banks to take commercial risks.

26. October 2019 at 01:43

Matthew, yes, I know that Singapore’ MAS doesn’t buy Singapore government bonds. Please abstract from that. But they could eg target the foreign exchange rate, and still buy only government bonds to get SGD into circulation. And not care about interest rates at all.

They couldn’t even run out of government bonds to buy, because they would just appreciate in price.

26. October 2019 at 02:35

Matthew Waters and Scott,

You make a fair point, but you actually strengthened my case. Add RGDP growth to your graph.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=plh9

That brief dip in the risk spread is very much correlated with a spike in RGDP. It’s suggestive,though obviously not definitively so, that the “normal” rate of RGDP growth is close to 3.5%.

26. October 2019 at 06:02

Matthais,

To be clear, I was not saying the Fed needed to do direct targeting of interest rates. My point was the direct power of buying long-term debt would end once those long-term rates hit zero. Should the Fed reach the end of its normal powers, it would look like the Fed pinning the entire yield curve to 0%.

26. October 2019 at 06:04

On a final note, the Fed has statutory power to deal in gold. So if hitting NGDP target is only variable, the Fed could start buying gold at $100,000 an ounce.

26. October 2019 at 06:32

One point on the “unfairness” of QE. The argument is that it unfairly enriches bond holders by lower bond yields and increasing bond prices but if a government was running a primary fiscal surplus and started to buy back bonds presumably this would also lower bond yields? Would that also be unfair? What about a Government that say introduced a rule stabilising fiscal deficit which would probably also lower bond yields? Is any lowering of bond prices unfair?

26. October 2019 at 06:51

Matthias G—

Okay, let us assume the Federal Reserve digitizes 50 billion dollars and buys a lot of hotels in France. The sellers of the hotels in France might consume the proceeds or they might invest in hotels in Australia.

Actually, I find this example confusing.

Okay, let us say that the Federal Reserve digitizes $50 billion and buys $50 billion in US Treasuries and extinguishes the debt. Well, I suppose that deleverages the US taxpayer. I find this example confusing also.

So, the real question is, why is Stanley Fischer now a proponent of money-financed fiscal programs? He has been a central banker, highly-regarded, on two different continents.

26. October 2019 at 09:41

Krugman in 2000: “My personal guess is that in the near future, whatever optimism people are now feeling about Japan’s economy will evaporate, and the nation’s malaise will be deeper than ever — thanks in large part to Friday’s action.”

Krugman was wrong: Japan had five years of strong per capita growth from 2003 to late 2007, the same as the US and the UK.Japan’s per capita growth rate has been about the same as the UK and a little under the US per capita growth from 2001 to 2018.

US 1.3%

UK 1.1%

Japan 1.0%

26. October 2019 at 10:22

A monetized transfer like this seems excessively complicated and to be inching down the slippery slope. Don’t want to get politicians thinking such a thing could be an option.

We know for a fact that standard monetary operations can steer a nominal variable closely around a target, so keep it simple and focus on pushing for 5 year NGDP plans. The core problem is getting the CB to pick and commit to a target. They could drop helicopter money all day and it won’t matter if they offset the stimulus with Forward Guidance or some operation. Think of Sumner’s thought experiment of the central bank offsetting a currency counterfeiter, from some years back.

26. October 2019 at 11:50

We should expect long-term yields rise is a consequence of an easing of monetary policy. If the intermediate and long-term rates fails to move when the central bank announces an easing, that would indicate that the market was expecting something more substantial. The ECB’s easing in 2010 was clearly underwhelming.

26. October 2019 at 13:24

Mike, I guess I don’t quite see that, although perhaps the premium is a bit higher than expected.

Ralph, You said:

“I mean you can’t do QE if there’s no govt debt to buy!!!”

Really? Didn’t the 2009-14 program buy lots of MBSs?

Todd, Yes, in real terms he was wrong. But certainly he was right that Japan would continue to have a deflation problem. He underestimated the flexibility of Japanese wages.

26. October 2019 at 14:14

Scott,

Krugaman didn’t say he thought there would be a deflation problem. He wrote something much more extreme: “the nation’s malaise will be deeper than ever.”

Deflation is not “malaise.” And if deflation has been such a problem, then how could Japan grow as fast as the UK and almost as fast as the US, which had low inflation, the past 17 years?

26. October 2019 at 15:17

I think Ralph implied that there would also be no Agency MBS. The Fed cannot legally purchase non-Agency MBS.

Even buying Agency MBS seems contrary to intent of Section 14. Fannie and Freddie may be “Agency of the United States” in a broad reading, but not like Section 14’s writers had in mind.

26. October 2019 at 15:23

“And if deflation has been such a problem, then how could Japan grow as fast as the UK and almost as fast as the US, which had low inflation, the past 17 years?”

Japanese real wages have been stagnant. Japan’s RGDP looks good due to the GDP deflator.

26. October 2019 at 18:35

For those who posit that QE is enough and does not need to be supplemented by helicopter drops, I do wonder about the recent history of Switzerland.

A couple years back Switzerland wanted to prevent the Swiss franc from appreciating further, as domestic Industries and tourism were being hurt.

Okay, so the Swiss National Bank embarked on a mission to prevent the Swiss franc from appreciating. They ended up buying about $100,000 of foreign bonds, that is non-Swiss sovereign bonds, for every Swiss resident. And in fact the Swiss franc stopped depreciating.

The Swiss still have deflation. Switzerland’s real GDP growth rate decelerated a little bit and is now around 1%.

If the US Federal Reserve were to mimic the Swiss National Bank’s quantitative easing program, it would have to buy about $33 trillion dollars of foreign bonds.

So is QE effective? Then there is the example of Japan. Man, you tell me.

26. October 2019 at 18:56

Scott,

If you look at the average spreads since the Great Recession ended, they’ve been a good bit higher than historical averages, though they started to fall early in 2016, reversing after the trade wars began in early 2018. There’s a pretty large negative covariance between these spreads and GDP growth.

If we assume causation moves from GDP growth to credit spreads, tight money is a plausible possible explanation, but doesn’t seem to be the only one. There could be real factors at work.

27. October 2019 at 09:12

Todd, That’s a fair point, but I think it’s useful to discriminate between different types of predictions. What will happen to NGDP and what will happen to RGDP. One can be right about one and wrong about the other.

Matthew. It’s still a point of trivial importance. Obviously, if there were no Treasuries then Congress would authorize the Fed to buy other assets.

Ben, Your comment on Switzerland is completely misleading. Try reading one of my many posts on the issue. If you want to comment on what I say about Switzerland then feel free to do so. But if you ignore all the posts I’m not going to respond.

27. October 2019 at 09:23

Scott– okay, I will try to find your posts on Switzerland and read them.

27. October 2019 at 09:45

Scott, Re your point about MBSs, I covered that in the original comment of mine above to which you responded. To repeat, if there is no govt debt, then clearly QE is still possible if the Fed buys assets normally held by the private secetor, and presumably BEST HELD by the private sector (e.g. MBSs), but that strategy is by definition not optimal.

Plus what exactly is the big problem with the state (i.e. govt and central bank) creating new money and spending it into the economy so as to deal with a recession?

27. October 2019 at 10:25

Re: Buying private assets. Helicopter money is a question of distributional and RGDP outcomes versus other avenues.

Also, the US exceeds debt levels necessary to hit NGDPLT despite zero lower bound. If Japan had an NGDPLT regime in past decades, they would have also exceeded it. The BOJ is weighed down today by how much market expects deflation to continue.

It is just too politically explosive to buy private assets. If anything, I would eliminate Section 13(3) entirely.

Small CBs with heavy external demand, such as Switzerland, are a special case. The amount of helicopter money necessary would be too scary. They should still only buy FX and other government’s debt though. They shouldn’t act as a SWF.

27. October 2019 at 12:27

“Todd, That’s a fair point, but I think it’s useful to discriminate between different types of predictions. What will happen to NGDP and what will happen to RGDP. One can be right about one and wrong about the other.”

I just went with what Krugman wrote: “the nation’s malaise will be deeper than ever.” That didn’t happen.

27. October 2019 at 14:10

Everyone, As a practical matter there is no need to buy anything but Treasuries if we have a sensible monetary policy (say 4% NGDP growth, level targeting.)

28. October 2019 at 10:12

Ralph –

“if there is no govt debt, then clearly QE is still possible if the Fed buys assets normally held by the private secetor, and presumably BEST HELD by the private sector (e.g. MBSs), but that strategy is by definition not optimal. ”

My understanding is those MBSs were already backed by the Treasury, so there was no default risk associated with the Fed holding them. There may be term risk, but no more so than buying Treasuries of similar duration.

So I would question whether they are best held by the private sector. If it were up to me, the government would never back a loan – it would either make the loan directly (and keep all the profit and assume all risk) or stay totally out of it (and let the private investor keep all profit and assume all risk).

The advantage to the Fed limiting itself to government debt and government backed securities is that those decisions have already been made, i.e., the liability is already there.

28. October 2019 at 20:32

Scott Sumner–

Okay, if you are still reading, I read the four Switzerland posts indicated here:

https://www.themoneyillusion.com/category/switzerland/

Well, obviously, monetary policy, QE and fiscal policy and exchange rates are huge topics with a lot of moving parts, and I am just an econo-gadfly.

Perhaps you should do a post specifically on the Swiss National Bank, and its balance sheet in relation to Switzerland’s GDP and population, and the results for Swiss GDP and inflation.

The SNB now has a balance sheet larger than Switzerland’s GDP. The balance grew as Switzerland tried to regulate the exchange rate of the Swiss franc by buying foreign sovereigns.

https://tradingeconomics.com/switzerland/gdp

https://www.snb.ch/en/iabout/snb/annacc/id/snb_annac_balance

The SNB has a balance sheet of about $95,000 per Swiss resident.

(BTW, the SNB is publicly held and becoming very valuable! I did not know that!).

If the Federal Reserve were to match the SNB balance sheet, it would have a balance sheet of about $20 trillion (GDP equal) or $31 trillion (population equal).

The Swiss economy has chugged along in recent years, in the slo-lo, or slow growth and low inflation.

There is always the counterfactural argument, that is, “Without the huge SNB QE the Swiss economy would have had recession and deflation.”

Still, the SNB executed heroic amounts of QE and the results seem wan.

There is also the fascinating idea of what a lone central bank can do in globalized capital markets. Now, the SNB is small, so it can “get away” with a lot.

Still, it sure looks like the Federal Reserve could effectively monetize US national debt without much inflationary consequence. That is, globalized capital markets are so large that the Fed can exchange digitized cash for Treasuries, without causing global inflation, but with monetizing US debt.

The dollar exchange rate? Maybe some action there, but global capital flows are huge anyway.

Interesting topic.

BTW, the Swiss franc is now equal to one US dollar, almost exactly.

29. October 2019 at 08:06

Ben, You missed the point. The balance sheet grew faster when they were not trying to peg the exchange rate

30. October 2019 at 20:30

Well, okay. Still, the SNB did a large amount of QE…but nothing really seemed to happen.

I agree that forward guidance is useful.