The Black Death killed 1/3 of all the people in Europe. The demand for almost every single commodity probably fell, in the sense that demand curves shifted to the left. Supply curves also shifted to the left, and hence relative prices stayed about the same, on average. (In a supply and demand diagram, the “price” on the vertical axis is the relative price, the price relative to the overall CPI.)

And yet the Black Death probably had little or no impact on aggregate demand. How can that be? There were far fewer people, and the demand for virtually every single commodity fell. Why wouldn’t aggregate demand also fall?

Aggregate demand is a horrible term for the concept that economists use in macro 101. It has absolutely nothing to do with “demand” in the ordinary sense of the term. I wish it were called “nominal expenditure”. The “price” on the AS/AD diagram is the nominal price level, not the relative price of a single commodity.

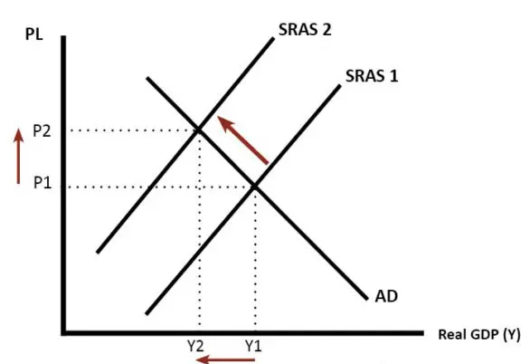

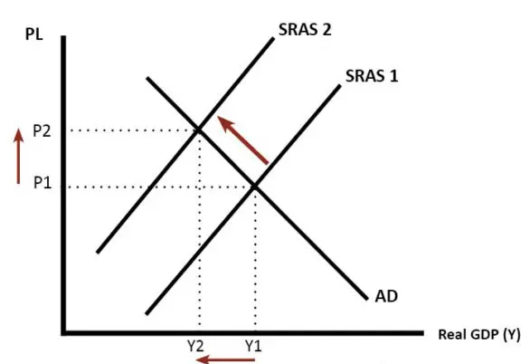

The Black Death did not kill money, so the (commodity) money supply was presumably unchanged. If might have reduced AD by reducing velocity, but I doubt it had much impact. We know that the Black Death increased the price level in Europe, and it’s likely that it reduced real GDP. The AD curve probably didn’t shift very much in response to this plague. Here’s what happened:

When average people think about macro, they tend to conflate “aggregate demand” and “quantity of goods and services purchased”. Even if there is no change in aggregate demand, the quantity of stuff that people buy at stores will tend to fall when AS falls (as in the figure above). But that’s a decline in equilibrium quantity; it’s not a decline in AD.

Monetary policy determines AD. The Economist recently had this to say:

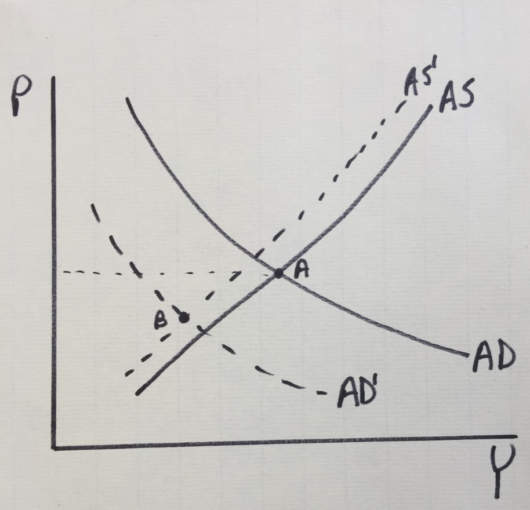

In practice, the distinction between shocks to demand and those to supply is fuzzy. In a paper published in 2013 that revisited the era of stagflation, Alan Blinder of Princeton University and Jeremy Rudd of the Federal Reserve argue that supply alone cannot explain the soaring unemployment of the 1970s. In fact, they say, price increases had demand effects that mattered more. They raised uncertainty, reduced households’ disposable income and eroded the value of their savings.

Actually, aggregate demand (NGDP) in the US rose at about 11%/year from 1971-1981, due to easy money (despite 15% interest rates!) People were spending money like crazy. So the high unemployment was not primarily caused by a demand shortfall. In my view, the natural rate of unemployment rose during the 1970s. Spikes in unemployment in late 1974 and the spring of 1980 were caused by brief declines in AD (NGDP growth).

PS. Narayana Kocherlakota may not be right, but his recommendation is probably “less wrong” than doing nothing:

My benchmark forecast is that the U.S. economy will remain resilient to these forces. But there is a substantial risk that such a forecast could be wrong. One possible strategy is to wait until there actually is a slide in the economy before easing interest rates. But rates are still only a little above zero and so the Fed has few tools available to offset adverse shocks. In this situation, a basic precept of monetary policy is to keep the economy as healthy as possible in advance of downturns. As New York Federal Reserve Bank President John Williams explained in a speech last year, that means cutting interest rates in a pre-emptive fashion when threats to growth become more pronounced. Of course, it was exactly in response to the increase in global downside risks that the Fed cut interest rates by 75 basis points, or three-quarters of a percentage point, in 2019.

The Fed’s rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee holds its next meeting on March 17-18. I don’t think that the FOMC should wait that long to deal with this clear and pressing danger. I would urge an immediate cut of at least 25 basis points and arguably 50 basis points. That’s a cheap insurance policy for the economy that the Fed shouldn’t pass up.