1. Don’t rely on others:

“I don’t think any country has a perfect record,” Bill Gates said in a recent interview. “Taiwan comes close.” . . . Taiwan seems to have followed the model recommended by disaster expert Vaughan: It doesn’t expect infallibility from its leaders. Instead, Taiwan makes sure that its health institutions are hyper-vigilant about epidemic risks. After the SARS epidemic of 2003, Taiwan set up an interlocking set of agencies geared toward the early detection of pandemics and bioterrorism. If a threat is detected, containment plans and supply stockpiles are ready. That process starts at the bottom, not the top.

Vaughan and other researchers note that complacency is usually fed by groupthink. At a time when China and the World Health Organization were downplaying the coronavirus threat, it was easy for world leaders to believe that everything was under control. Meanwhile, China has used its influence to keep Taiwan out of the WHO and other international organizations, and Samson Ellis, the Taipei bureau chief for Bloomberg News, believes that Taiwan’s isolation from WHO paradoxically helped the country by forcing it to rely on its own judgment on health issues.

“Taiwan knows it’s on its own,” he says.

In January, while other countries were trusting the WHO’s bland assurances, Taiwan was already turning away cruise ships and performing health checks at airports. Taking early action against COVID-19 meant defying a consensus shared by much of the world. The country’s public-health institutions were designed to be sensitive to even faint signs of trouble and to guard against optimistic biases.

Read the whole things (by James Meigs.) Taiwan is rapidly becoming one of my very favorite countr . . . er . . . places.

They also make outstanding films.

2. Bill Gates has been great, but here he’s a bit too soft on China:

He is impatient too about attacks on China for its lack of openness about Covid-19 and particularly its reluctance to allow non-Chinese experts to investigate the origins of the coronavirus outbreak in the city of Wuhan. “Sure, they should be open, but what is it that people are saying they’re not being open about? Every country has a lot you can criticise,” he said.

“Most people, whenever something new comes along, they take their classic criticisms of that country and just repeat them. But here we should get concrete. I don’t see any deep insights that are missing in terms of the origin of the disease that somebody is holding something back.”

I have a more centrist position on China—harshly critical of their government’s initial cover-up, which imposed great hardship on the Chinese people, and (like Bill Gates) dismissive of Westerners who want to blame our current policy failures on China.

3. Fortunately, while the US government tries to launch a cold war against China, private sector actors are trying to work with Chinese scientists in a constructive fashion:

US scientists are working with China to investigate the origin of coronavirus, despite criticism from the Trump administration that Beijing is failing to co-operate with outsiders to stem the disease.

Ian Lipkin, director of the Center for Infection and Immunity at the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University, said he was working with a team of Chinese researchers to determine whether coronavirus emerged in other parts of China before it was first discovered in Wuhan in December. The effort relies on help from the Chinese Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

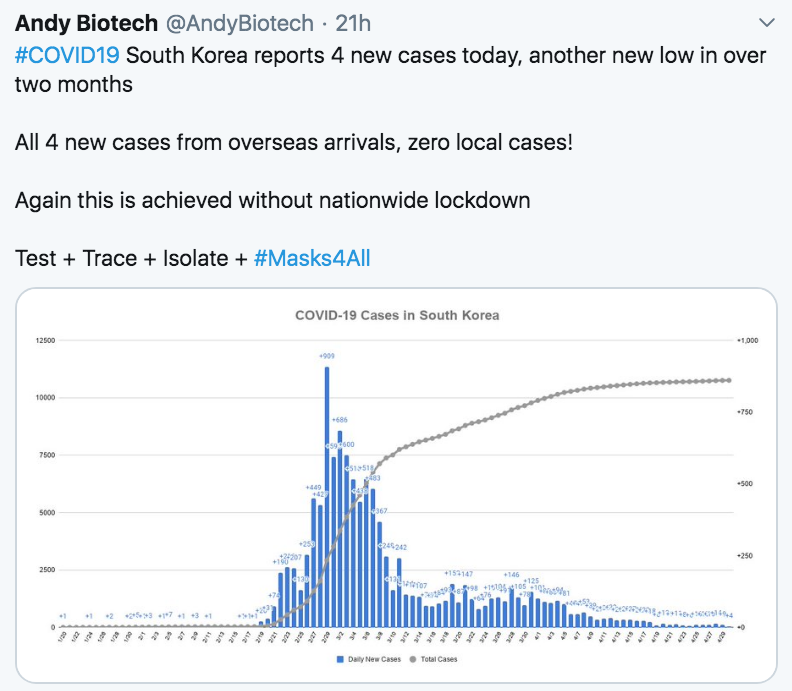

4. This is great news:

After Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston began requiring that nearly everyone in the hospital wear masks, new coronavirus infections diagnosed in its staffers dropped by half — or more.

Brigham and Women’s epidemiologist Dr. Michael Klompas said the hospital mandated masks for all health care staffers on March 25, and extended the requirement to patients as well on April 6.

But they should have started on March 1st.

5. We have lots of testing capability that is not being used due to regulatory barriers:

As the United States struggles to test people for COVID-19, academic laboratories that are ready and able to run diagnostics are not operating at full capacity.

A Nature investigation of several university labs certified to test for the virus finds that they have been held up by regulatory, logistic and administrative obstacles, and stymied by the fragmented US health-care system. Even as testing backlogs mounted for hospitals in California, for example, clinics were turning away offers of testing from certified academic labs because they didn’t use compatible health-record software, or didn’t have existing contracts with the hospital. Researchers warn that if such hurdles remain, labs trying to join the effort to fight coronavirus might end up spinning their wheels.

This is insane. We need deregulation and we need more price gouging.

6. It’s possible that the virus escaped from a lab, but it’s about a million times more likely that it infected a random person in Southeast Asia:

Next, he says, consider the data he’s collected on people near bat caves getting exposed to viruses: “We went out and surveyed a population in Yunnan, China — we’d been to bat caves and found viruses that we thought could be high risk. So we sample people nearby, and 3 percent had antibodies to those viruses,” he says. “So between the last two and three years, those people were exposed to bat coronaviruses. If you extrapolate that population across the whole of Southeast Asia, it’s 1 million to 7 million people a year getting infected by bat viruses.”

Compare that, he says, to what we know about the labs: “If you look at the labs in Southeast Asia that have any coronaviruses in culture, there are probably two or three and they’re in high security. The Wuhan Institute of Virology does have a small number of bat coronaviruses in culture. But they’re not [the new coronavirus], SARS-CoV-2. There are probably half a dozen people that do work in those labs. So let’s compare 1 million to 7 million people a year to half a dozen people; it’s just not logical.”

In addition, a cover-up is very unlikely:

Carroll, the former director of USAID’s emerging threats division who also spent years working with emerging infectious disease scientists in China, agrees that there’s no evidence the Chinese researchers were working with a novel pathogen. His reasoning? He would have heard about it.

“The reason I’m not putting a lot of weight on [the lab-escape theory] is there was no chatter prior to the emergence of this virus to a discovery that would have ended up bringing the virus into a lab,” he says. “And if nothing else, the scientific community tends to be very gossipy. If there is a novel, potentially dangerous virus which has been identified, circulating in nature, and it’s brought into a laboratory, there is chatter about that. And when you look back retrospectively, there’s no chatter whatsoever about the discovery of a new virus.”

And if these viruses infect millions of people each year, then why is it so important if that person happens to work in a lab?

7. I usually agree with Ramesh Ponnuru, but here I think he’s being a bit too kind to the US:

America Isn’t Actually Doing So Badly Against Coronavirus

I agree with Ponnuru that it’s silly to focus on Trump, as if another president would have made a big difference. And I agree that it was almost inevitable that our response would be messy and full of mistakes (as James Meigs pointed out in the article I linked to on top).

But let’s not mince words; we (including myself) have done very poorly. We have 4% of the world’s population and 27% (and rising) of fatalities. Even accounting for errors in the data, we are doing much worse than average. Yes, some countries have done even worse, but that just means they’ve also done poorly.

Many countries have done far better than the US. If we do far worse than South Korea, Australia, Vietnam, Taiwan, Japan, Germany and Austria, I don’t get much consolation from the fact that we are doing better than Italy, Spain, France and the UK. We are supposed to be a global leader in technology and state capacity.

I also think this is a bit too optimistic:

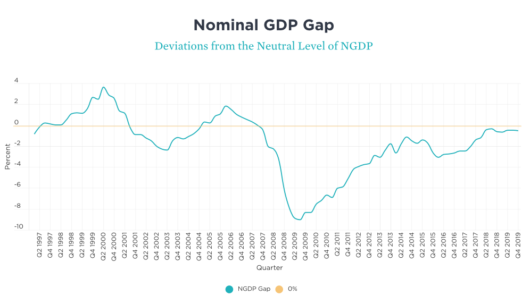

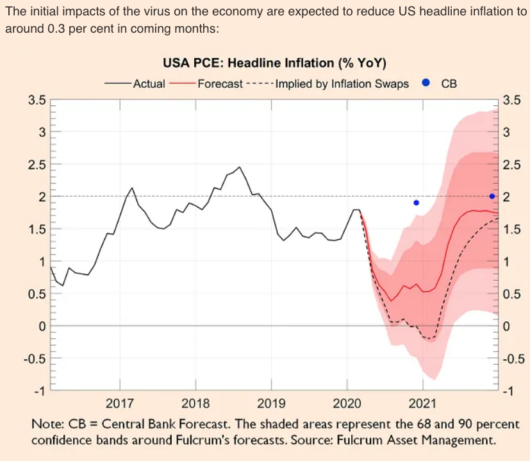

The Federal Reserve cut interest rates and expanded lending facilities, moving, like Congress, faster than it had during the financial crisis of a dozen years ago.

Yes, they’ve done some very good things, and this crisis is more severe than 2008. But the bottom line is that we are currently making the same mistakes as in 2008, failing to adopt level targeting and allowing price level/NGDP expectations for 2022 to fall sharply. Level targeting isn’t an extreme idea; people both inside and outside the Fed know it’s the right thing to do right now. It’s just institutional inertia holding them back.

(I.e., if we already had level targeting there is zero chance the Fed would switch back to growth rate targeting right now. That’s what I mean by “inertia”.)

8. On the lighter side, I just LOVE Japan:

Hokkaido has now had to re-impose the restrictions, though Japan’s version of a Covid-19 “lockdown” is a rather softer than those imposed elsewhere.

Most people are still going to work. Schools may be closed, but shops and even bars remain open.

Bars open, schools closed. I recall on my 2018 visit to Japan that you could buy booze from a vending machine: