Moral hazard: If you are not taking socially excessive risks, you aren’t doing your job

Tyler Cowen recently quoted from a paper by Cheng, Raina and Xiong (in the AER) on the banking crisis:

We analyze whether mid-level managers in securitized finance were aware of a large-scale housing bubble and a looming crisis in 2004-2006 using their personal home transaction data. We find that the average person in our sample neither timed the market nor were cautious in their home transactions, and did not exhibit awareness of problems in overall housing markets. Certain groups of securitization agents were particularly aggressive in increasing their exposure to housing during this period, suggesting the need to expand the incentives-based view of the crisis to incorporate a role for beliefs.

The title of Tyler’s post is:

Further evidence that the housing crisis is about screwy beliefs, not moral hazard

But why not both? And indeed why not 75% moral hazard and 25% screwy beliefs? What does the “moral hazard is to blame” hypothesis actually claim?

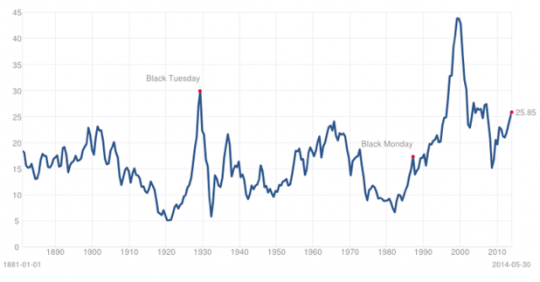

One thing it does NOT claim is that moral hazard caused bankers to begin taking excessive risks in the early 2000s. Rather the claim is that with moral hazard bankers would always take excessive risks, and that they got a “bad draw” around 2006-09. Thus without FDIC, banks might target a loan portfolio with risk X, and with FDIC and TBTF they might target a loan portfolio with risk factor 3X. But even with FDIC and TBTF, the subjective probability that the typical bank’s loan portfolio will lead to bankruptcy will be rather low.

It seems like all I write about these days is cognitive illusions. When the once in a century bad draw occurs, it will be tempting to focus on the specifics of that event, and not the underlying regulatory regime that leads to this size disaster occurring once a century, instead of once a millennia. And then of course there is also the issue of unstable monetary policy, which makes these black swans somewhat more frequent. It will also be overlooked.

I am not saying there weren’t lots of screwy forecasts—as I indicated the bankers did make some poor choices (underestimating black swans) and deserve some of the blame for the crisis. As do all the government regulators that encouraged them. BTW, I am indebted to Neil Wallace for the observation that a banker is not doing his job unless he is taking socially undesirable risks.

The irony here is that while the government should be encouraging less risk taking (I defer to John Cochrane on the best methods) they were encouraging even more excessive risk taking than the bankers actually took. It would be like giving your teenage son the keys to the car, and then topping it off with a gift certificate to buy beer.

PS. Of course “cognitive illusion” is an easy charge to throw around. Let it be noted that while I consider myself above average at avoiding them, Tyler Cowen is a world class avoider of cognitive illusions. So keep that in mind when evaluating who is right in this case.

Traveling today–comments may be delayed.