Ed Nelson on Milton Friedman

One of my favorite David Beckworth podcasts is his interview of Ed Nelson, who has recently published a book on Milton Friedman (which I plan to read soon.) Here Nelson discusses how Friedman responded to Sargent and Wallace’s Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic paper:

And, it’s a good news for monetarists because you can separate monetary and fiscal policy, even with fiscal policy running large deficits. And so Friedman argued that as a practical manner, other than the early 80s, it was the case that US history was characterized by R being lower than little g, growth rate of government spending. So when you have that, you had a situation in which you can run deficits, you can accumulate debt and you’ll still have debt to GDP, public debt to GDP, often tending to decline. So he regarded that like the practical case. That was his answer to Sargent and Wallace. And in fact, if you look at the Gilder and Fisher textbooks from the 80s, the r less than g edition, and this is something that, has had life breathed into it by Olivier Blanchard’s paper, it’s something that’s been a textbook point for a long time. And Friedman made the point in 1987. And of course it’s basically implicit or explicit in Sargent and Wallace, but anyway, it wasn’t what Sargent and Wallace pushed, but it was what Friedman pushed when he read Sargent and Wallace that, “You will be able to separate monetary and fiscal policy because R is less than G.”

Today, R (interest rates) are even further below g (economic growth.)

A lot of nonsense has been written to the effect that “there is no such thing as a money multiplier”. Nelson sets the record straight:

And the reason he thought an M2 target was feasible is that he thought that the monetary base could be used to manage M2. He believed that there was a ceteris paribus money multiplier relationship between the monetary base and M2. The monetary multiplier is, again, something that gets a lot of trash talking among modern day economists and people who say, “all textbooks are all wrong about the money supply process.”

I think that that is really doing a disservice to the idea of ceteris paribus. Because if you just look at a world without interest on reserves or without a lot of the complications, there is a logic why a change in reserves would lead to a change in deposits. You can add all sorts of bells and whistles to the money supply function, but that’s the basic message that I think is valid. And so, he was arguing, you should be able to control M2, by offsetting with open-market operations factors affecting the money multiplier. So, you can argue that that was a sense of fine-tuning prescription, the fine tuning would be getting an M2 target, but he believed there was a fairly reliable relationship between the monetary base and M2 and after the 1990s, certainly that was quite accurate.

Friedman used M2 as an intermediate target in roughly the same way as I use NGDP futures prices as an intermediate target. The correct criticism of the money multiplier is that it is not particularly useful, even without IOR, because targeting M2 is not a good idea.

Another common misconception is that monetarists (wrongly) assumed that the actual velocity of circulation was constant. Not so:

Beckworth: And I think he would argue, and correct me if I’m wrong here, he would argue that if the Fed had done this, if the Fed had successfully targeted, say, M2 this whole period, this whole time, then velocity would have been more stable. Is that fair? And therefore this breakdown in the money demand relationship with income would be less of an issue.

Nelson: That’s right. He believed, for example, in the 1930s, particularly that the big fall in velocity, and it was a big fall in the velocity, even though the money and nominal spending had a big relationship. It was a big fall in velocity, but he thought that was due to big uncertainty engendered by the monetary and economic collapse. So he thought that velocity fluctuations often were triggered by monetary instability. And that certainly is something that will be widely shared when it comes to hyperinflation which is well-known in term, inflation engenders big increases in velocity.

PS. In the National Review, David Beckworth pushes back against the view that big deficits will lead to high inflation

PPS. Matt Yglesias has a very clear explanation of why NGDP is a better target than inflation.

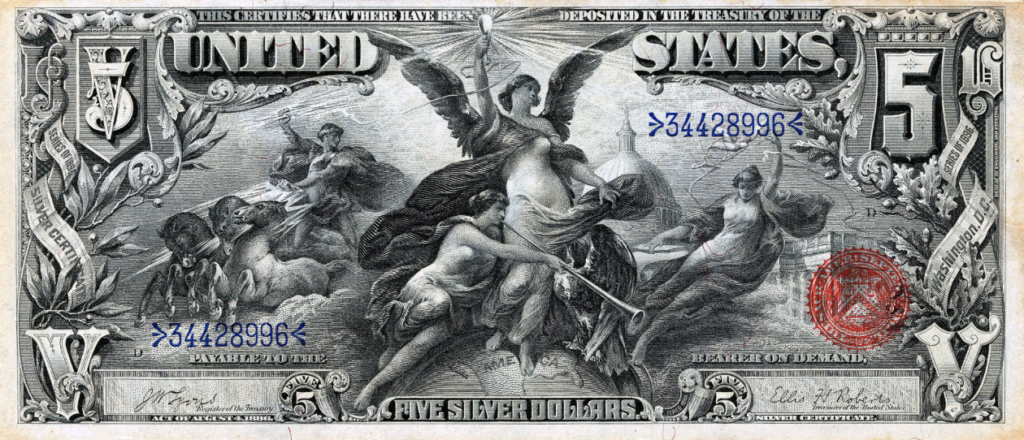

PPPS. George Selgin has a very informative post on banknotes during the 19th century. Here’s the image he should have used for government money porn: