Borat in Hawaii

One of the most interesting things about the long Japanese deflation was the relative stability of the Japanese yen, against the dollar. It’s depreciated about 1% since the end of 1993:

You’d have expected the Japanese yen to have appreciated strongly in recent decades, as the US price level (GDP deflator) has risen from 73 to 100 since early 1994, while the Japanese price level has fallen from 117 to 100. Thus the ratio of US to Japanese prices has risen from 0.91 to 1.62. And that’s not because I cherry-picked the data, as of a month ago the yen was down about 10% against the dollar, since the end of 1993. Thus the deviation from PPP would have been even bigger.

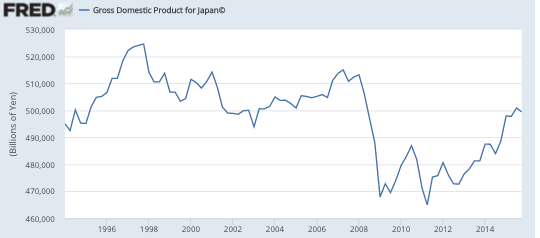

I frequently argue that inflation doesn’t matter, what matters is NGDP growth per capita. Here is the NGDP of Japan since the beginning of 1994:

It’s up about 1%. But Japan’s population is up about 1% or 2%, depending on the source, meaning that NGDP/person is either flat or down 1%.

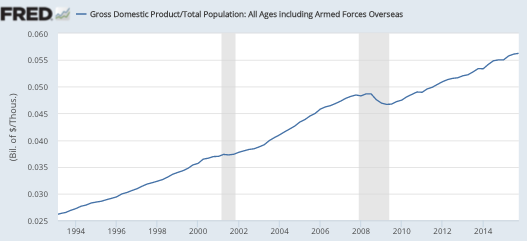

How about in the US? The following graph shows NGDP/person:

So in the US NGDP/person is up about 106.7%, versus at most zero in Japan. You might say that’s comparing apples and oranges, as one is in dollars and the other is in yen. But as we saw the exchange rate is pretty stable since the end of 1993. On the other hand, if PPP does not hold, what difference does that make? RGDP in Japan has been rising, so Japanese living standards are on the way up.

Here’s how I would interpret this data. This is telling us that compared with early 1994, Japanese tourists have become much poorer in a relative sense, every time they visit Hawaii. Relative to American tourists, they have a hard time affording positional goods, like the best hotel rooms.

Just think about the size of this relative impoverishment of Japanese tourists. In PPP terms, Japan’s per capita GDP (World Bank) is $36,426, a normal developed country. What does it mean to lose half your purchasing power? Here are some countries about half as rich as Japan:

Please don’t misunderstand me; I’m not saying that Japan is that poor, the $36,412 figure shows their current PPP income. I’m just trying to give you a sense of how big a drop it is. In fact, at the end of 1993 the yen was quite strong in real terms, so the Japanese seemed rich when they visited Hawaii. But since then, the drop has been precipitous, with Japanese tourists losing over half their purchasing power, relative to Americans.

Please don’t misunderstand me; I’m not saying that Japan is that poor, the $36,412 figure shows their current PPP income. I’m just trying to give you a sense of how big a drop it is. In fact, at the end of 1993 the yen was quite strong in real terms, so the Japanese seemed rich when they visited Hawaii. But since then, the drop has been precipitous, with Japanese tourists losing over half their purchasing power, relative to Americans.

One silver lining is that Japan remains 50% richer than Borat’s home country (Kazakhstan) which has a GDP/person of only $24,228, so I don’t expect to see any Japanese tourists confusing the elevator with their hotel room.

Finally, I get to the point. The PPP theory is pretty elastic, but not infinitely so. The fall in the real value of the yen is probably close to the maximum possible. If Japan were to simply to push the yen back to 125/dollar, and then peg it for several decades, they would likely experience at least as high an inflation rate as the US, probably higher. Because the US is now out of the zero rate trap, I predict our inflation rate will average at least 1.5% over the next few decades. If Japan doesn’t end up with significant inflation, it won’t be because they are unable to do it with monetary policy alone. Rather it would be because they stupidly allowed the yen to appreciate over time. It’s up to them. The US may grouse, but as we showed with the Chinese dollar peg, we are (Thank God!) a paper tiger.

And if I’m wrong, and the real yen exchange rate keeps plunging, then Japanese workers will have Kazakhstani wage by 2040. If those highly productive Japanese workers can’t take market share at Kazakhstani wage levels, then Japan should just fold up shop.

Tags:

8. March 2016 at 16:15

Good post. The yen was much lower in the 1980s and early 1990s, the years just before your chart.

You may have inadvertently cherry-picked years.

Still, a puzzler. Did the Bank of Japan suffocate economic growth in Japan? Seems likely.

But are Japanese living standards really one half of those of Americans?

If the Japanese deliver health care for a much smaller fraction of GDP, and spend a smaller fraction of GDP on national security, and have other less wasteful expenditure, such as security gaurds and school administrators and so forth, perhaps living standards are much closer than official figures would indicate.

Add on, the average Japanese resident has $6,000 in their pocket in paper money. That is cash in circulation in Japan, yen equivalent. Official stats may miss the underground economy.

Many independent stores and restaurants do not take plastic in Japan.

Life in Tokyo, to the casual observer, appears slightly better than life in New York City, Chicago or Los Angeles. Not to mention crime.

8. March 2016 at 16:18

So why the collapse in foreign demand for Yen? Bursting of housing and stock bubble?

8. March 2016 at 16:26

Ben, Good points. Just to be clear, I was not claiming that Japanese living standards were 1/2 US levels, I was suggesting that the purchasing power of Japanese tourists in Hawaii had fallen by more than 50% relative to American tourists. But it started out higher in 1994.

8. March 2016 at 17:47

Fly in Sumner’s ointment: “… as we saw the exchange rate is pretty stable since the end of 1993” – but the graph shows wild sinusoidal fluctuations since 1993; it’s just a coincidence the endpoints ended up only 1% apart. No doubt due to persistent JP central bank manipulation of the exchange rates, to help their exporters (misguided IMO).

Other than that, “excellent blogging” as the turkey farmer B. Cole would say.

8. March 2016 at 18:26

Ray Lopez: yes the turkeys grow up fast, no?

Here is a funny one: I believe my turkeys are of the “slate blue” breed considered a rare Heritage breed in the United States. How they got to Thailand I do not know. I assume the Thai farmers prefer the slate blue as they are low maintenance, and Thai farmers believe that pets and animals should take care of themselves.

8. March 2016 at 19:48

Yikes, Ray actually caught a typo. I should have said the exchange rate was about the same as in late 1993.

8. March 2016 at 22:32

“The yen was much lower in the 1980s and early 1990s, the years just before your chart.

You may have inadvertently cherry-picked years.”

My second thought. First was this is how I think (minus the inflation is innocuous comment), that scared me.

Third was – it is worse because I would have added in interest rates at a 3mo note level. Not going to do the math but the dollar holder of ’93 would have a lot more dollars.

9. March 2016 at 05:18

“Sinusoidal”? Is Ray getting effete on us?

9. March 2016 at 05:25

http://www.japanmacroadvisors.com/page/category/economic-indicators/gdp-and-business-activity/gdp/ [Nice graphics, some economists selling their opinion on JP] (“In a press conference after the preliminary GDP release on February 15, Yoshihide Suga, the cabinet secretary and the key player in the Abe government, blamed the warm winter for the heavy contraction in private consumption. He insisted that the Japanese economy is still cruising ahead.” ) LOL, Baghdad Bob is now a JP cabinet secretary. (“Both growth and inflation have been quite disappointing for Japan in the past two years that the credibility of Abenomics has been badly damaged [sic]. If a recession is to hit the global economy, the damage could be so large that economy participants may completely lose faith in the policy package. “) True, true. Abenomics is dead, our host though still believes in it.

@B. Cole – I let my pet monkey interact with the turkeys today in their pen–they are not heritage but ordinary–and he, less than five pounds and a year old I think, attacked them (chased them). LOL he’s a feisty little fellow, ordinarily he’s fearful of new animals but for some reason he didn’t like the birds. Also I introduced a new turkey pullet to the flock, and after some intervention on my part to make sure the older birds didn’t peck him to death, he seems accepted though roosts lower than the rest and is on the low end of the pecking order. Kind of like new economists when they meet the establishment. Is Sumner establishment? I think so, he’s a big bird.

9. March 2016 at 05:26

These macro bits you do, the global long time-scale ones, with the graphs interpreted with macro’s big ideas taken seriously but not too seriously, finished off with some conditional predictions – they are fantastic.

For me, someone who is interested in macro – long-time reader, bought your book and Nunes’ – but who can’t dedicate all that much time to it, nothing is better than these style posts for stenciling the big broad mental maps of macro history.

Thanks!

Are you really never tempted to bet your ideas at all? Tilt the IRA just a tad in a particular direction?

If in 1982 you knew the monetary theory you do today – not what happened after 1982 – but just the few big ideas about how it all works, would you not have at least suspected financial assets were gonna do pretty well in the next decade?

Re Japan you’ve predicted: either they depreciate to ~125 and ~peg, in which case their inflation rate will approximate ours, or they won’t, in which case PPP is gonna force the Yen to appreciate.

From a foreign investors perspective – American owning the Nikkei – either one looks tolerable.

I’m more interested in the scenario where they peg ~125. The two things that drive fast stock price appreciation in long big bull markets are, a) a rise in P/E’s, and b) a rise in aggregate profit margins. Usually when a country busts out of a failed monetary regime – as Japan may – both P/E’s and profit margins cooperate. And both those things can happen even if the rate of RGDP – which doesn’t matter all that much to P/E’s (empirically) or margins – stays low for demographic reasons.

Thanks again, great post.

9. March 2016 at 05:32

A disclaimer is probably necessary because there’s so many EMH whack-jobs out there and I don’t want to get confused with one:

I think the EMH is almost true but breaks down very occasionally at the largest and tiniest scales, i.e. mispricings too large to be fixed by the fraction of folks able to see them, or those too small (i.e. illiquid stock or bond) to be worth their time.

I’m more sure EMH fails at micro scales because there simply are more opportunities or it to happen, i.e. ~5,000 listed stocks in US.

But I still think there are a handful of macro situations per half century that are possibly exploitable. And I wonder whether Japan might be shaping up that way.

9. March 2016 at 06:29

@brendan – the Japan Short trade is known as a ‘widow maker’ trade. Hedge fund guys like Bass, Einhorn, others have been talking their short book for years to no effect. Further, it’s hard to short a ‘macro’ theme. If you read The Big Short you’ll see the oddball protagonists like Michael Burry et al had a hard time creating a market they could exploit. It wasn’t easy or ‘off-the-shelf’. Off the shelf stuff for retail investors like you and I are usually long or some ETF with fees that make shorting long term impractical.

9. March 2016 at 07:16

Prof. Sumner,

– Why are you so confident the U.S. has successfully escaped the zero rate trap?

– Why are you so confident U.S. inflation will average “at least” 1.5%?

9. March 2016 at 07:21

Scott

You did not cherry pick the data? What did or would you have written in the beginning of 2012 when the Yen could buy a dollar at one half the price as in 1998? Now you want them to lock in their losses at 1.25 yen to the dollar. Is that a free market idea? I thought Europe has shown us that is a bad idea.

I have always looked in awe at the massive fluctuation of the Yen and equally in awe of how Japan survives without great internal turmoil. I have always assumed they are just master currency manipulators, although that is not my point.

Japan has internal government debt at 2x-3x GDP. (That seems like a lot, but what do I know. Krugman says “no problem”—after all they just owe the debt to themselves. I am sure domestic bond holders have a different view on that issue.).

Japan is growing older—one might say they are already old. What has saved them so far is their advanced technology, tight culture, family values, and a willingness to gradually get more poor—although years like 1997-2012 make me wonder how they accomplished gradually getting more poor, given the strength of the currency. Maybe they priced themselves out of the market? But they did grow poorer and will continue to so regardless of what PPP is supposed to imply.

I believe they are getting poorer and that It has to do with their insularity in some way. PPP seems not to be that important—-as hard as it is for me to believe that— except when on vacation (when you seemingly go into “Onion” mode). Certainly your “non cherry picked data” on PPP is not persuasive as to what their future policies should be. Again, I do not think PPP is that important to their future income. They need to either become more productive at a faster rate or grow their population. But that is like wishing on a star.

Their huge debt means they have borrowed from the future. It must be paid back to those who own the debt. It can only be done gradually. Therefore, they will continue to get poorer—and their culture will save them. And if they get to 75 again in dollar/yen the retirees perhaps should move to Hawaii, rather just vacation there. That is a joke. But ……

9. March 2016 at 08:05

@Ray, everything you say is true, but I’m talking about going long the Nikkei.

9. March 2016 at 09:45

brendan, Thanks for the compliments, you have a higher opinion of my forecasting ability than I do. If the yen suddenly rises to 125, Japanese stocks will react before I have a chance to profit from the change. But yes, I am sometimes tempted to try to beat the market, as is everyone. I try to resist the temptation wherever possible.

Travis, Anything is possible, but interest rates are already above the lower bound (which is now below zero) and the market thinks they are headed higher. The Fed says it’s committed to 2% inflation, and I see no reason to doubt their commitment. Actual inflation is trending upwards. Some point to a string of recent misses, but private forecasters also missed, so I think it was an honest mistake.

Michael, You said:

“You did not cherry pick the data? What did or would you have written in the beginning of 2012 when the Yen could buy a dollar at one half the price as in 1998? Now you want them to lock in their losses at 1.25 yen to the dollar.”

I could only find data for Japan going back to 1994, so that’s where I started. I went right up to the most recent data. I would have written something different in 2012, for the obvious reason that the situation was different in 2012. I am describing the situation today.

And no, I don’t want them to peg their currency to the dollar, at 125 or any other rate, I want them to target NGDP. I’m just pointing out that Japan is not stuck with low inflation, they can have the same inflation as the US in the long run, if they wish to do so.

9. March 2016 at 10:06

Brendan,

What I’ve learned about long term forecasting is that a lot can change between now and when I wake up tomorrow.

Michael, couldn’t someone in Japan say they are in awe at the massive fluctuation of the dollar???

9. March 2016 at 11:04

Touche to derivs

I think there may be an appropriate answer to that—-but since I did say “that is not my point” I will—ahem—concede your point. Thanks!

9. March 2016 at 14:09

Scott

The Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis (“FRED”) has great data series. Yen goes back to 1971—-when it cost 350 yen to buy a dollar. The data is downloadable and they seemingly have any time series one can desire.

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/DEXJPUS

9. March 2016 at 15:30

Venezuela at $18k per capita? Um no. Nice to see that data workers just take the GDP in bolivares and blindly multiply by what the Venezuelan gov’t tells them to multiply by. Gawd.

9. March 2016 at 15:44

Wow, Krugman sounds awfully anti-trade in this new post:

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2016/03/09/a-protectionist-moment/?_r=0

And David Henderson addressed Mark Kleiman in a few posts:

http://econlog.econlib.org/archives/2016/03/international_t_1.html

9. March 2016 at 17:56

Thanks Mike, I thought I checked that, but must have forgotten. I’m old enough to remember when it was 350 to the dollar!

Scott, I noticed that too. In fairness, that was from 2014, when oil was at $100.

Thanks Travis, I’ll do a post at Econlog on that in the next day or two.

9. March 2016 at 20:11

Hey Scott,

Long time reader from Saudi Arabia. Mostly enjoy going through the comment section and seeing everyone crap on Ray, and ignore Major Freedom.

Stepping out from lurker purgatory to pick your brain. There’s a couple of different theories stemming from PPP, ex ante has expected inflation as its focal point. In Japan’s case I think the expectation of persistent deflation has been factored in, but doesn’t the market also take into account the massive debt that the Japanese government holds? Do you think that could be one of the main constraints on Yen appreciation?

9. March 2016 at 21:01

@Bob Dylan- how’s the whiskey in Saudi? Or Dubai maybe. Heard the skiing is fabulous there year round, in one of their malls. Your thesis of yen appreciation being constrained by JP debt is not clearly spelled out. Example: JP debt gives 1%/yr nominal in yen. It costs 100 yen to buy this paper. Yen/$ exchange rate is 100:1. Now yen appreciates to 1:1, one yen = $1. JP savers could move their money overseas and get a better return than buying JP paper, is that your idea? So JP paper would be out of demand and fall in price, and/or require JP paper issuers to raise JP nominal interest rates to attract buyers? But consider, if that’s your idea, of ‘financial repression’ along the lines of Regulation Q in the USA: the JP gov’t could make moving money overseas illegal.

@brendan – yes, sorry, I saw that after I posted and could not change my post.

9. March 2016 at 21:23

OT – reading “House of Debt” by Mian and Sufi, both academics. Quite good, it argues against debt in favor of equity, but it has an ideological bias towards believing in ‘nominal wage rigidity’ (sticky wages). But there’s no data to support this claim.

Authors: “We have already mentioned the zero lower bound on nominal interest rates. But two other frictions jump out from the data: wages don’t fall, and people don’t move. A trio of economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco studied wage growth from 2008 to 2012 and found striking results.5 Wage growth adjusted for inflation actually increased annually by 1.1 percent from 2008 to 2011. And this happened despite the highest rate of unemployment in recent history.”

But, look at US inflation by year (BLS)

2008: 3.8%

2009: -0.4

2010: 1.6%

2011: 3.2%

Therefore, 1.1% increase in wages is less than inflation.

I do believe in very very slight wage (and price) rigidity. Very slight. I’ve not seen anybody refute me. Care to try? Sumner ignores me on this issue, just blithely saying that there’s tons of papers supporting sticky wages and prices, without referencing one, and/or pointing to a graph showing asymmetry in wages on the right side of 0%/yr (proves nothing except there’s inflation).

9. March 2016 at 21:35

@myself – do the math, you’ll see I’m right. I even took an IRR of the data so that you started at the end of year 2008 with 103.8 as the starting point (giving the maximum benefit of the doubt to the sticky wage thesis), and the IRR (geometric mean) of inflation was 1.46%/yr, still less than the 1.1 %/yr increase in wages. Ergo, no sticky wages.

My data dump from Excel, self-explanatory:

100 3.8 103.8 -103.8

103.8 -0.4 103.3848 0

103.3848 1.6 105.0389568 0

105.0389568 3.2 108.4002034 108.4002034 1.46%

9. March 2016 at 22:32

Ray,

Actually I gave you a very good argument once for sticky prices using spot market volatility and existing inventories. I’d do it again but 1- the issue interests me only a little and 2- the skiing does happen to be fabulous and the lifts open in an hour and I want breakfast.

9. March 2016 at 23:55

@derivs – enjoy your skiing. I prefer actual data not ‘Austrian type theoretical arguments’. If you have actual data on sticky prices–and not stuff like expired catalog prices but data from liquid markets–then feel free to post here.

10. March 2016 at 02:59

Speaking of Japan:

“BOJ should ease further, says Abe advisor Honda

BY ANDY SHARP

The Bank of Japan should use a combination of a more-negative benchmark rate and enlarged asset purchases “sometime, before long” to help the economy, according to Etsuro Honda, an adviser to Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. “But maybe not next week,” when the BOJ next …”

—30—

Are there any American economists with guts like this?

10. March 2016 at 03:09

“Wage growth adjusted for inflation actually increased annually by 1.1 percent from 2008 to 2011″

10. March 2016 at 05:57

“Venezuela at $18k per capita? Um no. Nice to see that data workers just take the GDP in bolivares and blindly multiply by what the Venezuelan gov’t tells them to multiply by. Gawd.”- Scott H.

Um, yes. Brazil is at 16k. It is almost impossible to Venezuela’s GDP be lower than that.

10. March 2016 at 06:17

Professor, a question a bit irrelevant with the subject, but possibly, indicative for the ways economists think.

Yanis Varoufakis, ex Greek finance minister of Greece, and professor of economics commenting the Cuprus exit from bailout programme posted in his twitter account this formula:

*’Real’ GDP change = (GDP change)/Inflation. When inflation is 0 => GDP change GDP growth in € = -0.68% Simple! *

Two thoughts that also that other people say:

1) This is a way how to calculate real GDP?

In order to get real GDP growth in deflation you need negative nominal growth?

2)And also, RGDP and NGDP is divided by deflator. Deflator can ever be negative?

Cyprus authority for statistics

http://www.mof.gov.cy/mof/cystat/statistics.nsf/index_en/index_en?OpenDocument

10. March 2016 at 06:19

Professor, a question a bit irrelevant with the subject, but possibly, indicative for the ways economists think.

Yanis Varoufakis, ex Greek finance minister of Greece, and professor of economics commenting the Cuprus exit from bailout programme posted in his twitter account this formula:

‘Real’ GDP change = (GDP change)/Inflation. When inflation is 0 => GDP change GDP growth in € = -0.68% Simple!

Two thoughts that also that other people say:

1) This is a way how to calculate real GDP?

In order to get real GDP growth in deflation you need negative nominal growth?

2)And also, RGDP and NGDP is divided by deflator. Deflator can ever be negative?

Cyprus authority for statistics

http://www.mof.gov.cy/mof/cystat/statistics.nsf/index_en/index_en?OpenDocument

10. March 2016 at 06:21

The formula is:

<'Real' GDP change = (GDP change)/Inflation. When inflation is 0 => GDP change

10. March 2016 at 06:22

Hi Scott,

I’d be curious to know your opinion on this: “In light of cuts to the growth and inflation outlook, the ECB announced on Thursday that it had cut its main refinancing rate to 0.0 percent and its deposit rate to minus-0.4 percent.

It also extended its monthly asset purchases to 80 billion euros ($87 billion), to take effect in April. In addition, the ECB will add corporate bonds to the assets it can buy — specifically, investment grade euro-denominated bonds issued by non-bank corporations. These purchases will start towards end of the first half of 2016.”

Is the ECB on the right track or are they doing as little as possible to give the appearance of taking “strong action”? A small post on this would be great.

10. March 2016 at 06:22

Can’t post formula

‘Real’ GDP change = (GDP change)/Inflation. When inflation is 0 => GDP change <0 – a case of continuing recession.

10. March 2016 at 06:42

@Postkey, regarding wage inflation: thanks, I missed that on the OP. However, I dispute there’s sticky wages and don’t trust the author of House of Debt (he’s a Keynesian btw, where sticky wages is a key assumption in that worldview). In researching this topic, I reviewed the BLS website and I found their data for wage growth only goes back to 2012 (“With the enactment of the 2011 Federal budget, the Locality Pay Survey (LPS) portion of the National Compensation Survey (NCS) was eliminated”). Further, the BLS breaks down stuff by industry and by state in a very detailed manner. So, surfing the net, I found this passage which supports my OP that there’s no sticky wages in the US:

http://www.businessinsider.com/average-wage-growth-in-the-us-2013-8 “Between 2002 and 2012, wages were stagnant or declined for the entire bottom 70 percent of the wage distribution. In other words, the vast majority of wage earners have already experienced a lost decade, one where real wages were either flat or in decline.”

US inflation between 2002 and 2012 was, according to the BLS, 2.47 %/yr (geometric average). Yet wage inflation was “stagnant or declined” for the bottom 70%. Thus, if there’s sticky wages at all, it’s only for the top 30% of wage earners. I doubt that would be the case but I don’t have any further data.

This is just one example. Sumner might object (I suspect he would) that sticky wages means wages don’t adjust instantly, but take a quarter or two or more to do so (I’d like to know what his time period for lag is; I’m just guessing his views). Thus a more detailed analysis than this one is needed. But, to date, Sumner’s not communicated why he believes in sticky wages, so there’s no telling what data he believes in. But based on my analysis, there’s no such thing as sticky wages. Prove me wrong.

10. March 2016 at 08:23

Bob Dylan, Honored to have you comment here. You’d think the big debt would create inflation expectations (fiscal theory of the price level) but it doesn’t seem to. Perhaps because people don’t expect Japanese interest rates to bounce back up.

Ray, You took wage growth adjusted for inflation, and subtracted out inflation??

Double face palm.

Alex, It should be MINUS inflation.

Tyler, Check my new post.

10. March 2016 at 10:14

@Ray.

‘I’cannot ‘prove you wrong’!

Maybe you can be convinced by Mary Daly, Bart Hobijn, and Brian Lucking?

“Despite a severe recession and modest recovery, real wage growth has stayed relatively solid. A key reason seems to be downward nominal wage rigidities, that is, the tendency of employers to avoid cutting the dollar value of wages. This phenomenon means that, in nominal terms, wages tend not to adjust downward when economic conditions are poor.”

http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2012/april/strong-wage-growth/

10. March 2016 at 10:38

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2015/02/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=64&pr.y=8&sy=1994&ey=2014&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=158%2C111&s=NGDPDPC&grp=0&a=

10. March 2016 at 10:57

Thanks HW, I always have trouble finding that sort of data.

10. March 2016 at 12:47

Ray,

My argument is only about stickiness at the retail level. If that’s not where you are looking than it is not relevant. But prices are clearly sticky at the retail level.

10. March 2016 at 19:57

@Postkey -thanks. My rebuttal is lifted from the paper you referenced.

“This phenomenon has affected a broad range of workers during the recent period. Figure 4 plots the share of workers receiving no wage change by education. Less-educated workers have historically been more likely to get no yearly wage change. Recently though, the percentage of workers with no wage change has increased markedly at all education levels. This contrasts with the business cycles of the early 1990s and 2000s, when more-educated workers were shielded to a greater extent from increases in nominal wage rigidities. In fact, in the recent period, zero wage changes increased almost as much for college-educated workers as for workers with less than a high school education. That has not been seen in any other period in our sample, suggesting that a broad range of employers in a variety of sectors might feel pressure to cut wages, but are unable to do so because of downward nominal wage rigidity.”

Read that carefully. Though the language is horribly ambiguous, it’s clear that the “nominal wage rigidity” (sticky wages) is a RECENT PHENOMENA. In early business cycles (“early 1990s and 2000”, and possibly even before, which is not clear), there was NO STICKY WAGES. The higher educated workers, presumably non-unionized, had flexible wages.

So are we to say that Sumner’s sticky wages hold true only for ‘today’s recession’ since 2008? If that’s Sumner’s position, I will gladly agree to it.

Jury still out on proving sticky wages. Show me the evidence.

@Derivs – thanks, I agree that retail prices can be sticky, due to thinks like local market power, be it from retail gasoline (which depends on refineries which have slight monopoly power, as is well documented, hence ‘sticky going down’ prices, but not going up of course), or from local monopolies like cement/gravel companies (notoriously well known to have local monopolies, as their products are hard to ship). But most prices in liquid markets are not sticky. Is Sumner’s NGDPLT good only for today’s recent recession (see my answer to Postkey) and for local gravel companies? OK I concede that point if so.

@Sumner – your readers are trying to defend you, but you would do better to speak for yourself. Where’s your data for sticky prices and wages? Run away.