Why so negative?

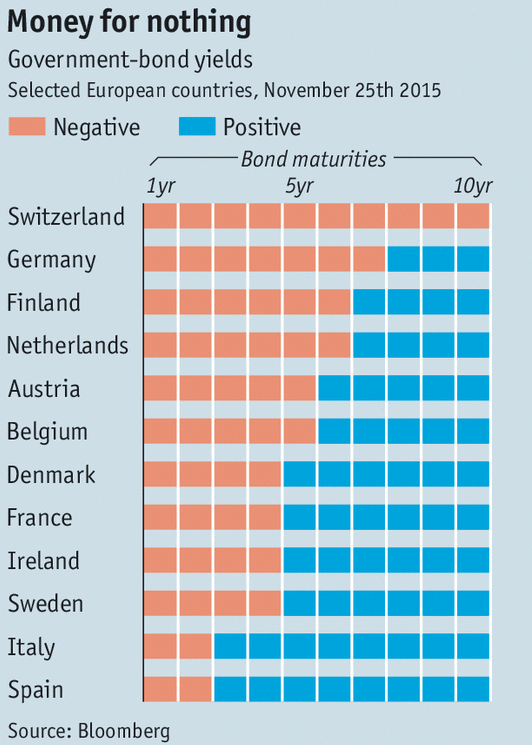

Here’s an interesting graph in The Economist, showing the extent of negative interest rates, by country and by maturity:

Not only are interest rates negative on 10-year Swiss government bonds, they are significantly negative, minus 41 basis points according to the FT. Here are some observations:

Not only are interest rates negative on 10-year Swiss government bonds, they are significantly negative, minus 41 basis points according to the FT. Here are some observations:

1. The differences within the eurozone mostly reflect default risk. But notice that despite the default risk, even Spain and Italy have lower government bond yields than the US.

2. The differences between the eurozone (especially Germany) and Switzerland relate to expected exchange rate changes. The Swiss franc is expected to gradually appreciate against the euro. Why is that? Perhaps because the Swiss National Bank (SNB) has pursued contractionary policies in the past, especially when it (foolishly) allowed the SF to sharply appreciate at the beginning of the year. Traders naturally expect more of the same. The Danes sensibly kept their currency pegged to the euro.

3. OK, but then why are eurozone rates lower than in the US? The euro has recently depreciated. Here you need to distinguish between levels and rates of change. (And this is something that lots of people miss.) An expansionary monetary policy can be thought of as reducing the value of the currency, or reducing the expected growth rate in the value over time (or both). But those are actually two radically different kinds of expansionary policy. The recent ECB policy has resulted in a one-time reduction in the value of the euro, but from this point forward it is expected to appreciate against the US dollar. Why? Probably because the ECB’s inflation target is a little lower than the Fed’s inflation target, although low eurozone rates may also be related to ECB credibility problems.

4. As far as the low level of interest rates in all developed economies, I attribute that partly to slow NGDP growth, but there also have to be other factors involved. And always remember that a low interest rate is not a monetary policy, it might reflect either easy money (liquidity effect) or tight money (NeoFisherian view.) Keynesians and NeoFisherians both make a mistake in assuming that a low interest rate policy can deliver some sort of desired result. (Oddly they make exactly opposite errors on what sort of results.) Low rates are not a policy.

5. Tyler Cowen linked to Matt Rognlie’s research papers. (Any top university not making him a job offer should have their head examined.) He has a paper on the zero bound that is full of interesting stuff. I particularly liked the analysis of the welfare costs of negative interest. Friedman showed that positive interest rates were a tax on money, and hence inefficient, but I had never given much thought to the costs of a subsidy on currency use. Rognlie also notes (correctly in my view) that before currency is withdrawn from circulation the government should first withdraw high denomination notes.

6. Although most have us have been surprised that currency demand near the zero bound is less elastic than we expected, I still think it might be more elastic in the long run than in the short run, due to the cost of adjusting currency stocks. I’d note that US currency demand seems to be moving upward with a lag, after short term rates fell close to zero in late 2008. On the other hand the negative 41 basis point yield on long-term Swiss bonds suggests that investors expect the SNB to maintain significantly negative rates for an extended period of time. So even in the long run, demand can’t be perfectly elastic at the zero bound. I recall reading that the SNB was informally discouraging currency use, by telling banks not to pay out large sums of currency to depositors. (Unfortunately I forgot where I read that.) Of course the US government has been trying to criminalize the use of significant sums of currency.

7. The Economist article has some interesting speculation on the future of currency at the zero bound:

As interest rates creep further into the red, economists’ prescriptions have become bolder. In a speech in September Andy Haldane, the chief economist of the Bank of England, outlined a range of options to allow rates to go lower still. The most radical would be to get rid of the mattress option by abolishing cash altogether. Ken Rogoff of Harvard University calculates that there is $4,000 of currency in circulation for every person in America. Much of it is used to hide transactions from tax authorities or the police. Abolishing it would curb such activities, as well as helping central bankers.

Yet depositors might still find ways to safeguard their savings. Switching to foreign currency or precious metals would be an obvious option. As Kenneth Garbade and Jamie McAndrews of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York point out, taxpayers could make advance payments to the taxman and subsequently claim them back. Depositors could withdraw funds in the form of bankers’ drafts (certified cheques) to use as a store of value. Such drafts might even become a form of parallel currency, since they are transferable. Any form of pre-paid card, such as urban-transport passes, gift vouchers or mobile-phone SIMs could double up as zero-yielding assets. If interest rates became deeply negative, it would turn business conventions upside down. Companies would seek to make payments quickly and receive them slowly. Their inventories would grow fatter.

Note that even if depositors found a way to avoid sharply negative interest rates after the abolition of currency (say by holding foreign currency, or pre-paying taxes), the central bank could still use negative rates to reduce the demand for bank reserves (make it a hot potato), and hence boost NGDP. But as always they need to be aware of where the Wicksellian rate is, and not just chase the Wicksellian rate lower in a futile attempt to jump-start NGDP growth. They need to get ahead of the curve.

BTW, I strongly oppose the abolition of cash. Like high taxes on cigarettes, it’s a highly regressive policy that seems to have support among progressives.

PS. Marcus Nunes sent me an excellent Jim Pethokoukis interview of Tino Sanandaji, discussing the Swedish economy. Lots of interesting info on Swedish history, the current immigration crisis, etc.