Reasoning from multiple price changes

There’s been a lot of recent discussion about the disconnect between the stock and bond markets. Stocks are hitting records (suggesting strong growth ahead) while bond yields are falling (suggesting slow growth ahead.) I don’t have any definitive answers, but a few words of caution:

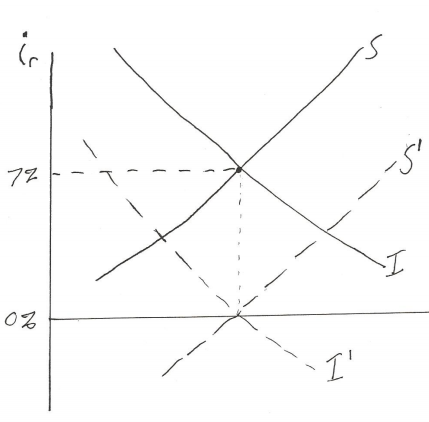

Many factors affect stocks and bonds, not just growth. Some of those factors affect the two markets in very different ways. For instance, suppose the investment schedule shifted to the left due to slower population growth, while the global saving schedule shifted to the right because of growing Asian prosperity. In that case global real interest rates might fall sharply:

Indeed this is pretty much what happened to real interest rates on 10 year Treasury bonds over the past 33 years. They have fallen from about 7% to about 0%. And yet saving and investment haven’t changed all that much as a share of GDP. Some of the recent drop was caused by weak economic growth, but the big drop from 1981 to 2007 cannot be explained by slower growth.

Now let’s suppose that real interest rates dropped for some reason unrelated to slowing economic growth. How would that affect the stock and bond markets? Stock prices would obviously rise, and bond yields would fall. Indeed this might even occur if expected real GDP growth slowed slightly. So while economic growth often causes stock prices and bond yields to move in the same direction, there are plenty of exceptions to this pattern. The current mix of high stock prices and low bond yields might be a bit unusual, but it’s hardly unprecedented. Even if the factors I cite are not correct, dozens of other factors might explain the paradox.

Some people have asked me about a paper by John Cochrane, which advocates making permanent the policy of a large Fed balance sheet combined with interest on reserves. I’d slightly prefer the old system of no IOR, but I don’t really have any strong objections to the policy. The real issue is what sort of policy target should the Fed have, and how should they achieve that target. I seem to recall that Cochrane likes my futures contract targeting proposal, but prefers a CPI target to a NGDP target.

Cochrane’s analysis is based on the “fiscal theory of the price level.” I think that theory makes sense for a place like Zimbabwe, but not the US. In the US it seems to me that the Fed is the dog and fiscal policymakers are the tail. The Fed determines NGDP growth, and the fiscal policymakers must live with that constraint.

I also believe that Cochrane exaggerates the impact of IOR:

However, interest on reserves, together with the spread of interest-paying electronic money, radically changes just about everything in conventional monetary policy analysis. Standard answers to fundamental questions like the determination of inflation, the ability of the Fed to control real and nominal interest rates, the channels of the effect of monetary policy especially on the banking system, and so forth all change dramatically in a regime of interest on reserves and large balance sheet. The Fed anticipates some, but not others. Old habits die hard, and clear thinking is needed to dispel them.

I guess I’m too old for clear thinking, because I don’t see how anything important changes. In the old days the Fed controlled the price level by controlling the supply of base money (through OMOs and discount loans) and influencing the demand for base money (by changes in reserve requirements.) Now they’ll have two tools for influencing base demand; RRs and IOR. The quantity theory still holds–a permanent doubling of the base will, other things equal, cause the price level to be twice as high as it would otherwise be. MV=PY will still be perfectly true each and every second, because it’s a DEFINITION. However (base) velocity will be far less stable. The velocity of the broader aggregates that the old monetarists care about would presumably be about the same.

Money will still be neutral in the long run, and short run non-neutralities will come from sticky wages and prices. Irving Fisher and even David Hume would have had no trouble understanding a world of IOR.

But it will become harder to teach monetary theory. Zero interest base money makes the “hot potato effect” really easy to explain.

Tags:

30. May 2014 at 07:48

“Money will still be neutral in the long run”

Money, inflation and ngdp all grow at different speeds historically disproving neutrality. Unless you assume constant velocity. Why assume velocity is constant if it never is?

30. May 2014 at 07:55

Excellent blogging. But I have a question: “Money will be neutral in the long run.” What about Japan? Seems to me the BoJ asphyxiated Japan for 20 years and the noose was still hampering growth until Abenomics. What is the long run?

If I formed a money-worshipping ascetic cult and gained control of the FOMC (I mean even worse than we have), with the plan to cut the money supply by two-thirds in the next 33 years, would the impact be neutral? I think I could stifle growth for decades.

And an economy retarded long enough…can the lost ground ever be recovered? Growth starts from a smaller base, even after the monetary policy is corrected…

30. May 2014 at 08:38

Rising stock prices and rising bond prices are expected with rising inflation of the money supply, due to the colloquial “too much money chasing too few [goods] securities.”

We just have to keep in mind that today’s expenditures are often financed by inflation of the money supply that occurred further back in time than what one might expect if one uses a constancy assumption of history having to repeat the same way with regards to timings and so forth.

I really don’t understand the fixation on rising bond prices being so strongly connected to deflation of the money supply specifically. Sure, paying lip service to the liquidity effect and so on helps, but it just seems like it is more of a hand waving or reluctancy than serious conviction.

The best way to think of bond prices, as a heuristic, is to think of falling bond prices and rising bond yields as generally taking place when consumer prices rise at the relative expense of bond prices, that is, when prior inflation works its way through the spending stream starting primarily in the financial markets, and then eventually hitting consumer goods prices, where by the time consumer goods prices are significantly affected, the inflation in the present has already been tightened, which puts downward pressure on bond prices and thus rising yields, and downward pressure on stock prices and fallong stock total returns. It is not a perfect interpretation, but it fits the facts fairly well, and it makes a lot of sense in theory.

The reverse of the above is likely what is happening to stock and bond prices now, with an additional time lag between inflation of the money supply, and stock and bond prices, but not yet enough time to significantly affect consumer goods prices. At this stage, significantly high expenditures on stocks and bonds relative to consumer goods, has made both stocks and bonds rise in prices.

If expenditures on consumer goods was higher than it was now, then it would be reasonable to expect rising bond yields and falling bond prices. But bonds are effectively being chosen more over consumer goods, which is why the “inflation premium” is relatively low.

Imagine the banking and financial industry having been nuked into a gigantic crater as per 2008. An incredible amount of dirt and concrete (inflation) could be poured into the crater, without significantly affecting the “average altitude” of the whole landscape (consumer prices). It should not be all that surprising to see the prices of bank oriented dirt and concrete (stock and bond prices) rise quite a lot, while the prices of average landscape oriented dirt and concrete (consumer prices) are rising only modestly at this time.

30. May 2014 at 08:42

“Money will still be neutral in the long run, and short run non-neutralities will come from sticky wages and prices.”

Money is never neutral. A neutral money is a contradiction in terms.

Money is not neutral in the long run because the long run is the effect of prior short runs, and if we are willing to accept that money is non-neutral in the short run, then we have already argued that money is not long term neutral either.

In short, it is impossible to make a neutral thing with only non-neutral parts.

30. May 2014 at 08:52

If money were produced in a free market since 1913, the world today would be very different than what it is. All the past inflation that benefited governments would not have taken place.

And no, it is not a valid reply to say that this is a fiscal issue, not a monetary issue per se. The reason it isn’t valid is because it would just be ignoring that even if the fiscal lanscape were different, than THAT landscape would have been shaped by non-neutral money in a different way. To not be a part of fiscal policy per se does not mean money is no longer neutral. We would just see how that world would be shaped by non-neutral money, and we can imagine people saying there too that money is long term neutral and that someone who says otherwise is really talking about X policy and not money per se.

Yet even if no laws at all existed, the effects of how money is produced, where, in what quantity, and how it is valued, and utilized in exchanges, would still shape what the world looks like at any given time, short and long run.

The reason this is often misunderstood is because it requires a lot of counter-factual reasoning, to have an active imagination of completely different worlds than what is observable. With so much datf driven focus in government bureaus, economists have unfortunately become mostly too dull witted and shallow.

30. May 2014 at 09:00

Benjamin:

“Seems to me the BoJ asphyxiated Japan for 20 years and the noose was still hampering growth until Abenomics. ”

Japan is worse off today than they were before “Abenomics”. All you’re doing is telling your beliefs about inflation.

30. May 2014 at 09:03

Danny, You said:

“Money, inflation and ngdp all grow at different speeds historically disproving neutrality.”

You’ll have to explain that one to me. What does the relative growth rates of money and prices have to do with money neutrality?

Ben, That’s a tougher question: is money superneutral? It’s possible that at very low money growth rates you can permanently depress output.

30. May 2014 at 09:15

Professor,

Danny’s statement seems to contradict the table you show in part 3 of your “Short intro course on money” series (and in your class):

http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=20216

MB growth and inflation track very well, especially as the rate increases.

30. May 2014 at 09:18

Oh look, Major_Moron is at it again.

Funny thing is, he doesn’t actually believe his own nonsense.

If he did, he wouldn’t be wasting time on the internet – he’d be sprinting to the nearest ATM to get to the money before someone else does.

Japan is worse off today than they were before “Abenomics”.

Got proof for that, imbecile ?

30. May 2014 at 09:30

If you compare MB growth to prices in places like Aus or US the result doesn’t support neutrality. Why is a country like Argentina credible as a data source? If money is neutral then why do many countries show non neutrality? The concept is pretty worthless and misleading IMO.

People sometimes assume money is neutral if velocity doesn’t change but velocity always changes so why assume constant velocity.

30. May 2014 at 09:32

“What does the relative growth rates of money and prices have to do with money neutrality?”

Neutrality says that they grow at same rate in long run. If the data doesn’t show this then its wrong right?

30. May 2014 at 09:44

Danny said:

“If you compare MB growth to prices in places like Aus or US the result doesn’t support neutrality. Why is a country like Argentina credible as a data source? If money is neutral then why do many countries show non neutrality? The concept is pretty worthless and misleading IMO.”

I linked to part 3 of Sumner’s “Short intro” series. In part 4 he answers your question:

“1. The eyeball test suggests the Quantity Theory of Money (QTM) works dramatically better for high inflation countries than low inflation countries. (Also true of PPP and the Fisher effect, for much the same reason.) In fact, money growth affects prices in all countries, but other factors are relatively more important when inflation is low. Let’s suppose that the gap between money growth and inflation does not vary with the average rate of money growth. For instance, suppose the gap is 3% on average, when examining very long run data. In that cases the gap will seem almost trivial when money growth rates become very large, say more than 30%/year.”

Link here: http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=20323

30. May 2014 at 09:45

“Got proof for that?”

Violence!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

30. May 2014 at 09:54

” In fact, money growth affects prices in all countries, but other factors are relatively more important when inflation is low. Let’s suppose that the gap between money growth and inflation does not vary with the average rate of money growth. For instance, suppose the gap is 3% on average, when examining very long run data. In that cases the gap will seem almost trivial when money growth rates become very large, say more than 30%/year”

So therefore even if money neutrality is true it is mostly irrelevant to the US with its current economic predicament.

30. May 2014 at 09:58

Thanks for the thoughts. The way equity investors (financial types) might think of it is that the risk free rate as dropped, lowering the cost of capital (the risk free part), making equities more valuable. It is a sort of nirvana for equity investors.

I had thought you might be more worried about the economy’s capacity to absorb shocks when ngdp is running so low, as implied by the low bond yields. Such a worry might raise the risk premium required to hold equities, as expected volatility should rise. But I recall I have raised that issue before and you are not too concerned.

30. May 2014 at 10:17

Daniel:

As expected, you are clueless about banking as well.

Withdrawing cash from your checking or savings account is not a creation of new “first reciever” money. It is a simple tranfer of money from one form to another. You would already have to be in receipt of money prior before you can withdraw cash from an ATM.

Money is created when the Fed engages in OMOs, or when a member bank expands credit. Money is not created when you convert your demand deposit account into cash.

As for Abenomics, I am not sure what you are asking for. I see the word “imbecile”, which suggests you’re still only interested in showing your immaturity. Again, not really interested in that.

30. May 2014 at 10:23

Playing political games with the remuneration rate is just like providing the more regulated DFIs with higher Reg. Q ceilings than the NBs (the risk takers). In the event of an up tick in the trend of inflation, it will induce dis-intermediation among just the NBs – lowering real-output.

Nominal and real interest rates will in the longer run increase as deficit spending requirements will be forced higher & higher (by the non-use of savings). And the interest recaptured by the Treasury will be wiped out by the interest expense paid to prevent the CBs from lending/investing (via the Fed’s new credit control device).

30. May 2014 at 10:23

“What does the relative growth rates of money and prices have to do with money neutrality?”

This is another argument showing money is not neutral.

Since relative money growth and prices have relative real effects, money therefor has non-neutral effects.

It is the Cantillon Effect in action.

30. May 2014 at 10:28

Philippe:

“”Got proof for that?”

Violence!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!”

In this case it is one effect of the result of violence replacing another, where the coercion is resulting in more wealth and purchasing power transfer both internally and externally.

30. May 2014 at 10:35

If there was a “wealth effect” generated by higher stock prices, then instead of a Great-Depression, there would have been a Great-Renaissance. The incentives to buy stocks are perverse.

It’s no surprise that the Fed can suppress all interest rates by simultaneously taking large volumes of debt off the secondary markets (reducing the demand for loan-funds), & then depressing economic activity by impounding savings within the CB system.

30. May 2014 at 10:40

Danny said,

“So therefore even if money neutrality is true it is mostly irrelevant to the US with its current economic predicament.”

I keep linking you to posts on Sumner’s “Short intro” series because I think you should read the full thing, but it’s clear you’re not getting the hint. The very next part of the series (part 5) talks about expectations, which explains why your statement is incorrect.

30. May 2014 at 11:45

Off-topic.

Prof. Sumner,

In 2005, 2006 and 2007, why did smaller banks generally make riskier loans than the big banks? We know about moral hazard as a result of the FDIC. But what factors kept the behavior of the big banks in check relative to the smaller banks?

30. May 2014 at 11:54

Predictably, Major_Moron is too retarded to follow his own theories to their conclusion.

Like I say to all austro-cultists – the day I’ll take you seriously is the day you sprint to ATMs to get to the money first.

Also, you failed to provide any proof that Abenomics made Japan worse off. Typical imbecility.

30. May 2014 at 11:54

Does this really indicate an uptrend or is it a one-month outlier?

“PCE Inflation Is On The Rise”

http://www.businessinsider.com/core-pce-is-rising-2014-5

30. May 2014 at 12:06

Daniel:

Completely not surprisingly, you are still completely clueless even after being shown that no new money is created when you CONVERT your existing ownership of checking account dollars, to cash bills instead which decreases your checking account dollars.

Sorry Daniel, but you are too intellectually inferior to have a coherent and informed debate with me.

And regarding Abenomics, you are still using the root word “imbecile”, which shows you are still more interested in showing your immaturity than you are with truth.

You got nothing you creep. At least you stopped demanding to see my photo.

30. May 2014 at 12:13

Well, if you were indeed the paragon of manliness you claim to be, you’d have shown off by now.

You evasion only proves my point.

Also – maybe there’s an ATM you need to run to.

30. May 2014 at 12:29

Daniel:

“Well, if you were indeed the paragon of manliness you claim to be, you’d have shown off by now.”

That doesn’t follow. I mean, you have shown yourself to be intellectually vapid, but that doesn’t imply you have to show me a scanned image of your highest academic achievement of a GED from that school run by your related parents.

“You evasion only proves my point.”

Evasion of what? Your immaturity?

“Also – maybe there’s an ATM you need to run to.”

Why? I would not be benefitting from any initial receipt of money. It would just be a conversion of existing money from one form to another.

30. May 2014 at 13:38

Scott Sumner (or all): We talk about small growth in the money supply cramping real output, but what about shrinking the money supply? The Divisia measure shows money supply now stagnant (Center for Financial Stability).

Maybe the Fed is experimenting with monetary anorexia….

30. May 2014 at 16:22

Guys,

The fact that most of the jobs created in this pathetically weak recovery here in the u.s. are low wage jobs…. thats wage flexibility and the “long run” in action.

Also, dannyb2b. I think your are confusing expectations of the future growth rate of the money supply versus actual impacts. If the Fed rigidly and transparently keeps to its forward guidance and stabilizes NGDP, (which stabilizes velocity by the way) than money can be neutral.

30. May 2014 at 17:51

Edward:

“The fact that most of the jobs created in this pathetically weak recovery here in the u.s. are low wage jobs…. thats wage flexibility and the “long run” in action.”

Please understand the difference between nominal and real wages.

Wages are a business cost. Lower wage rates means lower costs and output prices can be lower.

If business is sluggish, demanding that business costs increase isn’t a solution.

30. May 2014 at 17:53

Benjamin:

“Maybe the Fed is experimenting with monetary anorexia”

After pigging out at the all you can eat buffet for the better part of 5 years, any modest diet will feel like a dinner at Ghandi’s place.

30. May 2014 at 18:10

“Please understand the difference between nominal and real wages.

Wages are a business cost. Lower wage rates means lower costs and output prices can be lower.

If business is sluggish, demanding that business costs increase isn’t a solution.”

?????????????

30. May 2014 at 18:11

Prices arent falling in the US

30. May 2014 at 18:15

Edward:

Prices in the US are lower than they otherwise would have been with higher wages, and businesses would have had less money to purchase capital goods, which are the foundation of real wages.

30. May 2014 at 21:54

Garret and Scott

If money neutrality means that prices and permanent MB growth are correlated to some degree most of the time then I agree. If neutrality means 1 for 1 movements in prices and MB in the long run I dont.

The data for high inflation countries for about a 30 year period shows mb and prices moved closely in long run. But other countries not really. What about other periods?

Expectations can make Mb move at different rate to prices in long run according to part 5. How do we know exactly what caused prices to move closely for the high inflation countries in that specific period? maybe it was a coincidence.

Or maybe Im being bit closed minded and the truth is more like sometimes money is neutral and sometimes it isnt.

“Unfortunately the role of expectations makes monetary economics much more complex, potentially introducing an “indeterminacy problem,” or what might better be called “solution multiplicity.” A number of different future paths for the money supply can be associated with any given price level.”

Or maybe money just isnt neutral.

31. May 2014 at 00:48

dannyb2b

“If money neutrality means that prices and permanent MB growth are correlated to some degree most of the time then I agree. ”

Thats what it means

The data for high inflation countries for about a 30 year period shows mb and prices moved closely in long run. But other countries not really. What about other periods?

Not really? The data from the U.S. from 1982-2007 shows a strong (though not perfect correlation) betweem the MB and the price level

“Expectations can make Mb move at different rate to prices in long run according to part 5. How do we know exactly what caused prices to move closely for the high inflation countries in that specific period? maybe it was a coincidence.

When it comes to this it can be rightly said: Not really! Because we see the hot potato effect of high velocity in very high inflation countries like Brazil in the 1990’s

“Or maybe Im being bit closed minded and the truth is more like sometimes money is neutral and sometimes it isnt.”

Nope. Money is always neutral when expectations about its future growth path are crystal clear.

Why are you so determined to deny an obvious truth?

31. May 2014 at 01:11

“Money is always neutral when expectations about its future growth path are crystal clear.”

the growth path of money is different to the growth path of NGDP.

31. May 2014 at 01:26

Edward

“Thats what it means”

The word neutral should imply prices and money grow equally in long run otherwise the term is misleading.

“Not really? The data from the U.S. from 1982-2007 shows a strong (though not perfect correlation) betweem the MB and the price level”

Your cherry picking. Neutrality should show everywhere in time. Not just some periods and not others.

“When it comes to this it can be rightly said: Not really! Because we see the hot potato effect of high velocity in very high inflation countries like Brazil in the 1990″²s”

Expectations are in part formed by the MB growth but also in part other things. So the higher velocity may be due to other non MB factors as well.

“Nope. Money is always neutral when expectations about its future growth path are crystal clear.”

How do you know this?

“Why are you so determined to deny an obvious truth?”

Why do you easily resort to adhominems when someone has a different opinion?

31. May 2014 at 05:04

Thanks Garrett.

Danny, You said:

“Neutrality says that they grow at same rate in long run. If the data doesn’t show this then its wrong right?”

No, you are confusing money neutrality with the quantity theory of money. Money neutrality merely says that changes in the nominal supply of money have no long run impact on the real quantity of money. The QTM says M and P are correlated. For instance, under an inflation targeting regime the QTM doesn’t hold (no correlation) but money neutrality still holds.

James, I do worry about excessive low NGDP growth, but I don’t think nominal interest rates are the best indicator of that growth rate. They are definitely correlated, but not perfectly.

Travis, FDIC probably has a bigger impact on smaller banks, because there is a greater probability that FDIC will absorb the cost of bad loans.

31. May 2014 at 06:02

ssumner

“”Neutrality says that they grow at same rate in long run. If the data doesn’t show this then its wrong right?”

No, you are confusing money neutrality with the quantity theory of money. Money neutrality merely says that changes in the nominal supply of money have no long run impact on the real quantity of money. ”

Thats what I said I think.

2. June 2014 at 07:48

Danny, No, you said money neutrality implies M and P should grow at the same rate, which is not the prediction of money neutrality. That’s a prediction of the QTM.