Irving Fisher and George Warren

I am currently a bit over half way through an excellent book entitled “American Default“, by Sebastian Edwards. The primary focus of the book is the abrogation of the gold clause in debt contracts, which (I believe) is the only time the US federal government actually defaulted on its debt. But the book also provides a fascinating narrative of FDR’s decision to devalue the dollar in 1933-34. I highly recommend this book, which I also discuss in a new Econlog post. Later I’ll do a post on the famous 1935 Court case on the gold clause.

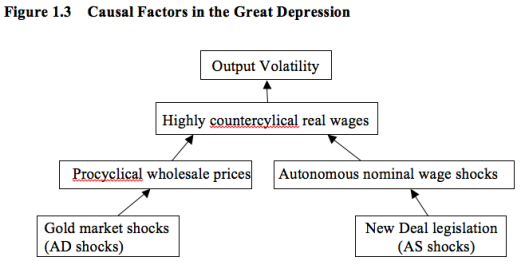

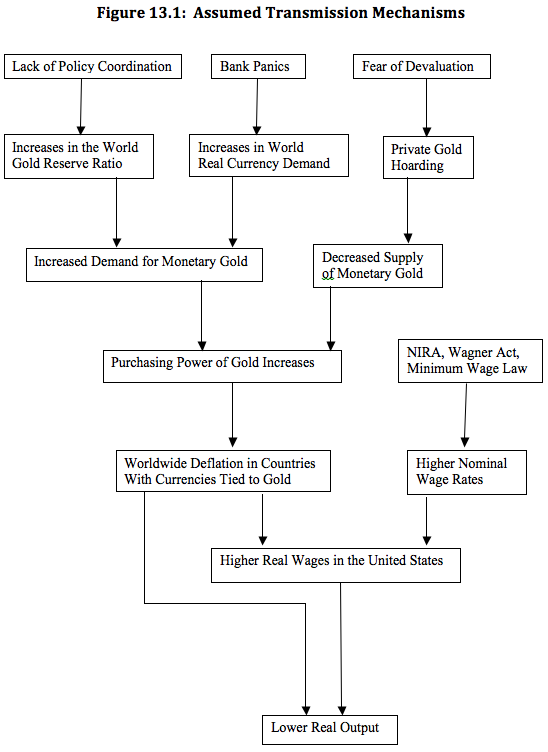

Edwards has an interesting discussion of the difference between Irving Fisher and George Warren. While both favored a monetary regime where gold prices would be adjusted to stabilize the price level, they envisioned somewhat different mechanisms. Warren focused on the gold market, similar to my approach in my Great Depression book. Changes in the supply and demand for gold would influence its value. Raising the dollar price of gold was equivalent to raising the nominal value of the gold stock. Money played little or no role in Warren’s thinking.

Fisher took a more conventional “quantity theoretic” approach, where changes in the gold price would influence the money supply, and ultimately the price level. Edwards seems more sympathetic to Fisher’s approach, which he calls a “general equilibrium perspective”. Fisher emphasized that devaluation would only be effective if the Federal Reserve cooperated by boosting the money supply.

I agree that Warren’s views were a bit too simplistic, and that Fisher was the far more sophisticated economist. Nonetheless, I do think that Warren is underrated by most economists.

To some extent, the dispute reflects the differences between the closed economy perspective championed by Friedman and Schwartz (1963), and the open economy perspective advocated by people like Deirdre McCloskey and Richard Zecher in the 1980s. Is the domestic price level determined by the domestic money supply? Or by the way the global supply and demand for gold shape the global price level, which then influences domestic prices via PPP? In my view, Fisher is somewhere in between these two figures, whereas Warren is close to McCloskey/Zecher. I’m somewhere between Fisher and Warren, but a bit closer to Warren (and McCloskey/Zecher).

There’s a fundamental tension in Fisher’s monetary theory, which combines the quantity of money approach with the price of money approach. Why does Fisher favor adjusting the price of gold to stabilize the price level (a highly controversial move), as opposed to simply adjusting the money supply (a less controversial move)? Presumably because he understands that under a gold standard it might not be possible to stabilize the price level merely through changes in the domestic quantity of money. If prices are determined globally (via PPP), then an expansionary monetary policy will lead to an outflow of gold, and might fail to boost the price level. Thus Fisher’s preference for a “Compensated Dollar Plan” rather than money supply targeting is a tacit admission that Warren’s approach is in some sense more fundamental than Friedman and Schwartz’s approach.

Warren’s approach also links up with certain trends in modern monetary theory, particularly the role of expectations. During the 1933-34 period of currency depreciation, both wholesale prices and industrial production soared much higher, despite almost no change in the monetary base. Even the increase in M1 and M2 was quite modest; nothing that would be expected to lead to the dramatic surge in nominal spending. That’s consistent with Warren’s gold mechanism being more important that Fisher’s quantity of money mechanism. In fairness, the money supply did rise with a lag, but that’s also consistent with the Warren approach, which sees gold policy as the key policy lever and the money supply as being largely endogenous. You might argue that the policy of dollar devaluation eventually forced the Fed to expand the money supply, via the mechanism of PPP.

A modern defender of Warren (like me) would point to models by people like Krugman and Woodford, where it’s the expected future path of policy that determines the current level of aggregate demand. Dollar devaluation was a powerful way of impacting the expected future path of the money supply, even if the current money supply was held constant.

This isn’t to say that Warren’s approach cannot be criticized. The US was such a big country that changes in the money supply had global implications. When viewed from a gold market perspective, you could think of monetary injections (OMPs) as reducing the demand for gold (lowering the gold/currency ratio), which would reduce the value of gold, i.e. raise the price level. A big country doing this can raise the global price level. So Warren was too dismissive of the role of money. Nonetheless, Warren’s approach may well have been more fruitful than a domestically focused quantity theory of money approach.

PS. Because currency and gold were dual “media of account”, it’s not clear to me that the gold approach is less of a general equilibrium approach, at least under a gold standard. When the price of gold is not fixed, then you could argue that currency is the only true medium of account, and hence is more fundamental. During 1933-34, policy was all about shaping expectations of where gold would again be pegged in 1934 (it ended up being devalued from $20.67/oz. to $35/oz.)

PPS. There is a related post (with bonus coverage of Trump!) over at Econlog.