My vision of macro

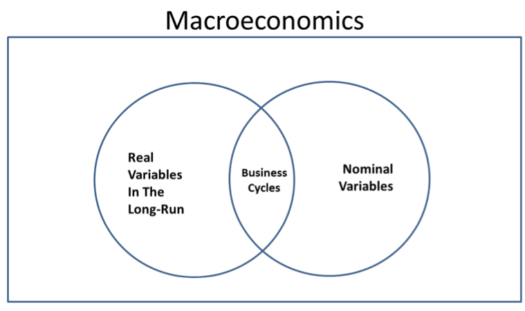

The following Venn diagram helps to explain how I visualize macro:

There are three basic fields within macro:

There are three basic fields within macro:

1. Equilibrium nominal

2. Equilibrium real

3. Disequilibrium sticky wage/price (interaction)

I’ll take these one at a time.

1. Within equilibrium nominal there are important concepts:

A. The quantity theory of money

B. The Fisher effect

C. Purchasing power parity

The first suggests that a change in M will cause a proportionate change in P. The second suggests that a change in inflation will cause an equal change in nominal interest rates. The third suggests that a change in the inflation differential between two countries will cause an equal change in the rate of appreciation of the nominal exchange rate.

All three concepts implicitly hold something constant; either the real demand for money, the real interest rate, or the real exchange rate. In all three cases the concept is most useful when the money supply and price level are changing very rapidly, especially if those changes persist for long periods of time.

2. Equilibrium real macro can be thought of as looking at economic shocks that do not rely on wage/price stickiness. These include changes in population, technology, capital, preferences, government policies, weather conditions, taxes, etc. These can cause changes in the real demand for money, the real interest rate, the real exchange rate, the unemployment rate, real GDP, and many other real variables.

3. Disequilibrium macro looks at nominal shocks that cause changes in real variables, but only because of wage/price stickiness. Thus because prices are sticky, an increase in the money supply will temporarily cause higher real money demand, a lower real interest rate, and a lower real exchange rate. These changes occur even if there is no fundamental real shock hitting the economy. The effects are temporary, and go away once wages and prices have adjusted.

If wages and prices are sticky then an increase in the money supply will also cause a temporary rise in employment and real output.

And that’s basically all of macro. (This is how I’d try to explain macro to a really bright person, if I were given only 15 minutes.)

I also believe that understanding the implications of this three part schema makes one a better macroeconomist. Talented macroeconomists like Paul Krugman tend to have good instincts as to which real world issues belong in each category. Here’s my own view on a few examples. For simplicity, I’ll denote these three areas: nominal, real, and interaction:

1. Most business cycles in ancient times were real, with some interaction. The 1500 to 1650 inflation was nominal.

2. Recessions such as 1893, 1908, 1921 and 1982 were mostly interaction.

3. The Great Depression was all three.

4. The Great Inflation was mostly nominal, especially in high inflation countries.

5. The 1974 recession was more “real” than usual. Ditto for the WWII output boom.

6. The real approach works best for short run shocks to specific industries such as housing and oil, plus long run growth. The nominal approach works best for high inflation rates and long run inflation. The interaction approach works best for real GDP fluctuations in large diversified economies.

7. If one set of economists say the Japanese yen is too strong, and another set say it’s too weak, they are probably using different frameworks. Those who say its too strong are using a nominal framework, and are likely worried about deflation. A weaker yen would boost inflation. Those who think the yen is too weak are using a real framework. Rather than worry about deflation, they worry that Japan has a current account surplus. These views seem to contradict, but it’s theoretically possible for both to be right. Perhaps the nominal exchange rate for the yen is too strong, and the real exchange rate is too weak. You would then weaken the nominal exchange rate by printing money, and strengthen the real exchange rate by reducing Japanese saving rates. (I don’t favor the latter, just saying that’s the proper implication of the misguided worry about Japanese CA surpluses.)

8. Don’t let your policy preferences drive your analysis. Throughout all of my life, it’s been assumed that monetary shocks drive real output by causing changes in the unemployment rate. Not changes in trend productivity growth or population growth or labor force participation or any number of other variables. Money matters because it affects unemployment. If the unemployment rate is telling you that monetary policy is no longer holding back growth, the proper response is not to double down on your belief that we need easier money and then look for new theories to justify it, but rather to conclude that whatever problems we still have are now “real”, not “interaction.”

A good macroeconomist knows that all three fields of macro are very important, and which models apply to each of the three fields, and which field is most applicable to each real world macro issue.