Ha ha ha

It’s easy to ridicule economic ideas. Nathan Lewis did a Forbes piece back in 2016 that ridiculed both traditional and market monetarism. Potential Fed nominee Judy Shelton called Lewis’s article “brilliant analysis”.

Over at Econlog I defended Milton Friedman from Lewis’s attacks. At one point in an earlier Forbes post Lewis wrote the following:

Bitcoin is an entertaining little trading sardine, which might have within it some templates for use in the creation of a much better currency unit. But, to propose this for the U.S. dollar? And make it a Constitutional Amendment?

Ha ha.

Ha ha ha.

Friedman was a dope. It’s funny that decades have gone by, and practically nobody has figured this out.

I think you get the idea. It’s Forbes.

In the article Shelton praised, Nathan Lewis points to an important and not well understood flaw in NGDP targeting; inflation would move inversely to RGDP growth. (Yes, I’m being sarcastic.) Perhaps this was the part that Shelton thought was brilliant:

With a stable currency, “real” GDP might be -2.0%. However, the Federal Reserve would – automatically – increase the monetary base such that this is magically turned into an NGDP of 3.65%. In other words, the GDP deflator might be +5.65%. That would be a pretty big move for a broad, slow-moving price index like the GDP deflator. It would probably require a substantial decline in dollar value, on the foreign exchange market for example.

Yup, that’s what happens under NGDP targeting, indeed that’s the whole point of NGDP targeting. The idea is to allow real shocks to change real GDP, but not magnify the effect unnecessarily by having NGDP change as well, causing lots of unnecessary unemployment. So what’s wrong with the idea? Lewis doesn’t say. He seems to think the fact that inflation would fluctuate is an argument, even though he’s later downright contemptuous of inflation targeting. Indeed he favors a gold standard, which is a regime that would also allow the inflation to fluctuate, in this case in response to changes in the supply and demand for gold. In the end, Lewis doesn’t even present any arguments against the claim that NGDP stability is better than price stability, he simply denies it.

Lewis continues:

Then, there’s the possibility that the “NGDP futures market” could be manipulated by large financial interests. Sumner assures us that this is impossible, because some other academics wrote a paper.

I’ll come back to this later, but first let’s have some fun with Lewis’s preferred policy, the gold standard:

The gold standard has an awesome track record of real-life success over a period of centuries. That’s why conservatives traditionally supported it.

So we are supposed to attach our money to a commodity that has wild swings in price like gold? Ha ha ha.

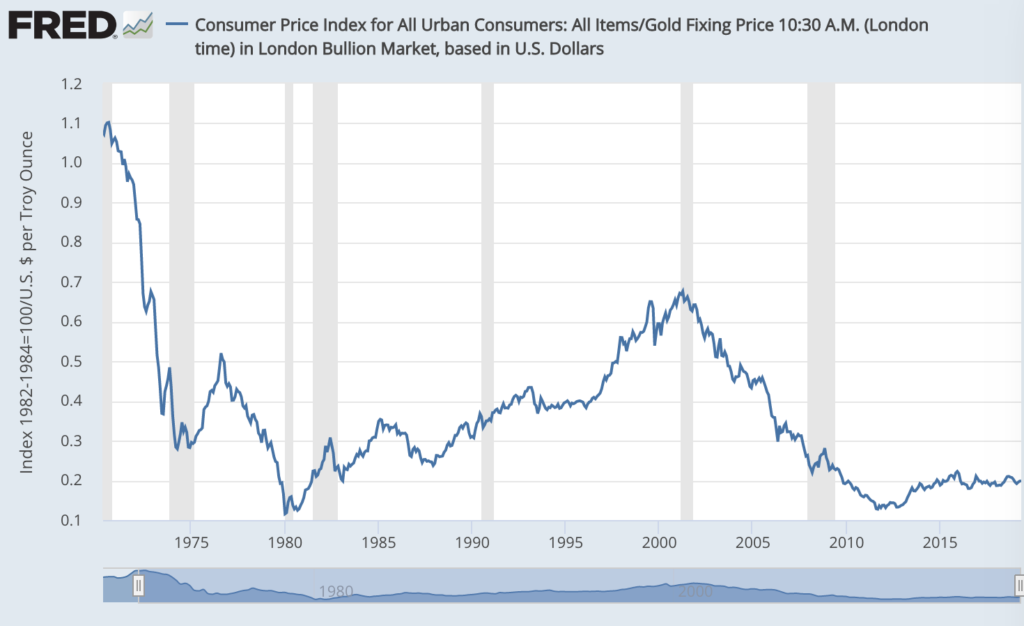

This graph shows the ratio of the CPI to gold prices, which is the price of goods in gold terms:

The deflations of the 1970s and the early 2000s are huge. Now in fairness the rise in gold’s value in the 1970s was mostly due to its use as an inflation hedge under fiat money. But the 2000s surge in the value of gold was more likely due to enormous growth in demand in developing countries, a real problem if you are using gold as money.

Lewis might argue that the US returning to gold would miraculously stabilize its value. Why, because some academics wrote a paper?

Ha ha ha.

In fact, to have any chance of stabilizing the value of gold it’s not enough for one country to adopt it as its standard, you’d need to recreate an international gold standard. So future Fed chair Judy Shelton will talk Mario Draghi and Xi Jinping into adopting the gold standard?

Ha ha ha.

Then’s there’s the great deflation of 1929-33, which directly led to the worst depression ever and resulted in the Nazi’s taking power in Germany. Is this part of the “centuries” of real life success?

I know, that interwar gold standard was not “done correctly”; the government messed it up. So let me get this straight. We need a gold standard because the government will mess up fiat money. Under gold, the government will be disciplined, prevented from creating too much money. And then when the gold standard doesn’t work because the government was too disciplined, created too little money, it’s not the fault of the gold standard?

Ha ha ha.

Some will argue that the interwar gold standard wasn’t the real thing, and that only the pre-1914 “classical” gold standard counts. But Lewis goes the other direction, even the pathetically weak post-WWII regime counts as a gold standard in his book:

Stable Money advocates still favor a gold-standard system – the proven method that served as the foundation for prosperity in the U.S. and around the world for nearly two centuries before being abandoned, after two wonderfully prosperous decades, in 1971.

Wait. The inflationary monetary policy under LBJ and Nixon was an example of the success of the gold standard?

Ha ha ha.

Lewis doesn’t seem to realize that even the quasi-gold standard of the post-WWII era was entirely abandoned in March 1968, when market price of gold was no longer pegged at $35/oz. Yes, the official price peg at $35/oz continued until 1971, but that’s meaningless. Indeed last time I looked the official price was still $42.22/oz. So by Lewis’s logic we are still on the “gold standard”.

Ha ha ha.

In fact, while there was a very weak gold standard up until 1968, the gold standard of 1929-33 was far more orthodox, albeit not as orthodox as before 1914. So if Lewis is going to claim the “gold standard” somehow created the post-WWII boom, he’s got to also own the Great Contraction of 1929-33.

Ha ha ha.

My point is not that there aren’t respectable academics advocating a gold standard. But those who do so certainly aren’t advocating the “gold standard” in effect until 1968, much less 1971. Rather they favor a highly decentralized regime where free banks would create private banknotes that are backed by gold. Bretton Woods was a government run system, and the Great Inflation began while it was still in effect.

And why isn’t Lewis worried that “market manipulation” will disrupt the gold market just as he thinks it would disrupt the NGDP futures market? I know, it’s pretty far fetched to believe that someone could manipulate the global market for important precious metal. Oh wait . . .

Silver Thursday: How Two Wealthy Traders Cornered The Market

Ha ha ha!

Now let’s go back to Lewis’s worry about market manipulation under an NGDP targeting regime. Market manipulation only make sense if you are going to extract profits from someone. But at who’s expense will NGDP market manipulators profit from? Not the Fed; I’ve advocated that they avoid taking a net long or short position. Not taxpayers. Not my 93-year old mom, she won’t trade the contracts. So are we to believe that a bunch of Wall Street firms will extract big profits from “manipulating” the NGDP futures market (or other markets in side bets) at the expense of other big Wall Street firms who passively sit back and get taken advantage of?

I actually hope someone manipulates the NGDP market. Then I can get rich taking the opposite bet. After all, market NGDP manipulation requires taking unprofitable bets in one market (NGDP futures) to earn gains in side bets in another. So let’s play!

Seriously, I know I won’t win this argument, which is why I now favor using NGDP contracts as merely a “guardrail”, where the Fed could ignore any attempts at market manipulation. I don’t think this is needed. My original plan would work fine, as no trader could do enough market manipulation to materially impact the path of NGDP. But a guardrails approach is a reasonable compromise if it will reassure people frightened of markets, people like Lewis.

HT: Sam Bell