John Roberts on monetary reform

David Beckworth has a new podcast where he interviews John Roberts, who spent 36 years at the Federal Reserve Board as a macroeconomist. At one point in the interview he was asked about how the Fed should tweak its policy regime in the next review period (which is scheduled for 2024):

Roberts: So I think in that statement of longer-run goals, that constitutional document, I would keep, for the reasons I was just saying, the shortfalls language on maximum employment. But I’m not sure I would keep the shortfalls language on the average inflation targeting. My reasoning is that, if you think about it, that puts an upward bias to inflation. When they adopted that, it seemed like it was a good idea to have an upward bias on inflation, because their concern was getting stuck in a low inflation world because of the low interest rates. Today, it doesn’t look like we have a problem with inflation never being able to be high. It looks like that’s perfectly possible. So I don’t think, from today’s perspective, they need that asymmetry in the constitutional document anymore.

Roberts: And then in terms of if they ever do hit the lower bound again, what statement language they should use… So I think in retrospect, it looks like having those two criteria for liftoff, both the maximum employment and the price level-related one, led to monetary policy being too loose for too long. So a really simple change in my view would be to change the “and” in that conditionality to an “or.” So you would say then that, “We will keep the federal funds rate at the effective lower bound until either we’ve achieved maximum employment or some kind of average inflation targeting criterion has been reached.” So that would’ve stood them in good stead this last time around, because by the middle of 2021, they had already made up the shortfall in prices. So that promise would not have gotten in the way this last time. And it would’ve stood them in good stead in the previous cycle where it took a long time to get to maximum employment and inflation kept undershooting. So it would work for each of the last two cycles. Who knows? Maybe some other thing will come up that would make it not work in the future, but at least, it would have worked, I think, in the last couple of times. So the tweak there would simply be to change “and” to “or.”

Given his career path, I imagine that Roberts has much more insight than I do into where policy is headed. While these are his own views, I suspect the final decision will be not too dissimilar to his proposal. After all, the Fed knows they erred in allowing inflation to get too high, and thus the obvious place to adjust FAIT is in making it symmetrical, at least for inflation.

It’s unfortunate that the Fed is probably unwilling to adopt NGDP level targeting. I suspect they believe that their mandate forces them to target inflation and employment, but that is not the case. The mandate is the goal of policy; if the Fed believes (as I do) that NGDPLT is the best way to achieve that goal, then NGDPLT is fully consistent with the dual mandate.

The change from “and” to “or” does make the employment part of the regime less bad, but there’s still room for mischief. And it’s a mistake to make any promises about the path of interest rates, including a promise not to raise rates until some threshold for inflation or employment is met. To see why, consider Roberts’ explanation of what went wrong in 2021:

So they said that they would keep the funds rate at zero until the unemployment rate reached their estimate of maximum employment. They didn’t spell that out, but that could well have been, say, 3.5% unemployment because that’s where they were pre-COVID and that was not inflationary.

He’s probably right about the 3.5%, but of course that’s a terrible way to do policy. During the 1970s and early 1980s, the unemployment rate was far about 3.5% and yet we had a severe inflation problem. The Phillips Curve is not a reliable guide for policymakers.

Again, the Fed needs to stabilize NGDP growth along a level path. All policies that lead to highly unstable NGDP will fail to stabilize the macroeconomy.

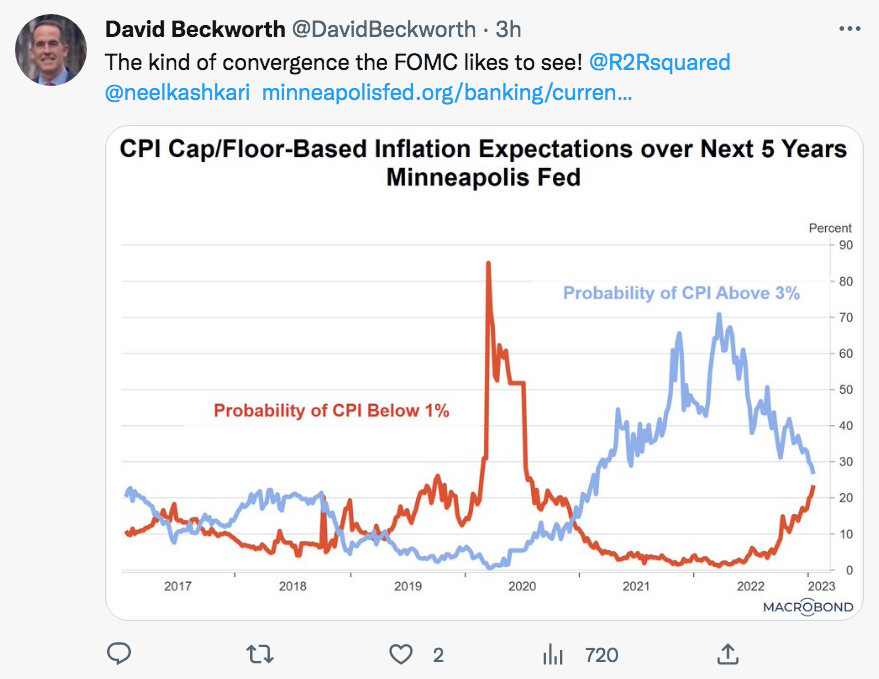

PS. This David Beckworth tweet caught my eye:

I mostly agree, but would delete the phrase “kind of”. The Fed wants to see convergence, but the kind of convergence they’d like to see is down below 10% chance of each type of overshoot, not roughly 25% chance of each.

PPS. In a new article I wrote for the National Review, I point out that low and stable NGDP growth is a necessary and sufficient condition for the Fed to achieve its policy goals:

The Fed does not currently target nominal spending. But as a practical matter, the Fed cannot achieve its goal of low inflation and high employment without stable nominal-spending growth. Whenever spending growth is far below 4 percent, unemployment will rise sharply. Whenever it is far above 4 percent, inflation will rise. Because spending growth is the sum of inflation and real GDP growth, it is the best single indicator of the Fed’s performance.

A policy target of 4 percent spending growth is much more credible and transparent than a vague policy aimed at 2 percent inflation and high employment. How should high employment be defined? The Fed doesn’t tell us. How does it balance the goals of avoiding high inflation and encouraging high employment? The Fed doesn’t tell us. What does it do if it misses a policy goal? Again, the Fed doesn’t tell us.

Read the whole thing.

PPPS. New new NGDP figures show 7.3% growth over the past four quarters, which is far too high. I warned you all back in early 2022 not to assume that just because the Fed had embarked on a series of rate increases they were tightening monetary policy. Interest rates are not monetary policy. Money was extremely loose in 2022.

When will we ever learn?