Today I’ll link to some other interesting posts:

1. Market monetarism is not haram

Left Outside has a fascinating post on Iranian monetary policy and the Islamic prohibition on “interest.” Because I’d like to ban discussion of all the “I-words” (interest rates, income, inflation, etc.), his post made me slightly more sympathetic to the Islamic religion.

This is cool! [1] Hassan Rouhani talking about monetary policy? Could I be any more excited? No.

This is cool! [1] Hassan Rouhani talking about monetary policy? Could I be any more excited? No.

Despite inventing zero, arabs have no use for it, [2] at least not when it comes to central banking. Lending money at interest is haram in Islamic finance so the use of interest rates to control demand as is normal in the west doesn’t apply. So does this also means that unlike in the UK and the US there is no danger of interest rates going to zero and the economy entering the liquidity trap?

. . .

Sukuk is also an important concept too. This is similar to a bond in which interest is regularly paid on a principal. However, because riba is haram in Islam it cannot be structured like this. Instead sukuk imply a transfer of ownership and can look like a form of repurchase agreement. You agree to repurchase something at a certain price over a certain period of time. This echoes previous posts of mine of what saving really is. Interest rates are just symbolic, what is really happening is people buying durable things today with an expectation they will be able to sell them on for more in the future. Interest rates are our way of expressing that, Murabahah or Sukuk are another. The latter seems clearer and more honest on the mechanism actually.

(At this point, I do want to point out to all the snooty economists, engineers, mathematicians who mock post-modernism…who’s laughing now?)

. . .

As Lorenzo tells me, actually the Indians invented zero as a concept, the Arabs were miles behind. More here.

PS. When I said I wanted to ban all discussion of “income,” I was referring to the microeconomic concept that includes things like “capital gains,” which are not a part of “national income.”

2. Monetary offset

Yichuan Wang has a really nice Quartz piece on monetary offset. Here’s an excerpt:

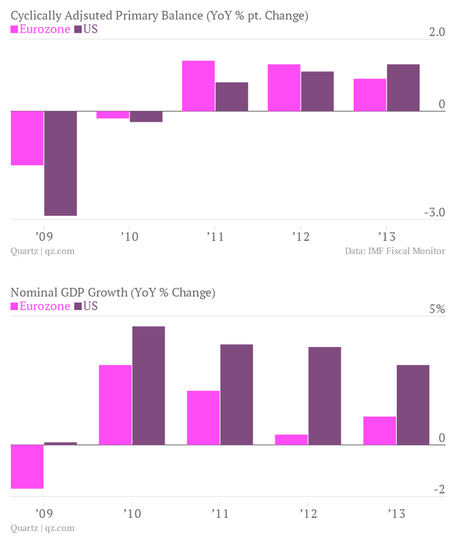

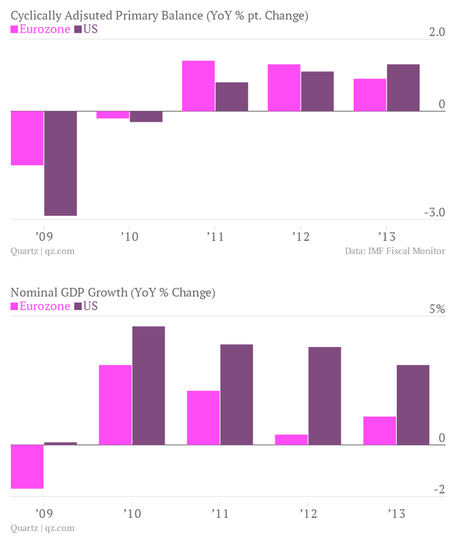

To get an idea of how bad it could have been, one need only look to the Euro zone. As measured by changes in Cyclically Adjusted Primary Balances, a measure of whether of government spending that adjusts for the business cycle, both the US and Europe have endured savage government austerity. Yet nominal GDP growth in the US has been steady while Europe’s has collapsed.

The biggest difference? Monetary policy. While the Fed been a proponent of holding down interest rates throughout the recovery, the European Central Bank actually raised rates in response to inflation fears in 2011, and just recently lowered its benchmark interest rates to 0.25%.

The biggest difference? Monetary policy. While the Fed been a proponent of holding down interest rates throughout the recovery, the European Central Bank actually raised rates in response to inflation fears in 2011, and just recently lowered its benchmark interest rates to 0.25%.

This experience has also shown that deleveraging isn’t a roadblock to monetary policy. From the peak of the crisis, the ratio of household liabilities to annual consumption fell around 26 percentage points from its peak of 1.44 in the second quarter of 2004. Theoretically, this should have meant that the drawdown in federal spending should have been a double whammy””both by directly lowering spending as well as hurting balance sheets. Yet the recovery barely budged, showing that even when people are paying down their debts, monetary policy can still help.This experience has also shown that deleveraging isn’t a roadblock to monetary policy. From the peak of the crisis, the ratio of household liabilities to annual consumption fell around 26 percentage points from its peak of 1.44 in the second quarter of 2004. Theoretically, this should have meant that the drawdown in federal spending should have been a double whammy””both by directly lowering spending as well as hurting balance sheets. Yet the recovery barely budged, showing that even when people are paying down their debts, monetary policy can still help.

3. Are the Obamacare cost controls “good deflation?”

Greg Ip has an interesting piece at Free Exchange:

Therefore, a decline in the price of health services may help consumers at the expense of producers. Ordinarily, this would not be a macroeconomic issue. But it is when inflation is already too low, in which case this deceleration in prices is potentially bad.

I say “potentially” because in some circumstances, lower prices are a net positive for the economy. For example, higher productivity would enable providers to lower prices with no loss of income. Obamacare contains many incentives to raise efficiency, such as penalizing hospitals for high readmission rates, but there’s little evidence productivity as a whole has risen enough to tip the overall trend. Most of Obamacare’s impact on spending has been through brute reduction in payments: to Medicare Advantage plans and to hospitals who treat Medicare patients. The Administration hopes providers will cope with lower payments by finding new efficiencies; but they may instead simply accept lower profit margins, though over time that could drive providers out of the market, reducing supply; or they may negotiate lower input costs. And since health care is labour intensive, that means wages.

At first glance he seems to be assuming that all deflation is demand-side deflation, and hence contractionary. On closer inspection he does draw a distinction between productivity improvements that leave NGDP unchanged and fiscal austerity that reduces Medicare/Medicaid reimbursement.

In my view this sort of reduction in transfers (lower reimbursements) is either a wash, or slightly expansionary. If the Fed targets NGDP then lower inflation means higher RGDP. If the Fed targets inflation then more aggregate supply is expansionary. The question is whether or not a reduction in Medicare reimbursements boosts AS. I.e., whether or not it is a nominal wage cut, when wages are sticky. I think so, but am not certain.

I am indebted to Michael Darda and Saturos for pointing me toward the issues raised by Greg Ip’s post.

4. Reading between the lines

When reading financial articles always try to think about what you are reading from a monetary policy/expectations perspective. Here’s a great example from the FT:

“The signal from the Federal Reserve is driving home the point that ‘tapering’ is not tightening,” says Marc Chandler, strategist at Brown Brothers Harriman. “This seems to imply a willingness to see curve steepening, where the long-end retreats some, but that the short-end does not bring forward a Fed Funds rate hike.”

Translation: Effective monetary stimulus will lead to higher long-term rates. The key is to make sure those long-term rate increases reflect the impact of policy on growth, and not monetary tightening. You do that by committing to hold short rates low for an extended period, or better yet until certain macro benchmarks are met.

As recently as late September, with benchmark 10-year US government bonds yielding 3 per cent, the Fed was forced to rule out a widely expected taper as financial conditions had tightened too much, pressuring housing and the economy. A key test is whether forward guidance can keep equities and other asset markets buoyant once the taper is imminent.

“Long-term yields are always central to any measure of financial conditions, but if the mix of other variables such as equities, front end yields and the dollar are behaving, then it’s less of an issue to see a higher 10-year yield,” says Mr Ruskin.

Translation: Effective monetary stimulus will lead to higher long-term rates. The key is to make sure those long-term rate increases reflect the growth impact of policy, and not monetary tightening. That’s why you focus on other asset markets like equities and forex rates. If equity prices are falling and the currency is strengthening, then the higher rates may reflect tighter money. As always, an NGDP futures market would be a HUGE help. The Fed’s failure to create and subsidize trading in a NGDP prediction market represents inexcusable laziness on their part.

5. Fed misinformation (no pun intended)

I strongly recommend everyone look at this video of George Selgin’s informative and highly entertaining demolition of Fed misinformation on the history of American banking. I also spoke at the same Cato event, but George was the star of the show.

6. All hail Mark Carney

Travis sent me the following:

Mark Carney is moving the Bank of England in a direction it hasn’t taken in more than six years.

The governor took steps yesterday to head off a potential housing bubble by diluting a credit-boosting program, two weeks after raising growth forecasts and signaling interest rates might increase sooner than previously projected.

. . .

Carney’s measures coincide with evidence that demand and prices are rising. Lenders granted 67,701 mortgages in October, the most since February 2008, the BOE said today. Home values increased 0.6 percent in November, Nationwide Building Society said. They climbed 6.5 percent from a year earlier, the fastest pace since July 2010.

For economists at HSBC Holdings Plc (HSBA) and ING Bank NV, the measures may allow the BOE to keep interest rates lower for longer. That’s because the action by its Financial Policy Committee shows it can use macro-prudential tools to target specific problems in the economy.

“Today’s report is not particularly hawkish,” said Simon Wells, an economist at HSBC in London. “The BOE wants to use new macro-prudential tools to calm the housing market, rather than deploy the blunt instrument of higher interest rates.”

Carney has said he won’t consider raising rates until there is sustainable economic growth. He said yesterday the housing curbs will help him keep that pledge.

That’s right, use monetary policy for NGDP and more targeted policies for housing distortions.

7. The wisdom of Paul Krugman

Simple doesn’t mean stupid. Thinking that it does, does.