The interwar gold standard is one of the most complex and interesting case studies in all of macroeconomics. I’ve devoted much of my life to studying this issue. It is difficult to wade through all the complexities without eventually getting off course, focusing on the wrong issues and misinterpreting key facts. I’m pleased to say that Hu McCulloch’s brilliant new essay at Alt-M is one of the very best descriptions of this period that I have ever read. I agree with well over 90% of his judgments, including all of the key points. Here I’ll focus on a few small points where I disagree.

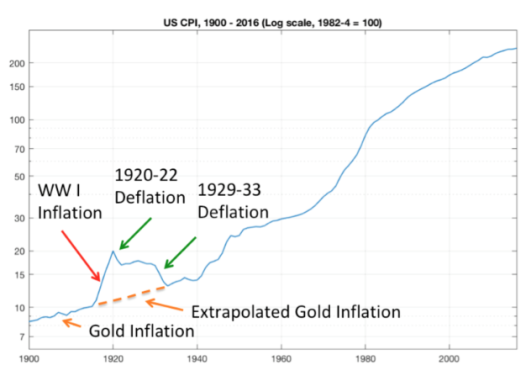

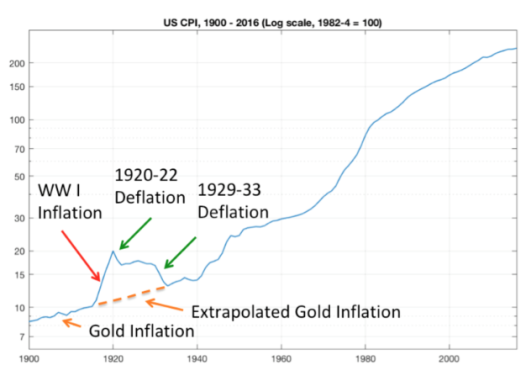

McCulloch argues that the fundamental problem was that European gold demand plunged during WWI, as countries sold off gold and printed money to finance the war. This sharply reduced the value of gold, which meant a higher price level in countries (such as the US) still on the gold standard. Furthermore, it was almost inevitable that once the international gold standard got back on its feet, the value of gold would gradually return to its prewar level. This would mean substantial deflation in countries such as the US and the UK. McCulloch illustrates this idea with a graph:

McCulloch cites Clark Johnson and Doug Irwin, who showed that the adjustment process was made more unstable by the big surge in French gold demand in the late 1920s and early 1930s. He suggests that, (assuming that we stayed with gold) the best feasible outcome was a more gradual deflation over many years, until the global price level got back on track.

McCulloch cites Clark Johnson and Doug Irwin, who showed that the adjustment process was made more unstable by the big surge in French gold demand in the late 1920s and early 1930s. He suggests that, (assuming that we stayed with gold) the best feasible outcome was a more gradual deflation over many years, until the global price level got back on track.

That’s a perfectly valid way of looking at the picture, and indeed is one of the plausible counterfactuals that I discuss in my own book on the Depression. But I do slightly quibble with this statement:

However, given that the U.S. had a fixed exchange rate relative to gold and no control over Europe’s misguided policies, it was stuck with importing the global gold deflation — regardless of its own domestic monetary policies. The debt/deflation problem undoubtedly aggravated the Depression and led to bank failures, which in turn increased the currency/deposit ratio and compounded the situation. However, a substantial portion of the fall in the U.S. nominal money stock was to be expected as a result of the inevitable deflation — and therefore was the product, rather than the primary cause, of the deflation. The anti-competitive policies of the Hoover years and FDR’s New Deal (Rothbard 1963, Ohanian 2009) surely aggravated and prolonged the Depression, but were not the ultimate cause.

He’s right about the banking problems, and also about the New Deal, but I believe he lets the Fed (and Federal government more broadly) off the hook a bit too easily. Here are a few points to keep in mind:

1. The Fed was created partly because the US no longer wanted a “classical gold standard” where the government played no role in preventing crises. The Fed did in fact exercise countercyclical policies during the 1920s. (Whether effectively is a complicated question.)

2. The US had enormous gold reserves in 1929, nearly 40% of the global total.

3. Legal gold reserve ratios could and should be adjusted during a crisis, and indeed Hoover did get Congress to ease the Fed’s gold requirements during early 1932.

4. When the US left the gold standard during 1933, it still had by far the world’s largest gold reserves. I seem to recall that Richard Timberlake once said something to the effect that there’s no shame in losing the gold standard after a valiant effort, what’s shameful is not even trying to stabilize the economy by using “emergency” gold reserves, before completely abandoning the system. When the US left gold in 1933, we still had by far the world’s largest gold reserves.

As an analogy, if in 1912 there was a regulation that all cruise ships should have 20 lifeboats on deck, that does not mean that the lifeboats should remain on deck after hitting an iceberg. Later on, McCulloch indicates that he does understand this problem:

Unfortunately, however, there was often a misguided assumption that central banks (and private banks) should suspend redemptions whenever the legal reserve requirement was not met. This gave them an incentive to hold a substantial amount of excess, or “free,” reserves over and above the legal requirement. Instead, it should have been understood that a bank is obligated to meet its demand liabilities, so long as it has any reserves at all, and that a “reserve requirement” means that it may extend or renew credit to the government and/or the private sector only if it has reserves in excess of the “required” level.

At a minimum, the Fed should have been far more aggressive in doing whatever it took to engineer a gradual deflation after 1926, say 2%/year, rather than allow double-digit deflation after 1929. I believe the Fed had enough resources to do this, even singlehandedly. If you are skeptical of this claim, keep in mind the following facts:

1. Fed policy during the first year of the Depression (October 1929-October 1930) was extremely tight. The gold reserve ratio rose sharply at the same time that France and the UK were also increasing their gold ratios. This was the proximate cause of the first year of the Depression. An expansionary Fed policy would have made the 1930 slump much milder.

2. More importantly, the really big increases in gold demand during the early 1930s came from four sources, three of which were endogenous—caused by the Depression itself. The one exogenous factor was France’s decision to raise its gold ratio. One endogenous cause was the extra gold needed to back base money created during the banking crises that began in October 1930. Without a deep depression, the banking crises might never have occurred, and certainly would have been far milder. Second, many gold bloc central banks accumulated large gold reserves partly in consequence of the Depression itself. Indeed even part of France’s increase in gold hoarding was motivated by the Depression. Thus it rapidly replaced dollar and pound reserves with gold after the UK left the gold standard in September 1931, and people began to fear the US would also eventually devalue. Third, private gold hoarding increased strongly after 1930, once people correctly began to see that various countries were likely to eventually devalue. All three of these causes of sharply higher gold demand were entirely endogenous, and largely explain why things got worse so dramatically after 1929.

Think in terms of the butterfly effect in chaos theory. A modestly more expansionary Fed policy in 1930 could have prevented much of the gold hoarding related to panicky investors fearing devaluation, panicky bank depositors fearing bank failures and panicky governments fearing their paper forex reserves would be devalued. I believe the Fed could have engineered a soft landing, where prices fell at a gradual pace, as European nations gradually rebuilt the international gold standard.

Having said all of that, there’s a good argument against the views I just expressed. This policy regime would have required a high level of wisdom by the central bank. But if central banks were that wise, there would be no point in having the gold standard in the first place. You’d just have fiat money, and then have them target the price level. Furthermore, if the wise policy I sketched began well into the Depression then it would have been increasingly difficult to implement, increasingly likely to lead to a run on the dollar where the US ran out of gold. Thus it would have been easier to implement in 1930 than 1931, and easier to do in 1931 than 1932. So there a lot of truth in McCulloch’s claim that given the institutional set-up of this period, the disruption to the gold standard caused by WWI was the root cause of the big interwar deflation. Certainly Friedman and Schwartz gave too little attention to this problem.

I would also slightly quibble with this:

H. Clark Johnson views the non-monetary demand for gold as a destabilizing factor during the 1920s and points a particularly accusatory finger at India (pp. 46-8). However, the non-monetary demand for gold actually stabilizes prices under a gold standard, since it will reduce the inflation that occurs when monetary demand is reduced (as during the early 1920s), and its reversal will mitigate the deflation that occurs when monetary demand has increased (as at the end of the 1920s and early 1930s).

That’s generally true, and was true in 1930, when the Depression raised the value of gold and reduced private gold demand. Less private gold demand is stabilizing during a depression. But private gold demand began rising sharply after mid-1931, and in several other gold hoarding episodes right through 1933. These bouts of private gold hoarding were caused by fear of devaluation, and this prevented the normal stabilizing properties of the gold standard from having their usual effect. Although I have not studied the mid-1890s, I believe something similar occurred when silver agitation created fears that the US might abandon gold.

My third quibble has to do with the conclusion, where McCulloch makes a few brief comments about the Great Recession. He does not place enough emphasis on the role of tight money at the Fed, which drove NGDP sharply lower during 2008-09.

But these are small points. If you want a quick explanation of what went wrong during the interwar period, read McCulloch’s essay. If this whets your appetite and you want a more complete explanation . . . well you know where to look:

HT: John Hall

HT: John Hall

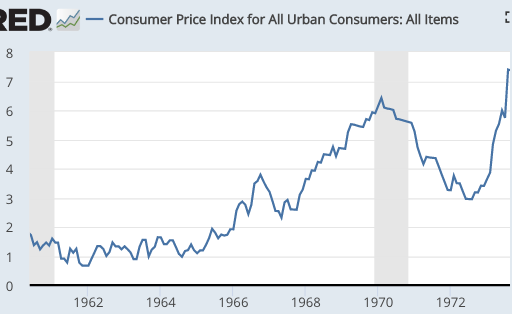

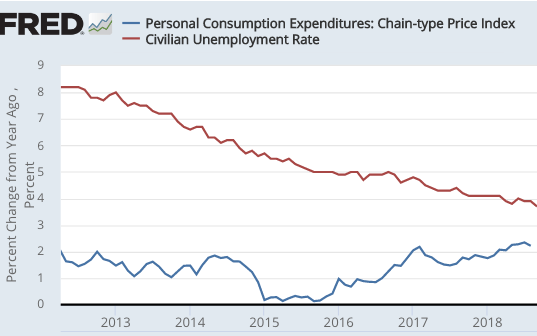

Over the previous 6 years, unemployment has fallen from 8% to 3.7%. Inflation has mostly stayed in the 1% to 2% range, occasionally dipping below 1%, and recently rising above 2%.

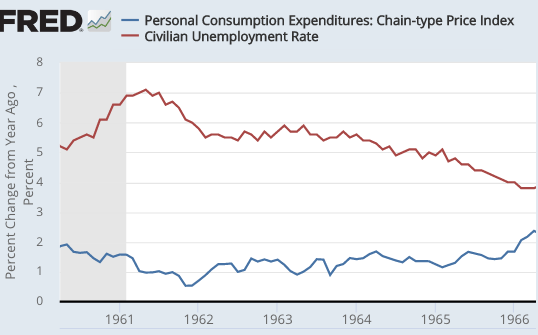

Over the previous 6 years, unemployment has fallen from 8% to 3.7%. Inflation has mostly stayed in the 1% to 2% range, occasionally dipping below 1%, and recently rising above 2%. In this case, unemployment rose to a peak of 7% in 1961, then gradually trended down to 3.8% in mid-1966. Inflation mostly stayed in the 1% to 2% range, occasionally dipping below 1%, and recently rising above 2%.

In this case, unemployment rose to a peak of 7% in 1961, then gradually trended down to 3.8% in mid-1966. Inflation mostly stayed in the 1% to 2% range, occasionally dipping below 1%, and recently rising above 2%.