Many people have sent me an excellent new paper by Wolfgang LECHTHALER, Claire A. REICHER, and Mewael F. TESFASELASSIE, Kiel Institute for the World Economy. The front page notes that:

This document was requested by the European Parliament’s Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs.

However it clearly represents the authors’ views, and is not any sort of official statement by the EU.

As far as issues related to implementation are concerned, a strict inflation target can be simpler in certain ways to implement than either a flexible inflation target or a NGDP target, because revisions to the data on inflation are small, while revisions to the data on NGDP or real GDP are larger. Moreover there is considerable uncertainty about potential output growth. These are problems discussed in great detail by Orphanides and Williams (2002), Rudebusch (2002), and Goodhart et al. (2013). However, a counter-argument suggests that a NGDP target, even if in levels, would make it easier to avoid issues related to the measurement of the output gap. Additional arguments in favor of NGDP targeting involve the idea that it is easier to sell more stable nominal incomes to the public during bad times, and that a NGDP level target per se would increase the degree to which monetary policymakers are held accountable, by providing a measurable outcome.

To summarize, the theoretical evidence suggests that an explicit NGDP target, especially in levels, could possibly help the central bank to promote long-run price stability while allowing for a short-run response to output. However, this evidence is still relatively uncertain, and in the meantime, we find it useful to clarify the debate about what should and should not be expected to be achieved with a NGDP target.

I’m not qualified to discuss the data revision question, although Mark Sadowski challenged the conventional wisdom. I would make two points:

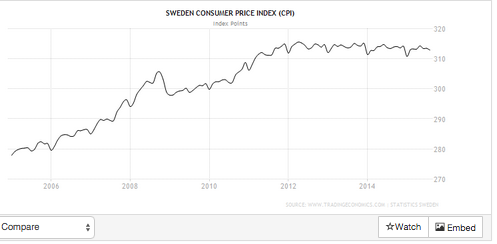

1. Even if measured inflation is not sharply revised, it remains a very inaccurate measure of the sort of price changes that have macroeconomic significance. For instance, a large share of the core CPI is based on rent and rental equivalents for housing. That data isn’t even a true “price”, and has no business influencing monetary policy. Last time I looked housing was 39% of the core CPI. This problem is briefly discussed later in their paper.

2. Revisions to NGDP are not large enough to be of macroeconomic significance, with one exception—changes in methodology. A recent example is the addition of R&D spending to investment, which caused a jump in NGDP. But there’s pretty general agreement that monetary policymakers would allow “base drift” in those cases; they’d raise the target by the amount of the upward bump from the new definition of NGDP. Also note that the Fed should be targeting expected NGDP 12 or 24 months out in the future, which makes near term data revisions much less important.

The theoretical case for NGDP level targeting as a forward guidance tool has been made, among others, by Woodford (2012). Similarly, in a recently published study, Coibion et al. (2012) have found strong theoretical support for price level targeting. Importantly, they take the zero lower bound into account, and they find that under inflation targeting, recessions that are deep enough so that the ZLB becomes binding are rare but costly. They Is nominal GDP targeting a suitable tool for the ECB’s monetary policy? They go on to show that price level targeting would result in less-deep recessions and stronger recoveries than would inflation targeting. Furthermore, price level targeting would imply that the ZLB would become binding less often. Therefore, switching from inflation targeting to price level targeting can lead to a substantial improvement in overall welfare, even if there is no foolproof way for such a target to always avoid hitting the zero lower bound. However, we are not yet aware of a study which compares price level targeting with NGDP level targeting, in light of the other theoretical considerations that we consider to be important. Therefore, we still consider the choice of a level target, were one to be adopted, to be an open question.

Someone should do that study!

In fact, this inability to use monetary policy to fine-tune prices or GDP motivates the debate about Taylor rules. Under a Taylor rule, the ECB would increase interest rates whenever inflation or output is above target. It turns out that something like a Taylor rule could also be used to implement NGDP targeting, at least when the zero lower bound does not bind. As Andolfatto (2013) shows, this would entail adding an additional term to represent the past deviation of the price level from its long-run path. While the specific implementation of this idea would require more thought, this idea would require relatively few changes from current operating procedures, to the extent that current policy resembles a Taylor rule but with equal weight on inflation and on output.

A more ambitious idea would be to set up a futures market in a price index or NGDP, and then for the central bank to either buy and sell these futures, or otherwise adjust monetary policy, in order to use these futures prices (rather than interest rates) as an operating instrument. To the extent that these futures prices represent accurate forecasts, then this approach should minimize fluctuations in the underlying target. Furthermore, this idea would encourage central banks to act proactively to avoid future target misses, rather than act reactively to past target misses. This idea is known as “market monetarism”, in the words of Christensen (2011) and Sumner (2011). While this approach is innovative, the likely consequences of this policy approach are not yet completely clear, and this approach would require the euro area to set up a new array of futures markets. In fact, for these futures markets to make it possible to target NGDP, financial markets would have to be efficient, in the sense of providing accurate forecasts. To the extent that financial markets are not efficient (because of bubbles, market frictions, or policy itself), then targeting futures prices would not completely solve the problems inherent in implementing a NGDP target. Nonetheless, if futures markets were to be set up, they would likely provide some information about the beliefs of market participants, and this information would be useful in implementing the target.

I’m glad they mentioned the usefulness of setting up these markets, even when they are not used as a policy instrument.

Market inefficiency is real, but very unlikely to be large enough to be of macroeconomic significance. And if I’m wrong at least there’s the silver lining that I’ll get rich trading the futures when the market price is clearly wrong.

Another issue is related to central bank communication. For instance, Sumner (2011) posits the following scenario. During a period of low inflation, an inflation target calls for higher inflation. However, higher inflation might be difficult to communicate to the public, because the public thinks of higher inflation something bad (i.e. a higher cost of living). In contrast, a NGDP target would call for increase in nominal income, and that might sound more acceptable to the broader public. This is because the public thinks of higher income as something good. The opposite would be true when inflation is high. During a period of high inflation an inflation target calls for lower inflation (which sounds good to the public). In contrast, a NGDP target would call for lower nominal income (which sounds bad to the public). In any case, policymakers who wish to implement an inflation target or a NGDP target would have to think about how they communicate these targets to the public.

Here I add that NGDP communicates more clearly all the time, both when easing and tightening. The public doesn’t understand the distinction between supply and demand side inflation. But the authors are correct that the NGDP language would be more popular when the central bank is trying to stimulate. Of course due to the zero bound problem it is precisely those times when clearer communication is most needed. When central banks want to tighten they face no zero bound problem, and hence communication is less important.

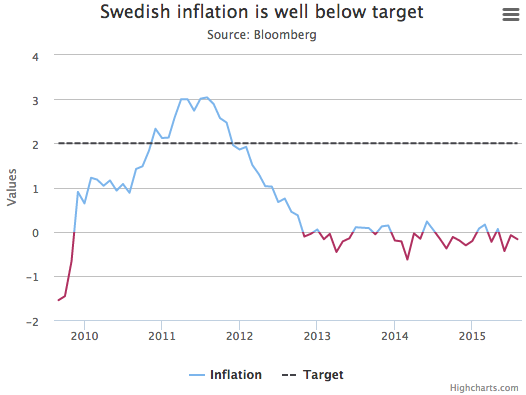

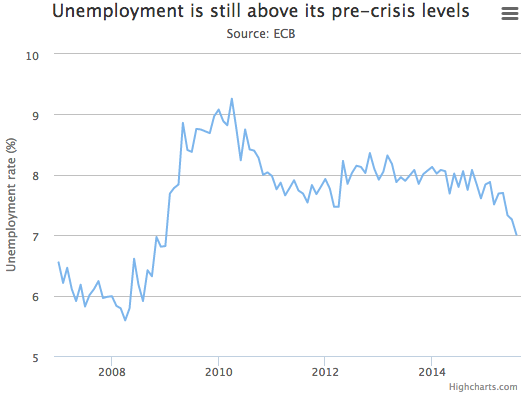

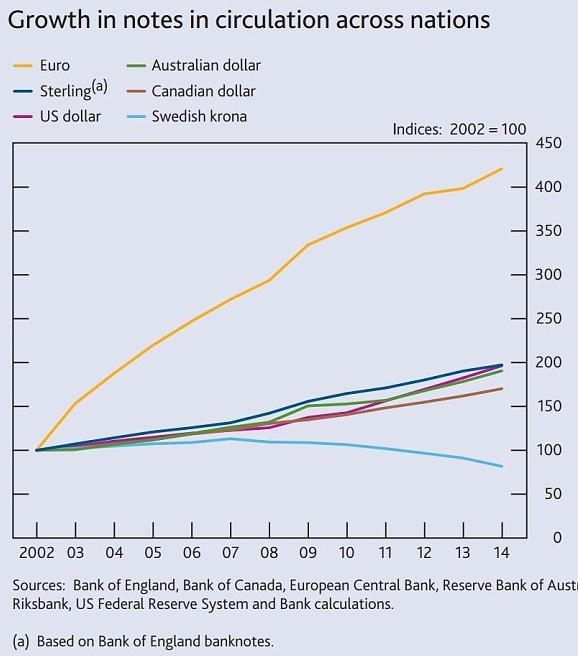

Read the whole paper, it’s an outstanding survey of the topic, and I’m glad to see that people in Europe are paying attention to this issue. The current ECB policy regime is clearly not effective in meeting the macroeconomic policy goals of the EU, low and stable inflation plus economic stability.