Extreme events generally have multiple causes

There were a number of good responses to my previous post, which asked why the death rate in Italy was 100 times higher than in Scandinavia. One answer was that Italy got its cases earlier, and thus patients have had more time to get seriously ill. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the ratio has already fallen to more like 50 to 1.

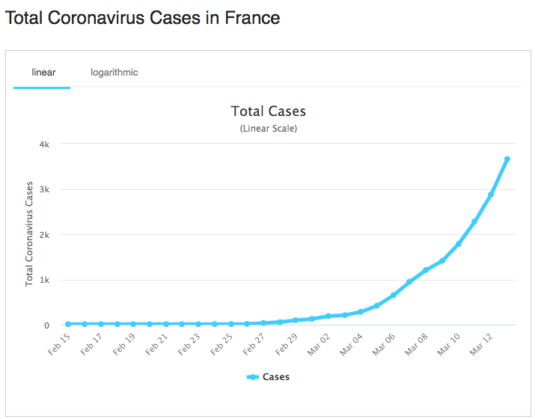

But that’s probably not the entire story. France and German cases track each other extremely closely:

And yet France has 91 deaths while Germany has just 8. In this case, I assume that France has a larger share of infected people who are over 70 years old.

When comparing Scandinavia and Italy, I suspect at least three important factors:

1. The Nordics who are infected tend to be healthy people who traveled to Italy, whereas the Italian deaths are mostly among elderly people who are less likely to travel.

2. Italian people infected with the virus have had the virus for a longer period of time, as noted above.

3. A larger share of infected people in Scandinavia have been tested.

Another possible factor is worse medical care in Italy due to hospital overcrowding, although I suspect that’s only a marginal factor thus far.

The lesson here is that extreme events usually have multiple causes. This is also true in economics. If extreme events had single causes, then presumably they’d occur much more often. In my book on the Great Depression I argued that there were multiple policy errors, on both the supply side and the demand side.

People younger than me won’t remember Beamon’s Leap, but I do:

While Beamon received mostly accolades, there also were detractors. The critics harped on the conditions — a following wind of 2.0 meters per second (the maximum allowable velocity for a record), a lightning fast runway and, most important, the thin air of Mexico City. Beamon’s defenders point out that the other competitors, which included the world record co-holders, had the same factors going for them and they didn’t jump close to Beamon.

What a killjoy!!

PS. Trump should immediately remove the travel ban from China. We are now in far more danger from visits by Canadian tourists than visits by Chinese tourists. This should be done even if the original ban was entirely justified (which seems plausible.)

PPS. Over at Econlog, I discuss Boris Johnson’s recent policy changes, and also explain my claim that the US will never experience hundreds of thousands of deaths from coronavirus.

PPPS. It’s early, but there is some evidence that Norway and Denmark are beginning to get a handle on the crisis.