Time to pay the piper? (part 2)

Over at Econlog, I have a post entitled “Time to pay the piper?“, which looks at the cost of recent monetary policy. That cost actually doesn’t concern me too much, as from the perspective of the consolidated government balance sheet it’s mostly a wash. (That’s not to deny that QE went overboard. In retrospect, policy was clearly too stimulative.)

My bigger concern is fiscal policy. While I failed to correctly predict the upsurge in inflation, I nonetheless did oppose the Covid fiscal stimulus, albeit for other reasons. Here’s what I said in 2020:

With the seemingly endless stimulus now coming out of Washington, it’s time to revisit the question of whether deficits matter. In recent weeks, I’ve seen lots of pundits say that government spending is virtually costless, as interest rates are close to zero. There are two flaws with this argument.

In other posts I pointed out that if you run up a large national debt at the zero lower bound, then you expose your country to the risk of ballooning financing costs if interest rates rise to more normal levels. I did not actually expect rates to rise as much as they have, but then I didn’t expect the Fed to abandon average inflation targeting and start running highly inflationary monetary policies. And yet even though I didn’t expect much higher interest rates, I did not believe that fiscal stimulus was worth the risk.

When I spoke of “future tax liabilities”, I got a lot of pushback from people suggesting that we would never need to repay our national debt. That’s true in a sense, but very misleading. Even if we never actually repay the debt, it still must be serviced. Because of rising interest rates, we’ll have to pay higher (distortionary) taxes in future years to pay interest on the reckless fiscal stimulus of the Trump/Biden administrations. The UK is facing the same issue.

It was possible to view the fiscal stimulus during the Great Recession as a one time thing. We usually don’t have recessions that large. But then Covid comes along and we get a far bigger stimulus. Again, we are told it’s a one time thing. Then a massive bailout of student loans, and a promise we’ll never, ever do anything like that again. UK taxpayers are being told they must now bail out energy consumers, And today we’re told that hurricane Ian will be the most costly ever. Doesn’t it seem like governments are more and more willing to write massive checks whenever people are even slightly inconvenienced? If so, is it any surprise that markets are pricing in higher real interest rates going forward? Our deficit projections are unreliable.

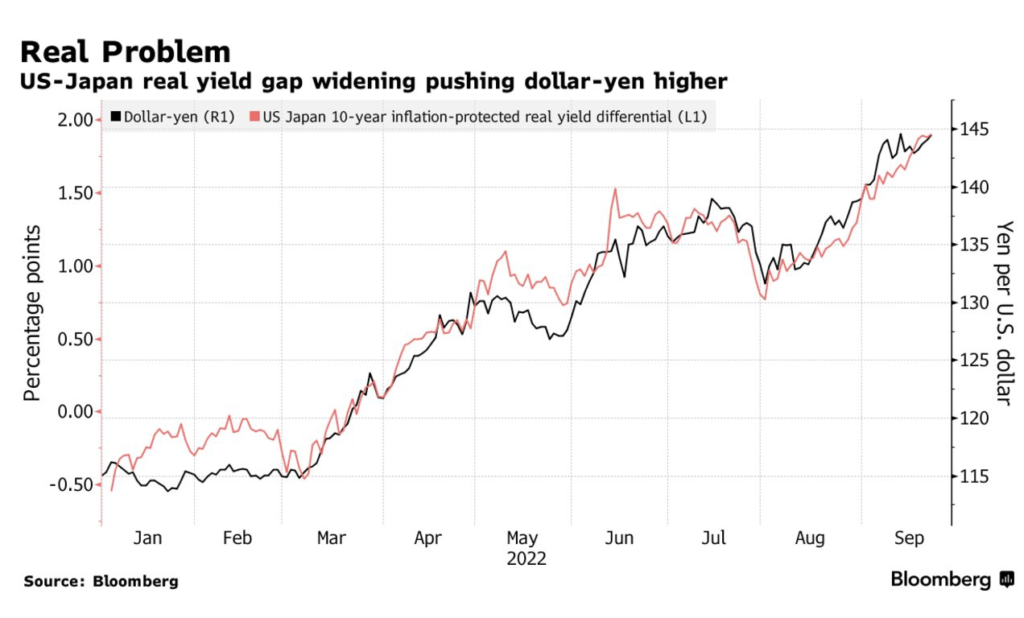

PS. I’ve been asked about the recent market turmoil in the UK, but I don’t have any good answers. The rise in the UK’s real interest rate may partly reflect the recent stimulus announcement. But as many have pointed out, that would normally lead to currency appreciation. Furthermore, real rates have risen sharply in the US, so it seems that global factors are also a factor.

Market indicators continue to show very little default risk for UK public debt, so that doesn’t seem to be the issue. A more plausible risk is the BoE being pressured to monetize the debt. But inflation spreads did not rise during the period when the pound plunged. And the pound seemed to rally on monetary stimulus. So I’m at a loss to explain the situation.

I had a very negative view of Boris Johnson, who promoted a foolish Brexit policy and ran large budget deficits. But while Brexit tended to depreciate the pound, that factor was already priced in before the recent market turmoil. I’ll take a wait and see attitude on Truss, who seems likely to continue the UK’s overly expansionary fiscal policy. To her credit, she does have a number of excellent pro-growth policy initiatives in areas such as housing, investment, and immigration. Let’s see what she is actually able to deliver.